Atopic dermatitis and retinal detachment

A 16-year-old Filipino male was referred to an ophthalmologist in British Columbia, Canada, with a gradual decline in vision in both eyes (right eye 6/48; left eye 6/21) with floaters. He was diagnosed with bilateral cataracts and listed for surgery to the right eye. His undilated retinal exam was reported as normal. Four months later, he was referred to the retinal service with complete loss of vision in his right eye. His past medical history was significant for severe atopic dermatitis for which he ‘d been prescribed tralokinumab (IL-13 inhibitor) and topical steroids. He admitted to eye rubbing and was using artificial tears intermittently.

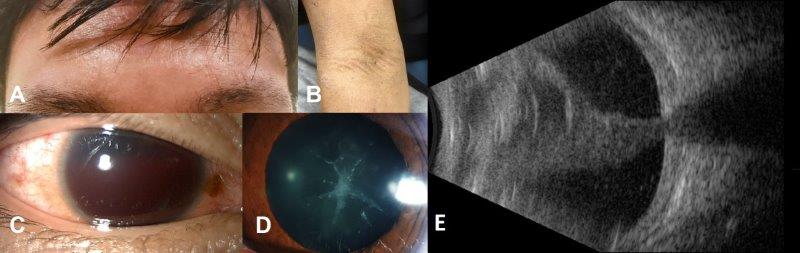

On examination, he had no light perception in the right eye and 6/21 in the left (corrected), with intraocular pressures of 5mmHg and 14mmHg, respectively. A hyphaema occupied over 70% of the anterior chamber of the right eye and obscured any view of the iris, lens and posterior segment structures (Fig 1). A central anterior capsular cataract was noted in the left eye, with areas of lattice degeneration in the peripheral retina. B-scan ultrasound of the right eye revealed a retinal detachment in a funnel-shaped configuration with vitreous haemorrhage.

Fig 1. Facial erythaema (A) and flexural skin thickening (B) from atopic dermatitis. Hyphaema, right eye (C); anterior subcapsular cataract, left (D). Axial B-scan (3 o’clock) of the right eye with funnel retinal detachment (E)

An anterior chamber washout of the right eye was performed, which revealed extensive neovascularisation of the iris and a white cataract. A total retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) and extensive cyclitic membranes were noted intraoperatively. A triple procedure, including cataract surgery, scleral buckling and vitrectomy was performed, but unfortunately the retina could not be reattached. The patient underwent cataract surgery and prophylactic retinal laser to the left eye several months later. At the most recent follow-up visit, his unaided vision was 20/20 in the left eye, with phthisis and no light perception in the right eye.

In summary, this is a case of a chronic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in the right eye with secondary iris neovascularisation and hyphaema, along with bilateral cataracts, in a patient with atopic dermatitis.

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as atopic eczema, is the most common inflammatory skin disease worldwide. It typically affects people with an ‘atopic tendency’ clustering with asthma, hay fever and food allergies. It manifests as generalised skin dryness, rash and itch and is characterised by remission and relapses with acute flares. The severity of AD is dependent on a complex interplay between environmental and genetic factors1. The prevalence is highest in infants (~20%) and often improves during school years with persistence into adolescence and young adulthood in 5-15%, and as high as 25% in Māori and Pacific peoples2. AD is associated with an increased prevalence of ocular comorbidities such as keratoconjunctivitis, keratoconus, glaucoma, cataract, lens subluxation and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD).

AD and rhegmatogenous retinal retachment

The first reported case of RRD associated with AD was reported in 1937 by Balyeat3. Since then there have been several observational studies and case reports published in the literature. A study of 8,992 patients with AD by Johns Hopkins University found a significantly increased risk of RRD in patients with AD (OR 3.22) compared to the general population4. Data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service database identified AD as an independent risk factor for the development of RRD, even after adjusting for other ocular comorbidities. They found that patients with severe AD had a higher risk of RRD (OR 2.88) compared to milder cases (OR 1.26)5.

Clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes

A study from Korea showed that patients with AD presented with RRD at a younger age compared to controls (23 vs 52 years), with bilateral involvement more common in the atopy group (21% vs 1%). They also experienced a higher rate of surgical failure due to PVR (45% vs 12%) and higher rates of re-operation (30% vs 10%). Despite comparable preoperative vision, patients with AD experienced worse visual outcomes than the control group (LogMAR 0.8 vs 0.3). The same authors also found that the risk of developing RRD within one year after cataract surgery was significantly higher in pseudophakic patients with AD (60% vs 26%)6.

