Regarding menopause and eye health

In recent years, a lot more has been written about how menopause’s hormonal changes can have certain physical and mental effects. But how much do we know about how those changes can affect eye health? And is what we know about menopause and menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) enough to substantiate changes to our clinical practice?

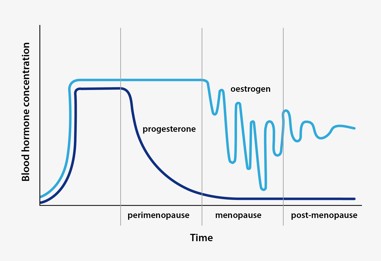

Menopause is the biological process ending monthly menstruation, resulting in the loss of ovarian follicular function and thus a woman’s ability to reproduce. It typically happens between the ages of 45 and 58, when the body’s production of oestrogen and progesterone decreases. Oestrogen doesn’t drop dramatically at first but tends to surge and drop more like a wave before resulting in a permanent reduction (Fig 1). It is this hormonal fluctuation (in the context of low progesterone) that causes menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, sleep and mood disturbances, weight gain and muscle and joint aches. It is also worth noting, however, that a relative increase in androgen levels can cause some women to experience additional symptoms associated with hyperandrogenemia, including facial hair growth and scalp hair loss.

Some women try to ameliorate the effects of these hormonal fluctuations with menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), previously known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT). MHTs differ in their levels of oestrogen, progesterone and sometimes even testosterone. There are also different modes of delivery, ranging from tablets to creams and intrauterine devices (IUDs). Use of MHT is complicated and its indication needs to be made on an individual basis. A meta-analysis conducted in 2019 found an association between some types of MHT, duration of MHT use and incidence of breast cancer¹. However, current international recommendations state MHT is safe and effective for most healthy females and the benefits outweigh the risks for those with significant menopausal symptoms.

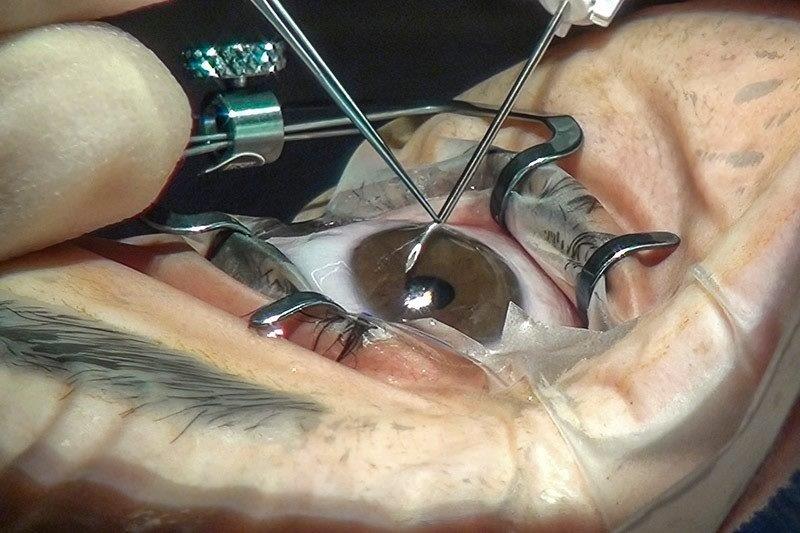

Glaucoma

There is an ongoing debate about whether menopause should be considered a sex-specific risk factor for glaucoma. One meta-analysis found an inverse linear relationship between age of onset of menopause and the risk of developing open angle glaucoma (OAG)2. This could indicate that early menopause (occurring in those aged <45, which can be due to chromosome issues, autoimmune conditions such as thyroid disease, epilepsy or individual genetics, or lifestyle factors such as history of smoking and low BMI) can be associated with an increased risk of developing OAG.

Preclinical rat studies found induction of ocular hypertension, larger vision loss (as measured by optomotor response) and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) loss (as measured by OCT) was associated with surgically induced menopause via ovariectomy3,4. One study also found oestrogen administration played a protective role in RGC layer integrity5; however, more studies are needed to confirm the relevance of oestrogen in glaucoma prevention.

Other animal studies investigated the effects of menopause on aqueous outflow and ocular compliance (related to the elastic properties of the sclera and cornea as well as blood circulation) to better understand whether these factors could play a role in the association between menopause and increased intraocular pressure (IOP). They found menopausal rats had a 34% decrease in aqueous outflow and 19% increase in ocular compliance when compared to controls6, which could result in some of the physiological factors associated with glaucoma. Overall, the literature seems to indicate that in animal studies, surgically induced menopause is related to increased IOP, increased aqueous outflow resistance and ocular biomechanics - factors we know can be associated with glaucoma. Thus, it could be possible that menopause sets the stage for glaucoma to develop5.

