Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Herpes zoster (shingles) represents reactivation of latent herpes zoster virus in individuals with previous chickenpox infection. It occurs in one in three individuals over their lifetime, with significant sequelae, including recurrent episodes and post-herpetic neuralgia, which is pain that persists after the rash heals and is associated with depression. Herpes zoster also carries an increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction1.

In 10-20% of cases, herpes zoster affects the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve and is known as herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO)2. Of these patients, 50-70% will develop ocular complications such as corneal scar, loss of vision and, rarely, perforation of the eye2,3. The most serious complications are evident when the nasociliary nerve of the ophthalmic division is involved, as this often signifies intra-ocular involvement2.

Herpes zoster is most common in the elderly, patients who are immunosuppressed and those with HIV. This vulnerable group is more likely to have chronic disease with greater complications and a poorer visual prognosis. The higher risk of infection associated with HIV requires consideration of HIV testing in patients presenting with herpes zoster under the age of 45 years2.

HZO disease

During the acute eruptive phase of herpes zoster, HZO can present as a periocular rash with eyelid erythema and vesicles, which can also develop into periorbital oedema and ptosis (Fig 1). Commonly, a conjunctivitis also develops with hyperaemia, haemorrhages, chemosis and a papillary reaction. As the inflammation resolves and the vesicles crust, there may be residual ptosis, lid scarring, entropion, ectropion and even lid necrosis2.

Fig 1. A female with a periocular vesicular rash in the distribution of the left ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, causing periorbital swelling and associated ptosis

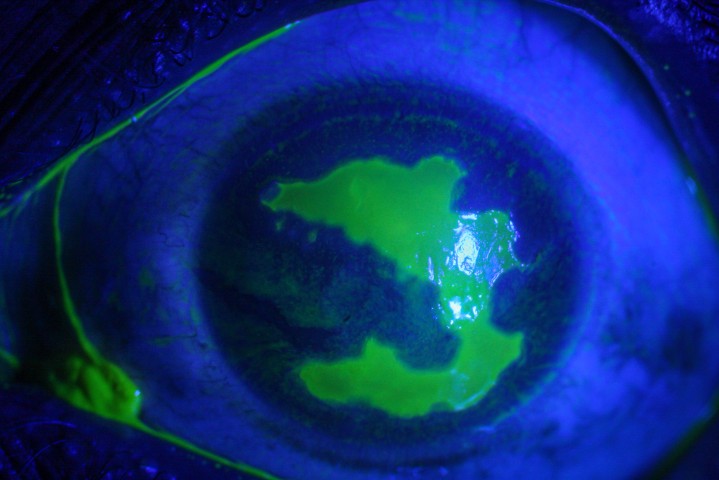

Corneal disease is the most common intraocular complication, usually manifesting as punctate epithelial keratitis with pseudodendrites (Fig 2). Corneal pathology can also present as anterior stromal keratitis or disciform keratitis; long-term inflammation may progress to extensive corneal neovascularisation then subsequent lipid deposition, scarring and possible perforation. Furthermore, chronic epitheliopathy and the nerve damage inherent to HZO may result in neurotrophic keratitis with reduced corneal sensation and loss of corneal epithelial integrity, even months after initial presentation (Fig 3)2,4.

Fig 3. A patient with corneal melt; a late complication of chronic corneal inflammation and loss of corneal epithelial integrity