Pathological mechanisms

Several theories have been put forward to explain this association, including the role of chronic intraocular inflammation with associated changes in the vitreous, leading to traction at the vitreous base. However, the most commonly accepted mechanism is mechanical trauma from excessive eye rubbing to relieve itching7. Several authors have reported signs of ocular trauma outside the retina in patients with AD, similar to those seen in eyes with traumatic RRD. Susuki et al identified breaks in the ciliary body and pars plana, in addition to those in the peripheral retina, at a similar frequency in patients with AD to those with ocular contusion from self-inflicted injury8.

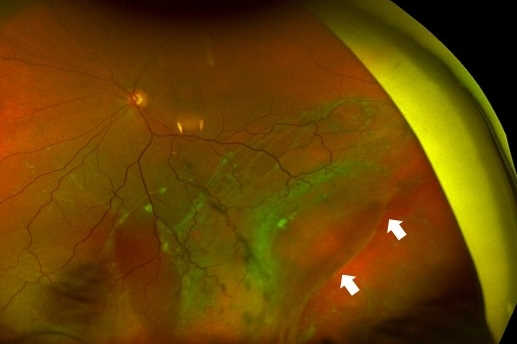

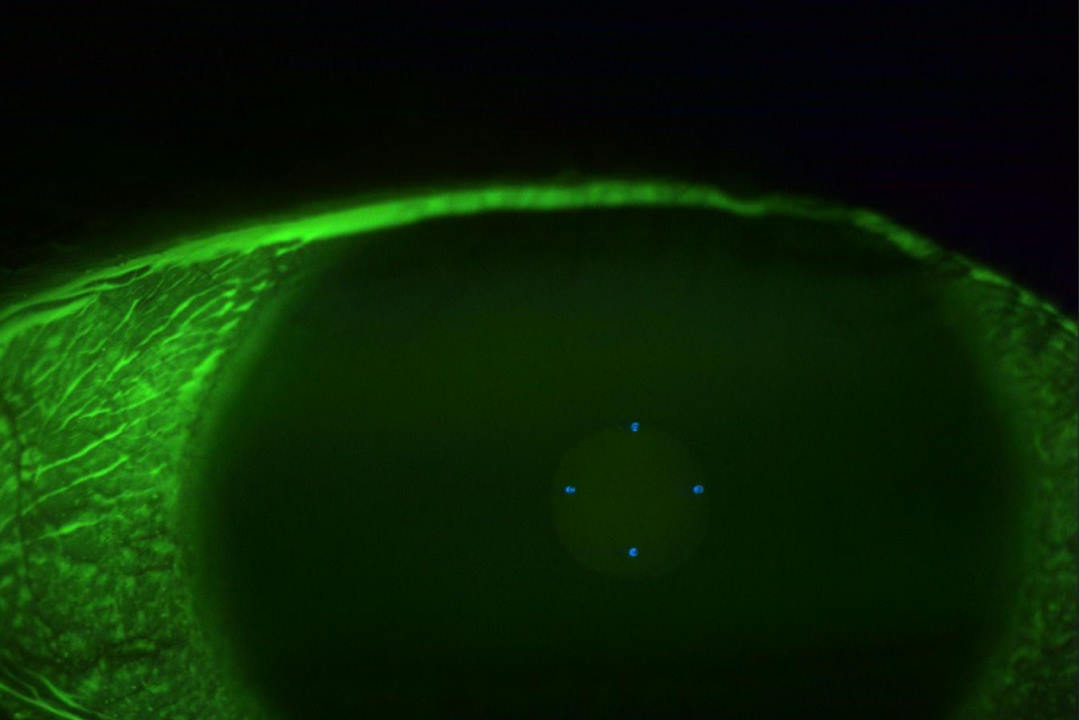

The retinal breaks seen in AD are also different. A retinal dialysis refers to a disinsertion of the retina from the vitreous base and is usually observed in eyes following trauma (Fig 2 above). Lee et al observed retinal dialysis in 16% of eyes with AD compared to 2% in the control group6 . Crescent-shaped retinal breaks, which differ from conventional horseshoe tears, are also frequently observed in eyes with AD9.

