Low-tech for low vision

Christchurch optometrist John Veale looks beyond the hype of high technology, presenting low-tech solutions to some of the challenges of low vision.

A simple first step to ensure a low vision patient feels supported and reassured from the outset, is to insist they attend their first appointment with their spouse, a family member or supportive friend. That way, both can hear everything first-hand, they can ask questions and compare notes afterwards.

Although a patient may have already been referred to an eye specialist and had numerous treatments for their condition, I still always ask, “Do you know what’s wrong with your eyes?” The answer is usually something like, “Sort of.” To explain using medical terminology would be unhelpful. “You have neovascular membrane,” would generally mean very little to the patient and could sound frightening.

Keep it simple

One way to establish a good rapport is to explain the vision loss in very simple terms. Many people only think that we see with our eyes, but I like to remind them that the eyes are our cameras and we actually see with our brains.

In macular degenerative cases, I hold up my fingers and ask the patient to imagine they are cells and that seven million of them, when hit by light, send signals down the optic nerve to the brain. I differentiate wet and dry macular degeneration by explaining the hardening of the capillaries can cause either a leak from the blood vessel, causing wet MD, or that a cell not getting the nutrients it needs causes dry MD.

To give patients and their partners a concept of macular size, I ask them to make a fist and hold their arm straight out in front on them. I explain that if the macular was completely gone, the side vision would remain, but the central vision would be a blurry patch, the size of the fist. This can be very reassuring.

Another reassuring tip for older patients, is to use Halberg Clips over their present spectacles to add and subtract power when reviewing and refining refraction, as being behind a phoropter can sometimes be disconcerting.

Low-tech solutions at home

Many people do not understand the importance of task lighting. I demonstrate this with a spot-lit near chart and an unlit one. I tell stories about my father, who had MD. When he couldn’t see the eyes in the potatoes he was peeling, I bought him a small black lamp with a goose neck for his kitchen bench - problem solved. When he said he couldn’t see the individual peas on his dinner plate, we got him another lamp - another problem solved. A strong torch is also a very useful item to have on the kitchen bench, to use when searching in cupboards.

When people complain they can’t see captions or subtitles on their TV, I ask them to perform the Pace Test. I bring a hand-held test chart slowly towards them, ending up a metre and a half away. The patient may be able to see down to the last three lines. I ask the person to stand up when viewing the TV at home and move one pace forward, then a further pace and so on until they can see the captions. That’s clearly the best distance for them to view the TV from. I then ask them to move a few paces to the left, then a few to the right and see if the TV is clearer to the side rather than directly in front.

Another piece of advice for the home is to leave power plugs in the wall socket and turn off at the switch. When your sight is low, it can be very difficult to put a plug into a socket.

Low-tech in the clinic

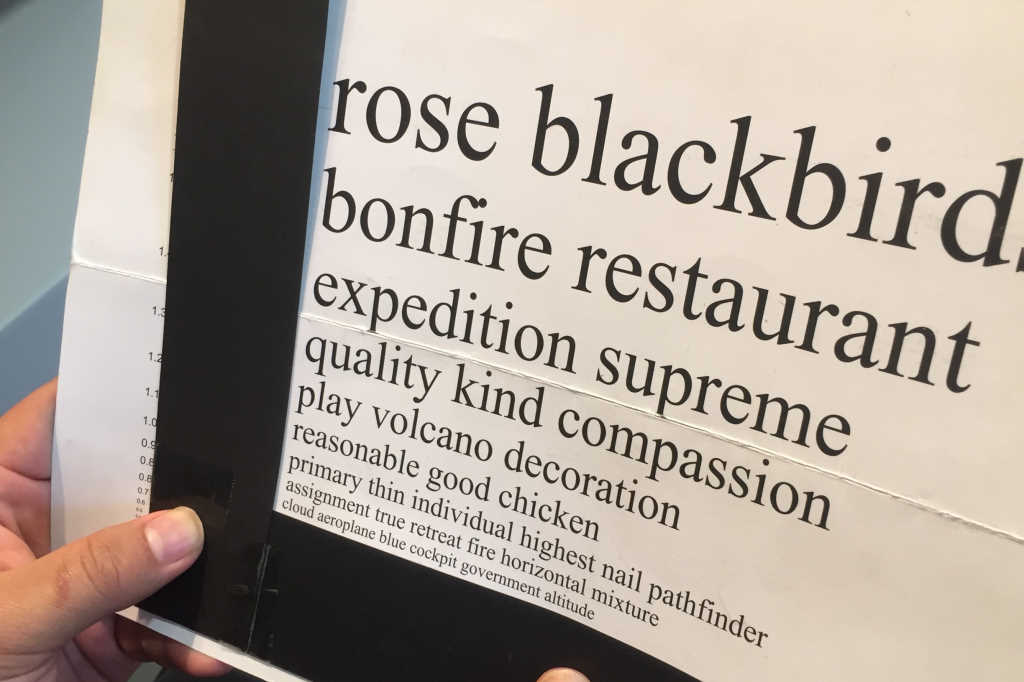

For field loss, I use an L-shaped black strip (see photo) for left field loss and invert it to create a backwards L for right field loss. I find using black strips along a line of numbers or words are worth their weight in gold in helping to keep the eyes on the correct line. Very high tech indeed!

I have developed an equally low-tech Eccentric Fixation Test, which involves a test card clock with an H in the centre. The patient looks around the clock, calling the numbers out as they go. They decipher at which position on the clock, their gaze allows them to see the H most easily. I ask them to stick an acetate sheet with the clock on it, into the centre of their TV screen (using a smidgen of water). They then direct their gaze towards whichever number on the clock they could best see the H at, and, with training, the acetate sheet can be done away with.

For all our apps and technology, I maintain that it’s often the simple, low-tech techniques that can most easily make low vision more manageable.