Primary retinal telangiectasia

Primary or congenital retinal telangiectasia, more commonly called Coats’ disease or Coats’ syndrome, is a non-hereditary, developmental, retinal vascular disorder characterised by dilatation and exudation of the retinal vasculature, and an important cause of leucocoria in children.

Case report

A 13-year-old boy attended the emergency eye clinic with a one-day history of sudden onset loss of superior field of vision affecting his right eye. He had been trampolining the previous day.

There was no history of trauma, photopsia or floaters. He had no past ocular history and was in good general health. He was not premature and had achieved all developmental milestones.

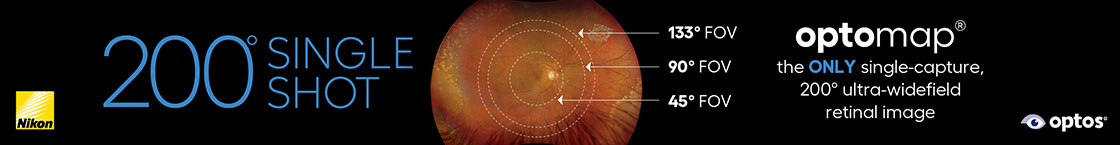

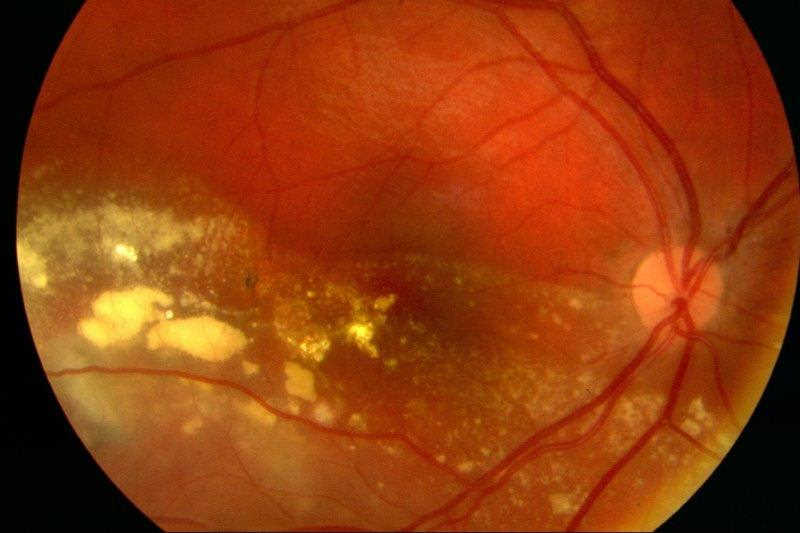

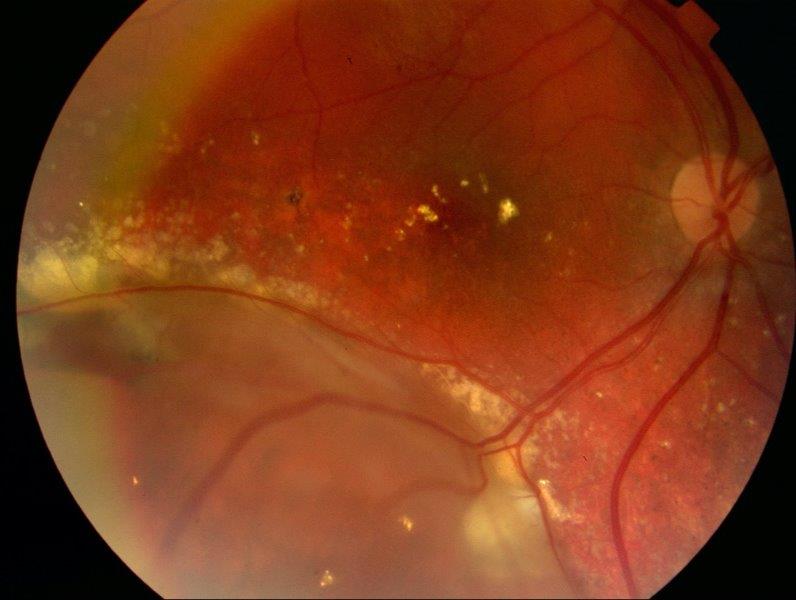

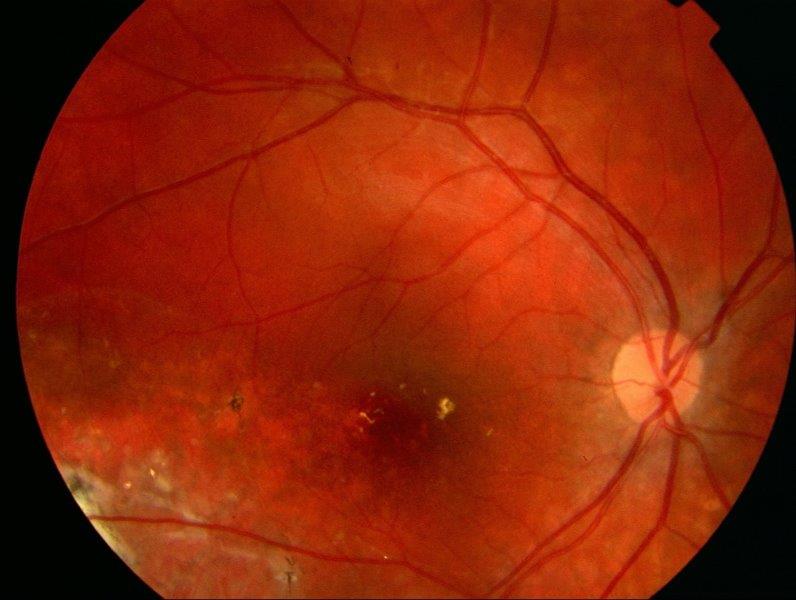

On examination, visual acuity was 6/24+1 right and 6/4 left. He had a relative afferent pupil defect in his right eye. He was orthotropic on cover testing. Anterior segment examination was normal. Dilated fundal examination of his right eye revealed marked intraretinal exudation with an inferior non-rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and multiple large telangiectatic vessels with light bulb-shaped aneurysms (Fig 1 and 2). The left retina was normal. Indirect indentation ophthalmoscopy of his right retina did not reveal any peripheral retinal tears. Ocular ultrasound revealed no posterior segment mass. A provisional diagnosis of Coats’ disease was made. Baseline bloods, including autoimmune and infective panels, were all normal. Both parents underwent fundal examination which was normal.