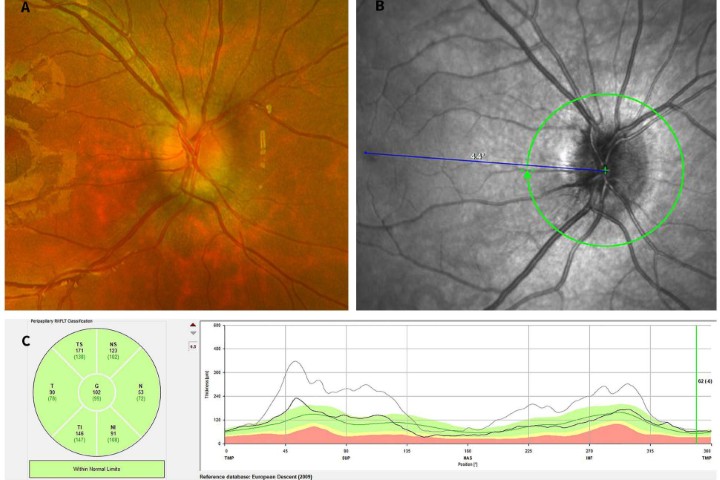

Uveitis, in the form of anterior chamber cellular reaction, occurs in approximately 32% to 46% of HZO cases and is usually prolonged for months. It has been identified as a risk factor for both recurrent and chronic disease, so it is important to taper topical steroids much more slowly than a typical anterior uveitis, ideally over at least three months2,4,5. With chronicity of uveitis, sectoral iris atrophy can develop and cause ill-defined iris margins and transillumination defects. Secondary glaucoma may occur due to inflammation of the trabecular meshwork and accumulation of inflammatory debris from associated uveitis, resulting in a rise in intraocular pressure. Early initiation of topical steroids is usually adequate therapy, however, it is important to monitor intraocular pressure at every examination of these patients to minimise glaucomatous damage2,4.

Rarer presentations of HZO include scleritis, which can occur acutely two to three months after the disease (Fig 4). In some cases, it can extend to the cornea and cause vascularisation and lipid deposition. Also uncommon, but severely vision-threatening, are the posterior segment complications of acute retinal necrosis and acute optic neuritis. The devastating morbidity that could result from these complications warrants thorough dilated examination and adequate antiviral treatment, particularly in the elderly and immunosuppressed patients2,4,5.

Fig 4. Scleritis with inflamed vessels extending towards the cornea

In addition to the risks of disease sequelae discussed above, HZO patients have a predilection to the development of cataract due to therapy with an extended course of topical steroids, usually in the context of chronic uveitis4. They are also at risk of diplopia due to external ocular motor palsies developing during the disease, but this usually resolves with time2,5. As these conditions cause transient alterations in vision, they affect quality of life and the patients’ ability to continue with work and independence, so recognising the clinical signs of disease and early referral to an ophthalmologist is essential.

Cataract surgery in HZO

Cataract surgery in patients with previous HZO uveitis or keratitis is often complicated by corneal scar and difficult iris and pupil management. Whilst these patients do have a slightly higher rate of intra-operative complications, post-operatively only 3.5% develop corneal oedema and 14% have persistent post-operative inflammation at one-month follow-up. A very high rate of recurrence of zoster eye disease is observed following surgery. Recurrence occurs in 40.4% of patients and is more common in subjects with a shorter time of quiescence prior to surgery and subjects with more recurrences. At 12 months, 12.3% of subjects have poorer vision than pre-operatively due to complications of zoster recurrence6.

To reduce the rate of recurrence following surgery, it’s ideal to prolong the period of disease quiescence to one year where possible. The role of antivirals in zoster is still unclear and prophylaxis regimens are surgeon specific. An example of such a regimen, if a patient is not already on antiviral therapy, is to start antivirals on the day of cataract surgery and continue for three months in those with simple HZO disease, and for one year in those with previous recurrences or less than one year of quiescence.

HZO and cardiovascular disease

Patients with HZO are more likely to have pre-existing cardiovascular comorbidities of hypertension, diabetes and coronary heart disease. Studies have demonstrated that HZO patients had a significantly higher risk (4.5-fold) of developing a stroke in the year following diagnosis compared with non-HZO patients. The risk is highest one to two months following HZO and may arise from cerebral vasculitis1. Therefore, it is essential to optimise these patients’ cardiovascular risk factors and ensure they are aware of the signs, so they can seek urgent medical care.

The shingles vaccine

Shingles vaccination with Zostavax has been demonstrated to decrease subsequent herpes zoster episodes by 51% and post-herpetic neuralgia by 67%7, while recent evidence also points to a possible reduction in risk of stroke in vaccinated populations8. Although the rate of herpes zoster increases sharply with age, over 50% of episodes still occur in those aged under 65 years3,9.