Human studies are limited. One found that in postmenopausal women there was an increase in IOP and biomechanics measures (resistivity index of vasculature, measures of retrobulbar blood flow), while MHT was associated with a decrease in IOP and resistivity index7. However, a far more recent meta-analysis and systematic review of randomised control trials (RCT) found that MHT did not result in a significant reduction in IOP⁸.

Studies have shown that early menopause doubles the risk of developing glaucoma, said Dr Noor Ali, a Canberra-based specialist in glaucoma, retinal disease and uveitis. “In age-matched female patients, those who have undergone menopause had average IOPs of 1.5-3.5mmHg greater than their premenopausal counterparts,” she said. “In addition, in vitro studies have suggested greater RGC loss after menopause5. While there are many confounding factors to be considered, as a practical note, postmenopausal women would benefit from a full assessment if there are any signs (of glaucoma) in screening.”

Ocular surface disease

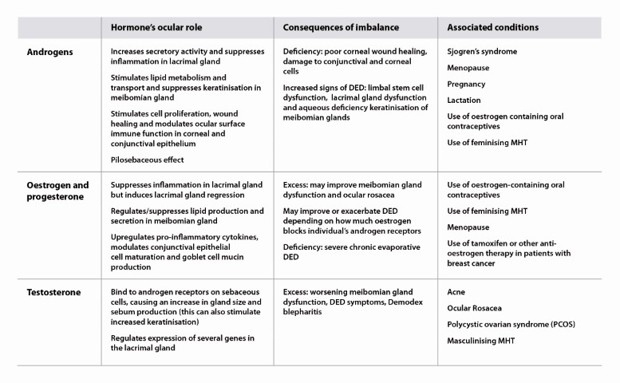

The TFOS DEWS II workshop report labels menopause status as an inconclusive non-modifiable risk factor for dry eye disease (DED)9. Understanding the role of androgens, oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone on the ocular surface can help us see why hormonal changes that mark menopause do not have a generalisable effect on DED (Table 1). Changing levels of different hormones will have different influences on factors contributing to the exacerbation or relief of DED. For example, decreased oestrogen levels may promote lipid production in the meibomian glands but suppress goblet cell mucin production. Thus, MHT can be both beneficial and harmful to DED patients.

Using basal and reflex Schirmer test and tear break up time (TBUT) results, one study found menopause increases the incidence of DED, but MHT can decrease its incidence7. Other studies found similar improvements associated with MHT in postmenopausal women when assessing DED symptoms12. It is important to note, however, that large-scale clinical trials in this area have not been performed.

Another paper suggested MHT could improve ocular surface function in postmenopausal women (especially in those whose menopause onset was before the age of 55). The systematic review and meta-analysis found that the improvement noted in oestrogen-only MHT was greater than that observed in MHT combining oestrogen and progesterone. Signs measured were TBUT, basal and reflex Schirmer test, plus corneal staining scores8. Interestingly, one study reported that greater doses of both oestrogen-only and oestrogen-plus-progesterone MHT resulted in worse DED symptoms in patients than in those who used lower doses of the same MHT therapies13. It was suggested the conflicting findings could be related to selection bias and patient subjectivity reporting/perception of symptoms.

Dr Stuti Misra, an optometrist-scientist and senior lecturer in the ophthalmology department at the University of Auckland who has researched this area, agreed study findings are contradictory when it comes to the benefits or drawbacks of MHT for patients with or without dry eye symptoms. For example, this can depend on the patient's age¹⁴, she said. “There is no one-size-fits-all with MHT. For example, both hyperandrogenemia and androgen deficiency can occur during menopause. Each condition requires different treatment options and, therefore, the effects of each treatment will differ significantly.”

The fluctuations in hormone levels during menopause also lead to varying levels of symptom relief or aggravation, said Dr Misra. “The timing of treatment is also crucial. Oestrogen can relieve symptoms early on, yet it can lead to adverse effects in later stages¹⁵. Interestingly, a large study of over 25,000 postmenopausal women using oestrogen-only MHT presented a greater risk of DED¹⁶.”

It’s difficult to comment on MHT and DED due to the lack of well-designed, methodologically robust longitudinal clinical trials, she added, suggesting that eyecare practitioners (ECPs) obtain a detailed history of DED symptoms during a patient’s regular menstrual cycle. “The exact history will create a database of patients' dry eye symptom history.”