Fig 1. Exudative retinal detachment involving the macula

Fig 1. Exudative retinal detachment involving the macula

Fig 2. Classic light bulb-shaped telangiectasis

Fig 2. Classic light bulb-shaped telangiectasis

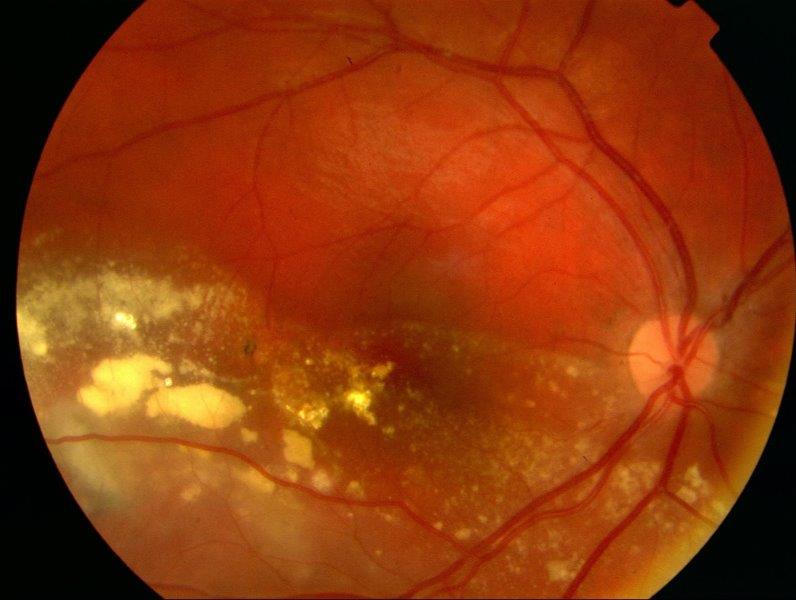

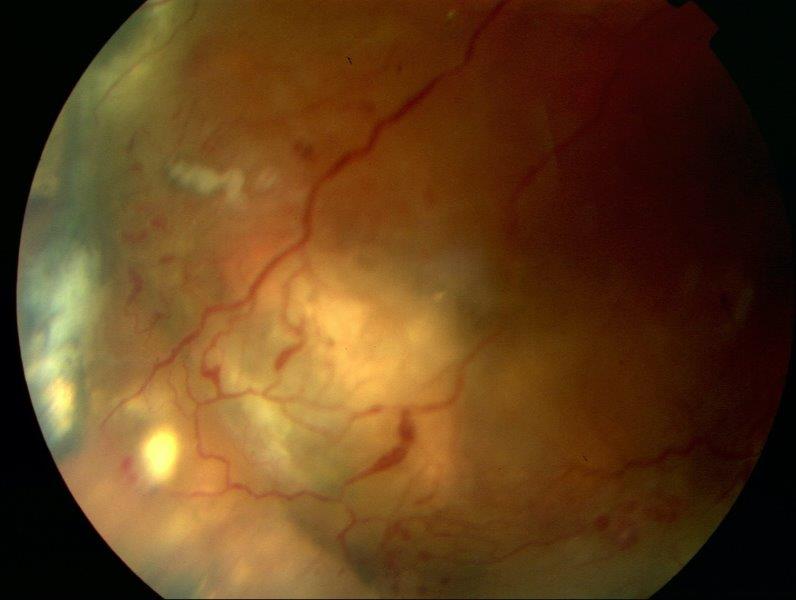

Considering the patient was very cooperative, Argon focal laser was carried out directly to the telangiectatic vessels in the right eye. The patient was seen two weeks later for further focal laser. A large degree of the exudate had resorbed with a reduction in the size of the detachment (Fig 3). Visual acuity had improved to 6/9-2. The patient had a further final episode of focal laser three weeks later. Visual acuity improved and has been maintained at 6/6 in this eye. Twelve months later the macula remains flat with peripheral subretinal fibrosis (Fig 4). There has been no reoccurrence of subretinal fluid or exudation.

Fig 3. Right eye two weeks after first episode of laser

Fig 3. Right eye two weeks after first episode of laser

Fig 4. Right eye 12 months post-treatment

Fig 4. Right eye 12 months post-treatment

History

In 1908, George Coats described “exudative retinitis,” which was best characterised as vascular abnormalities with massive subretinal exudation1. Today, congenital or primary telangiectasia goes by his name, Coats’ disease. It consists of dilated retinal capillaries, micro- and macroaneurysms, ischemia, nonperfusion and retinal vascular leakage. It typically presents unilaterally in males.

Four years later, Theodor Leber described “miliary aneurysms2,” which were quite similar clinically to the cases seen by Coats.

The term retinal telangiectasis was coined by the paediatric ophthalmologist Algernon Reese in 1956. He suggested that Coats’ disease and Lebers’ miliary aneurysms were one and the same, occurring either in child or adulthood3.

In 1968, Donald Gass described a new distinct entity which he called idiopathic juxtafoveolar retinal telangiectasis to differentiate it from Coats’ disease. This resulted in a detailed classification of all telangiectatic diseases in 19934.