RRD in AD can also masquerade as acute panuveitis. Of the two cases that were published by Lim et al, the diagnosis of RRD was made after partial resolution of vitreous haze in one eye and on repeated B-scan ultrasound in the other10. Matuso et al analysed the aqueous humour of four patients with RRD and AD that had signs of moderate anterior uveitis. They found the contents consisted predominantly of photoreceptor outer segments indicative of RRD rather than intraocular inflammation11.

Retinal evaluation in AD patients

A dilated examination should be performed in all patients, given the high prevalence of associated ocular complications. The examination can be challenging because of oedema of the periocular tissues, photosensitivity and cataract. The anterior vitreous should be examined for pigmented cells. Topical and regional anaesthesia may be required to enable a detailed peripheral retinal examination looking for breaks at the vitreous base, which can be missed without scleral depression. B-scan ultrasonography should be performed when fundus evaluation is impeded by significant cataract. The detachments are usually very shallow initially because of the solid vitreous gel present in young patients with AD, thus repeat ultrasound exams may be required. Optical coherence tomography imaging is also influenced by cataract. However, a gross assessment of the macula status is usually still possible.

Treatment

The management of uncomplicated retinal breaks can be managed in a standard manner, with either retinal photocoagulation or cryotherapy. As this case demonstrates, the management of RRD in patients with AD can be challenging, with a strong propensity for PVR. The choice of surgical technique depends on the severity of the detachment and the surgeon’s preference. Scleral buckling surgery has traditionally been the preferred treatment option in younger patients where the hyaloid is firmly attached and can be combined with vitrectomy if severe PVR is present. Cataract surgery or lensectomy is required in more severe detachments to improve visualisation, allow for a more thorough vitrectomy and facilitate dissection and peeling of membranes.

Prevention

As this case highlights, early diagnosis and treatment is critical in preventing vision loss in patients with AD. This requires a multidisciplinary approach that should include the patient’s general practitioner, dermatologist and immunologist. A stepwise approach in the management of periocular dermatitis and keratoconjunctivitis is usually required to improve patient comfort and reduce the stimulus for eye rubbing, along with regular education on avoiding such behaviour. Finally, dilated eye examinations should be performed with careful attention to the vitreous base, with referral to a vitreoretinal surgeon if posterior segment involvement is suspected.

References

- Frazier W, Bhardwaj N. Atopic Dermatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2020,15;101(10):590-598

- Clayton T, Asher MI, Crane J, et al. Time trends, ethnicity and risk factors for eczema in New Zealand children: ISAAC Phase Three. Asia Pac Allergy. 2013;3(3):161-178

- Balyeat, R. Complete retinal detachment (both eyes): with special reference to allergy as a possible primary etiologic factor. Am J Ophthalmol. 1937;20(6):580–582

- Govind K, Whang K, Khanna R, Scott AW, Kwatra SG. Atopic dermatitis is associated with increased prevalence of multiple ocular comorbidities. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Jan;7(1):298-299

- Choi M, Byun SJ, Lee DH, Kim KH, Park KH, Park SJ. The Association with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and paediatric atopic dermatitis: a 12-year Nationwide Cohort Study. Eye. 2020;34(10):1909-1915

- Lee Y, Park WK, Kim RY, Kim M, Park YG, Park YH. Characteristics of retinal detachment associated with atopic dermatitis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021 Oct 11;21(1):359

- Oka, C, Ideta, H, Nagasaki, H, Watanabe, K, Shinagawa, K. Retinal detachment with atopic dermatitis similar to traumatic retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(6):1050–1054

- Suzuki J, Katsushima H, Maruyama I, Konari K, Sekine N, Nakagawa T. Comparison of retinal breaks between patients with atopic dermatitis and mentally retarded patients with self-inflicted ocular injury. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1997 May;101(5):446-9

- Kusaka S, Ohashi Y. Retinal detachments with crescent-shaped retinal breaks in patients with atopic dermatitis. Retina. 1996;16:312–316

- Lim WK, Chee SP. Retinal detachment in atopic dermatitis can masquerade as acute panuveitis with rapidly progressive cataract. Retina. 2004 Dec;24(6):953-6

- Matsuo N, Matsuo T, Shiraga F, Hosoda A, Kawanishi Y, Watanabe S, Ohtsuki H. Photoreceptor outer segments in the aqueous humor of patients with atopic dermatitis and retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993 Jan;115(1):21-5.

Dr Riyaz Bhikoo is an ophthalmologist with fellowship training in ocular oncology, medical and surgical retina. He is currently the William H. Ross retina fellow at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, and will return to New Zealand in 2022.