Cataracts

There is some evidence suggesting an older age of onset for menopause is associated with decreased risk of cortical cataract, while postmenopausal oestrogen use is associated with a decreased risk of more severe nuclear sclerosis¹⁷. This could mean that oestrogen (endogenous/exogenous) could have a protective effect against cataract development. However, it’s important to note conflicting findings. For example, one study performed regression analysis to calculate the relative risks of various lifestyle factors (including the use of hormone therapy) in an individual developing a cataract that required surgery. MHT showed little if any association with reducing the risk of cataract development¹⁸.

“Menopause and cataracts, though seemingly unrelated, have intriguing links, primarily through hormonal changes and ageing processes,” said one Australasian cataract specialist who didn’t wish to be named. Intrigued, however, he decided to discuss the matter with ChatGPT and review the AI chatbot’s responses. These are the results:

- Ageing: both menopause and cataracts are associated with ageing. Thus, the timing of menopause coincides with the age range during which the risk for cataracts begins to rise

- Systemic health changes: menopause can also lead to systemic health changes, such as increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Both conditions are known risk factors for cataract development

- Hormonal changes and eye health: oestrogen is believed to have a protective effect on the lens of the eye where cataracts form. As oestrogen levels drop during menopause, this protective effect diminishes, potentially increasing the risk of cataract development

- Oxidative stress: menopause can lead to increased oxidative stress in the body, a significant factor in the development of cataracts as it can damage the proteins and fibres within the lens of the eye

- MHT: some studies suggest MHT might reduce the risk of cataracts, while others indicate a potential increase in risk. The relationship is complex and not fully understood

- Lifestyle factors: postmenopausal women might experience lifestyle changes which can indirectly affect eye health. For instance, changes in diet, physical activity and exposure to sunlight can all influence the health of the eye and the development of cataracts

- Genetic and environmental factors: genetic predisposition and environmental factors (such as UV exposure) play a role in both menopause and cataracts. Thus, these factors might intersect in ways that affect the risk and progression of cataracts in postmenopausal women

In conclusion, the surgeon surmised, the links are intertwined and thus confound our ability to truly, independently assess the role of menopause in cataract development and progression, as well as the effect of MHT on cataract progression.

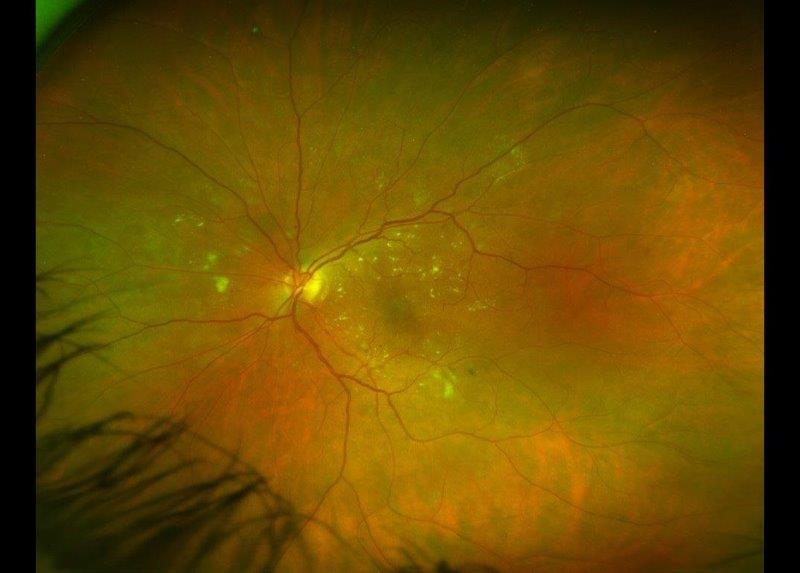

Macular degeneration

According to one study, an older age of menopause onset may be associated with geographic atrophy, while another found the risk of developing neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) was reduced by 70% in women using MHT and 40% in women who’d used MHT¹⁹. But these were isolated studies. Large, population-based studies have failed to consistently find the female gender as a risk factor for AMD when controlled for age, especially given women have a longer life expectancy, so we are clinically more likely to see more older women with AMD.

Dr Rachel Barnes, a specialist in retinal and inherited retinal disease, said she believes menopause is too complex and confounded by other factors to really incorporate clinically. “Although, of course, you should always take a full medication history when evaluating a new patient, which would include MHT.”