By 2006, Lawrence Yannuzzi, using new imaging systems such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and high-speed stereo angiography, simplified telangiectasias classification into two distinct types: Type I, aneurysmal telangiectasia (Coats’ disease); and Type II, perifoveal telangiectasia5. Now when we refer to macula telangiectasia or MacTel, we are often talking about the common bilateral disease (Type II) that we see in middle-aged patients.

Aetiology

Coats’ disease is a non-hereditary ocular disease. The exact underlying mechanism remains unknown but a mutation of the norrin disease protein (NDP) gene has been proposed6, as this results in a deficiency of the protein norrin which regulates vascular development in the developing retina.

The pathophysiological processes of Coats’ disease include the breakdown of the blood-retina barrier at the level of the vascular endothelium, predominantly affecting the capillaries but often with focal arterial involvement. Subsequent leakage leads to aneurysm formation and vessel blockage with exudation of blood, lipid and fibrin into the intra and subretinal spaces7. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which plays an important role in the formation of normal retinal vessels and vascular permeability, is also elevated8.

The end result is exudative retinal detachment. Chronic detachment can involve the anterior segment secondarily and lead to neovascular glaucoma and blindness9.

Diagnosis

Coats’ disease (Type I, aneurysmal telangiectasia) encompasses a wide clinical spectrum. At one end of the spectrum are infants and children who can have massive exudative and heamorrhagic retinopathy with total retinal detachment. Typically, severe cases tend to present below the age of fifteen years. At the other end of the spectrum are middle-aged men who have retinal telangiectasia confined to a small area of the macula presenting with distorted vision.

