Adopting a different world of eyecare – Mercy Ships sail again!

There are many things I’ve learnt during my time volunteering on board Mercy Ships’ Global Mercy, the largest purpose-built civilian hospital ship in the world. Before I joined Mercy Ships, I’d expected I would learn about running a hospital on a ship, maritime rules and regulations, healthcare systems in developing countries and more about living in a multi-cultural, close-knit community. What I didn’t expect was to encounter an ophthalmic surgical technique I’d never heard of and moral and ethical challenges I’d previously considered unquestionable.

Phacoemulsification is the mainstay of cataract surgery in the developed world. Surgeons worldwide have fine-tuned this technique to provide excellent outcomes for millions of patients, including in New Zealand. Unfortunately, phacoemulsification isn’t accessible for everyone, with most developing countries facing huge access barriers for surgeons and patients. A lack of training, machinery and technology and biomedical technicians, plus unreliable supply chains for consumables, as well as cost, all hinder phacoemulsification becoming the standard of care.

Even if a surgeon can afford a phacoemulsification machine, that cost is sometimes passed on to the patient, exacerbating the existing financial barrier. If a surgeon is fortunate enough to have a machine donated, there is no guarantee the machine will be maintained, since biomedical technicians are a rare and precious resource. The ongoing cost of consumables, especially foldable IOLs, is yet another barrier. Even assuming the equipment and biomedical support is available and supply chains are stable, being able to access training in this specialised surgical technique is another critical consideration. Trainees face time away from their clinic, a lack of access to teaching and the cost of such courses, which are often high hurdles for local surgeons who would like to keep up with their international colleagues if only they could.

Alternative routes

Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) is an excellent alternative for ophthalmic surgeons in developing nations. This is the primary surgical technique used and taught as part of the Mercy Ships ophthalmic programme. There are many reasons for this. Firstly, its predecessor, extracapsular extraction (ECE), uses a much larger incision of 10-12mm, which requires stitches. Generally, this procedure causes a high amount of induced corneal astigmatism and recovery takes longer. MSICS uses a 6-8mm scleral tunnel which is self-sealing, with the lens removed whole through the incision. The combination of the smaller incision and lack of stiches causes less post-operative-induced astigmatism than ECE. The stitch-free procedure also simplifies the post-operative follow-up care, especially for patients who struggle to access ophthalmic care. Recent innovative studies have shown MSICS, with the combination of phacofracture and a 2mm incision, to have even less induced astigmatism1.

A fast surgical technique, MSICS is also approximately a quarter of the cost of phacoemulsification and far less dependent on more advanced technology. Many studies have compared the two techniques and found no difference in post-operative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), although uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was better following phacoemulsification. Patients in developing countries often present later with ocular conditions, resulting in a higher rate of very dense cataracts, which can be more difficult to operate on with phacoemulsification and easier to extract with MSICS.

MSICS has revolutionised cataract surgery across the developing world and I am amazed it is not something we are more aware of, given its prevalence and positive impact worldwide.

Adama’s story

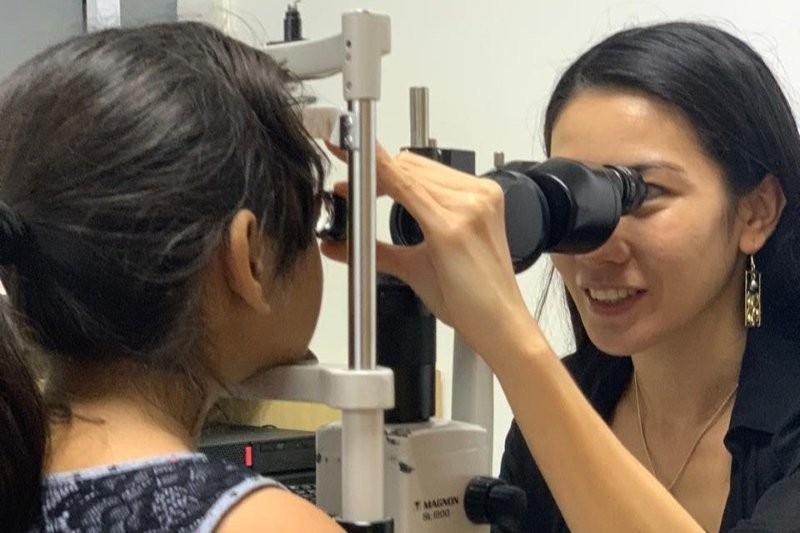

Ella Hawthorne examines Adama aboard Global Mercy

On this trip, I was confronted by moral and ethical issues that I have never had to consider before. To fully explain these, I have to tell you Adama’s story.

I met Adama when he was seven years old, during our days of patient selection in Dakar, Senegal. He was a quiet but very attentive boy. During his eye assessment he followed every instruction we gave him and was incredibly well behaved – a perfect patient! Unfortunately, he had a dense cataract in one eye. As we spoke more with his mother, Fatou, over the coming months, we learned more about him.

As a small child, Adama was adventurous and loved to explore, but he would frequently injure himself, causing his parents constant worry. After his many tumbles, they took him to a doctor, who diagnosed him with bilateral congenital cataracts. We are so lucky in New Zealand to have robust paediatric screening and referral pathways in place for paediatric cataracts, including midwives, GPs and Whānau Āwhina Plunket, leading to early diagnosis and surgery. Our public health system works very well, so much so that Adama was one of the first children I’d ever seen with a cataract.

Fatou was told by the surgeon that at four years old Adama was too young to have surgery on both eyes. Based on that advice, the family found enough money to pay for surgery for his left eye only. There may have been other contributing factors, but to my mind, and to the surgeons who saw him on board Global Mercy, removing the cataract in only one eye was completely unethical. Even though his monocular vision had improved, his depth perception was non-existent. He struggled playing sports or riding a bike and often missed out when his friends were playing. I had never been forced to consider the ethics of only operating on one eye for children with congenital cataracts. In New Zealand we have the unconscious privilege of knowing that children in Adama’s situation automatically receive surgical care for both eyes.

Ella holds Adama as Dr Paulius Rudalevičius checks his eyes post surgery

Fortunately, we were able to operate on his right eye during our time in Senegal earlier this year. At his six-week follow up, while his vision was slightly reduced – which was to be expected after three years of sensory deprivation – he had binocular vision for the first time in years. He has been referred back to local healthcare providers for ongoing ophthalmic care and visual rehabilitation. Fatou celebrated with us and said Adama had been able to join in with his friends, doing all the things he couldn’t before! It was a joy to be able to share her excitement and happiness for her son and his future.

A team to be proud of

When I came aboard Global Mercy in January, I was only meant to stay for six months. I quickly realised, however, that there was something special about working on this ship. We are privileged to meet kind and grateful patients who are changed inside and out from the care and free surgery they receive. It is an honour to serve them alongside the incredible healthcare heroes running this floating miracle of a hospital and the many others who literally keep the ship afloat! I’ve extended my commitment to Mercy Ships to 2025 and I am thrilled to continue to be a part of this life-changing work. If you are at all interested in coming aboard to serve, I would be happy to answer any questions. I can promise you this: your life will be forever changed from working here!

- www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK582123/

To learn more about volunteering with Mercy Ships visit www.mercyships.org.nz.

Ella Hawthorne has taken leave from her job as an optometrist at Judd Opticians in New Plymouth while she continues to be the latest ophthalmic team manager with Mercy Ships. This is her second article from Global Mercy for NZ Optics.