There appears to be a number of epidemiology studies in the literature, however, which demonstrate an association with MHT, the length of reproductive life or sex with the prevalence of various forms of AMD. But there is no consistency in the direction of the association, with some showing an apparently protective effect and others the opposite, said Dr Barnes. “I think at the end of the day, the strongest risk factor for AMD is age. Women tend to live longer and postmenopausal – ageing – women may be prescribed MHT, so often an apparent association disappears when you control for age. I think it is really important to investigate these potential links, but nothing I have read so far would make me change someone’s management with respect to MHT and AMD.”

The ECP’s role

Overall, it is difficult to separate the role of menopause and MHT in ocular pathology from confounding factors. For this reason, there is not enough justification to change our standardised guidelines when it comes to clinical workups for the ocular presentations discussed above. However, asking about a patient’s menopause status, age of menopause onset and use of MHT could be useful during history taking and help fill in the clinical picture. MHT also comes in different formulations and modes of delivery, so we should look up each particular MHT to help us understand the potential effects on the patient’s body and their eyes.

References

- Collaborative group on hormonal factors in breast cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet 2019; 394(10204):1159 – 1168.

- Kai J, Zhou M, Li D, Zhu K, Zhang X, Pan C. Reproductive factors and the risk of open angle glaucoma in women. J Glaucoma. 2023 Nov 1;32(11):954-961.

- Feola A, Fu J, Allen R, Yang V, Campbell I, Ottensmeyer A, Ethier C, Pardue M. Menopause exacerbates visual dysfunction in experimental glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2019 Sep;186:107706

- Fotesko K, Thomsen B, Kolko M, Vohra R. Girl power in glaucoma: the role of estrogen in primary open angle glaucoma. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2022 Jan;42(1):41-57.

- Douglass A, Dattilo M, Feola A. Evidence for Menopause as a Sex-Specific Risk Factor for Glaucoma. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2023 Jan;43(1):79-97.

- Feola A, Sherwood J, Pardue M, Overby D, Ethier C. Age and menopause effects on ocular compliance and aqueous outflow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020 May 11;61(5):16.

- Altintaş O, Caglar Y, Yüksel N, Demirci A, Karabaş L. The effects of menopause and hormone replacement therapy on quality and quantity of tear, intraocular pressure and ocular blood flow. Ophthalmologica. 2004 Mar-Apr;218(2):120-9.

- Hao Y, Xiaodan J, Jiarui Y, Xuemin L. The effect of hormone therapy on the ocular surface and intraocular pressure for postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2020 Aug;27(8):929-940.

- Craig J, Nichols K, Akpek E, Caffery B, Dua H, Joo C, Liu Z, Nelson J, Nichols J, Tsubota K, Stapleton F. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):276-283.

- Koetting C (2022). Do You know the ocular effects of HRT? Modern Optometry. Available at: https://modernod.com/articles/2022-nov-dec/do-you-know-the-ocular-effects-of-hrt

- Abelson M, Lines L. (2006). Hormones in dry-eye: a delicate balance. Review of Ophthalmology. Available at: www.reviewofophthalmology.com/article/hormones-in-dry-eye-a-delicate-balance

- Akramian J, Wedrich A, Nepp J, Sator M. Estrogen therapy in keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:1005-9.

- AlAwlaqi A, Hammadeh M. Examining the relationship between hormone therapy and dry-eye syndrome in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional comparison study. Menopause. 2016 May;23(5):550-5.

- Feng Y, Feng G, Peng S, Li H. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on dry eye syndromes evaluated by Schirmer test depend on patient age. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016 Apr;39(2):124-7.

- Sherwin B. Estrogen and cognitive aging in women. Neuroscience. 2006;138(3):1021-6.

- Schaumberg D, Buring J, Sullivan D, Dana M. Hormone replacement therapy and dry eye syndrome. JAMA. 2001 Nov 7;286(17):2114-9.

- Klein B, Klein R, Ritter L. Is there evidence of an estrogen effect on age-related lens opacities? The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Jan;112(1):85-91.

- Floud S, Kuper H, Reeves G, Beral V, Green J. Risk factors for cataracts treated surgically in postmenopausal women. Ophthalmology. 2016 Aug;123(8):1704-1710.

- Tomany S, Wang J, Van Leeuwen R, Klein R, Mitchell P, Vingerling J, Klein B, Smith W, De Jong P. Risk factors for incident age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology. 2004 Jul;111(7):1280-7.

Australia-based optometrist Layal Naji is a lecturer of optometry at the University of Canberra, a co-founder of the outreach optometry clinic at the Asylum Seekers Centre in Newtown, Sydney, and a regular contributor to NZ Optics.