In New Zealand, Zostavax has been fully subsidised for people aged 65 years since April 2018. There is currently a two-year catch-up period for people aged 66 to 80 years, so from now until 31 December 2020, people aged over 65 years can also receive a subsidised vaccine before they turn 8110.

It is significant that recent trends have demonstrated an increasing burden of HZO in middle-aged individuals, ranging from 31 to 60 years9. Although not subsidised, the vaccine is available for purchase to those aged 50-64 years and, given the morbidity associated with HZO, vaccination is strongly recommended for this age group. However, it is contraindicated in people taking immunosuppressive treatment, with some exceptions for those on mild immunosuppression, eg. low dose prednisone.

Recurrence of inflammation in HZO is thought to be due to cell-mediated immunity to the virus present within ocular structures2. The Zostavax vaccine increases cell-mediated immunity against herpes zoster virus and, within the eye, may result in a flare of ocular inflammation. The original large study of safety and efficacy of Zostavax (n=38,546) excluded individuals with previous herpes zoster7. There are some reports of complications following vaccination in individuals with previous HZO, including flare of uveitis, keratitis and, rarely, perforation requiring corneal transplantation or enucleation11,12,13. Despite some concerns regarding vaccination safety in individuals with HZO, and the paucity of data surrounding this, Zostavax is currently given to individuals with a previous history of herpes zoster without further monitoring. In practise, vaccination is probably safe after one year of disease quiescence but, ultimately, the vaccine should be given with caution and upon discussion with the patient’s ophthalmologist.

References

- Lin HC, Chien CW, Ho JD. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus and the risk of stroke. Neurology 2010;74:792-797

- Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus: natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology 2008;115:S3-S12

- Niederer RL. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus – clinical presentation, vaccines and what’s new in 2019. NZ Branch RANZCO Annual Scientific Meeting. Auckland May 2019

- Womack LW, Liesegang TJ. Complications of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. JAMA Ophthalmology 1983;101:42-45

- Yawn BP, Wollan PM, St Stauver JL, et al. Herpes Zoster – Eye Complications: Rates and Trends. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2013;88(6):562-570

- Lu L, Sims J, McGhee CNJ, Niederer RL. High rate of recurrence of herpes zoster related ocular disease following phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery 2019;45(6):810-815

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnston GR et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. New England Journal of Medicine 2005;352(22):2271-2284

- Klaric JS, Beltran TA, McClenathan BM. An association between herpes zoster vaccination and stroke reduction among elderly individuals. Military Medicine 2019;184(Suppl 1):126-132.

- Kong CL, Thompson RR, Porco TC, et al. Incidence Rate of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus: A retrospective cohort study from 1994 through 2018. Ophthalmology 2020;127:324-330

- The Immunisation Advisory Centre. https://www.immune.org.nz/vaccines/available-vaccines/zostavax. Accessed online 22 March 2020

- Hwang CW, Steigleman WA, Saucedo-Sanchez E, Tuli SS. Reactivation of herpes zoster keratitis in an adult after varicella zoster vaccination. Cornea 2013;32(4):508-9.

- Jastrzebski A, Brownstein S, Ziai S, Saleh S, Lam K, Jackson B. Reactivation of herpes zoster keratitis with corneal perforation after zoster vaccination. Cornea 2017;36:740-742

- Trollip JC, Sims JL, Niederer RL. Band keratopathy in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. NZ Branch RANZCO Annual Scientific Meeting. Auckland May 2019

Dr Rachael Niederer completed her fellowship training in uveitis and medical retina at Moorfields Eye Hospital. The recipient of several awards and an experienced author and presenter, she now works at Greenlane Clinical Centre and Auckland Eye as a uveitis and medical retina specialist and is a senior lecturer with the Department of Ophthalmology at Auckland University.

Dr Haya Al-Ani completed her undergraduate medical training at the University of Auckland, including an elective placement in ophthalmology at St Thomas’ Hospital, London. She has a particular interest in population health as well as ophthalmology and has authored original research in both areas. She is currently a junior clinical research fellow at the Department of Ophthalmology, Auckland University, and works at Greenlane Clinical Centre.