Diagnosis should consider age, family history, laterality and presentation stage. Apart from clinical examination, fluorescein angiography, ultrasound, OCT and CT scanning are useful in confirming the diagnosis.

The differential diagnoses in a young child with retinal detachment causing leukocoria, include retinoblastoma, retinopathy of prematurity, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV), familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) and toxocariasis7,8,9.

In older patients with prominent exudates and telangiectasia, differentials include posterior uveitis, FEVR, vasoproliferative tumors and hamartomas, vein occlusions and retinal artery macroaneurysms.

Stages

Shields et al. proposed a staging system to describe the severity of Coats’ disease9 to help guide management and evaluate prognosis (Table 1).

|

Stage |

Clinical findings |

Vision <6/60 |

|

Stage 1 |

Retinal telangiectasias only |

Rare |

|

Stage 2a |

Telangiectasias and extrafoveal exudation |

50% |

|

Stage 2b |

Telangiectasias and foveal exudation |

50% |

|

Stage 3a |

Subtotal exudative retinal detachment |

75% |

|

Stage 3b |

Total exudative retinal detachment |

75% |

|

Stage 4 |

Total detachment with secondary glaucoma |

≈100% |

|

Stage 5 |

Advanced end-stage disease (pre-phthisis disease) |

≈100% |

Table 1. Staging of Coats’ disease

Management

Treatment is based on the severity of the disease. Mild cases can be observed, but if exudation, retinal or subretinal fluid is present, the mainstay of treatment is laser ablation or cryotherapy in areas of telangiectasia and nonperfusion8,9.

- Laser - Laser photocoagulation has historically been the most effective treatment. The goal of laser ablation in Coats’ disease is to obliterate abnormal vasculature and thus hyperpermeability of aneurysms9

- Cryotherapy - Cryotherapy is typically indicated if peripheral retinal telangiectasia with significant exudative retinal detachment impedes adequate laser photocoagulation8,9

- Surgery - If there is a total exudative retinal detachment, non-clearing vitreous haemorrhage and/or secondary complications, surgery may be needed for retinal reattachment or even enucleation8,9

- Adjuvant therapy - Anti-VEGF agents (such as Avastin) have been found to be effective in reducing subretinal fluid and exudation, but more studies are needed to further evaluate their efficacy in Coats’ disease10

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on disease severity at presentation. When mild, Coats’ disease typically progresses gradually and treatment can often lead to restoration of vision. Patients who present at a younger age (less than 5-years-old) have been reported to undergo a more rapid decline, while those older than 10 have a longer variable course11. Secondary complications include glaucoma, rubeosis iridis, phthisis bulbi, cataract and uveitis.

References

- Coats G. Forms of retinal disease with massive exudation. R Lond Ophthalmic Hosp Rep 1907-1908;17:440-525

- Leber T. Ueber Vorkommen durch eine Form von multipler Miliaraneurysmen charakterisierte Retinaldegeneration. F Arch Ophthalmol. 1912;81:1–14

- Reese AB. Telangiectasis of the retina and Coats’ disease. AM J Ophthalmol 1956;42:1-8

- Gass BDM, Blodi BA. Idiopathic juxtafoveolar retinal telangiectasis; update of classification and follow-up study. Ophthalmology 1993;100:1536-46

- Yannuzzi LA, et al. Idiopathic Macular Telangiectasia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:450-460

- Black GC et al. Coats' Disease of the Retina Caused by Somatic Mutation in the NDP Gene: A Role for Norrin in Retinal Angiogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(11):2031-2035

- Ghorbanian S et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Coats' Disease: A Review of the Literature. Ophthalmologica. 2012;227(4):175-182

- Sigler EJ et al. Current Management of Coats Disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59(1):30-46

- Shields JA et al. Classification and Management of Coats Disease: The 2000 Proctor Lecture Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131(5):572-583

- Villegas VM et al. Advanced Coats' Disease Treated With Intravitreal Bevacizumab Combined With Laser Vascular Ablation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:973-976

- Morris B et al. A Population-Based Study of Coats Disease in the United Kingdom I: Epidemiology and Clinical Features at Diagnosis. Eye. 2010;24(12):1797-1801

Dr Shanu Subbiah is consultant ophthalmologist at Eye Institute and Auckland District Health Board, specialising in cataract and refractive surgery, cornea, anterior segment and medical retina.