Can shades reduce AMD risk?

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive blinding disease affecting the central retina and is a leading cause of vision loss globally. It is estimated to affect close to 9% of the worldwide population, which is expected to total 288 million patients by 20401. Unsurprisingly, numerous epidemiological studies have explored the underlying causes and associations with AMD onset and disease progression.

At the centre of much of the debate, stemming from varied and inconsistent evidence, is AMD’s association with sunlight exposure. While the link is complex and multifactorial, several studies suggest long-term exposure to UV and blue light without eye protection may contribute to AMD onset and development. The controversy surrounding this association may stem from the methods used to measure lifetime sunlight exposure. The most notable studies rely on extensive questionnaires or interviews to quantify exposure, which introduces potential inaccuracies due to question quality, participants' long-term memory and subjective biases.

The intensity of UV radiation in New Zealand is well documented and quantified by the UV Index (UVI), with peak levels occurring from October to March2. These high levels are influenced by our proximity to the sun during December and January, minimal air pollution and the depletion of the ozone layer above the islands2. While these conditions create ideal settings for days at the beach and engaging in quintessential Kiwi activities with family and friends, they also have potential impacts on ocular health, including an increased risk of AMD development and progression.

As New Zealand health professionals, we are particularly concerned about the impact of high UV levels on ocular health and many optometrists advocate protective measures such as wearing hats and sunglasses. Yet the extent of their impact on AMD remains uncertain.

The evidence

Several prominent studies, including two in the US conducted in the early 1990s and 2000s, shed light on the association between sunlight exposure and AMD. The Beaver Dam Eye Study, involving over 5,000 participants, showed individuals exposed to more than five hours of summer sun during their teens and 30s were more likely to develop late AMD during a 10-year follow-up, compared to control groups3. The study also identified a protective effect of wearing hats and sunglasses on AMD onset. Notably, no correlation was found between AMD and UVB exposure, winter-sunlight exposure, or an individual's skin sun sensitivity3.

In Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, researchers interviewed 838 watermen who work outdoors to collect detailed histories of ocular sun exposure. Their findings suggested high levels of exposure to blue and visible light over the previous two decades were associated with an increased prevalence of late AMD4. Among those with late AMD, the average sunlight exposure was 48% higher than that of age-matched controls4.

Additionally, researchers from Japan’s Kagoshima University employed image analysis of the upper cheek area to objectively quantify skin features such as wrinkling and hyperpigmentation, which serve as quantitative biomarkers of lifetime sun exposure5. Their results indicated a positive relationship between facial wrinkle length and late AMD prevalence. Interestingly, individuals with late AMD tended to have fewer hyperpigmented spots, a phenomenon possibly related to unique skin characteristics such as resistance to tanning5.

Finally, a comprehensive meta-analysis conducted by Chinese researchers yielded intriguing results. Encompassing 14 studies and nearly 44,000 participants, the analysis assessed time spent outdoors, occupational exposure, calculated sunlight exposure and sun-avoidance behaviours such as wearing sunglasses or hats. Contrary to expectations, the meta-analysis did not find a significant association between sunlight exposure and an increased risk of AMD6. Furthermore, individuals who regularly practised sun-avoidance behaviours showed no decrease in the risk of developing AMD6.

Conclusion

Overall, the relationship between sunlight exposure, wearing sunglasses and AMD risk is complex. Further studies using more objective measures of sunlight exposure are needed to obtain accurate and reliable results to guide clinical decision making.

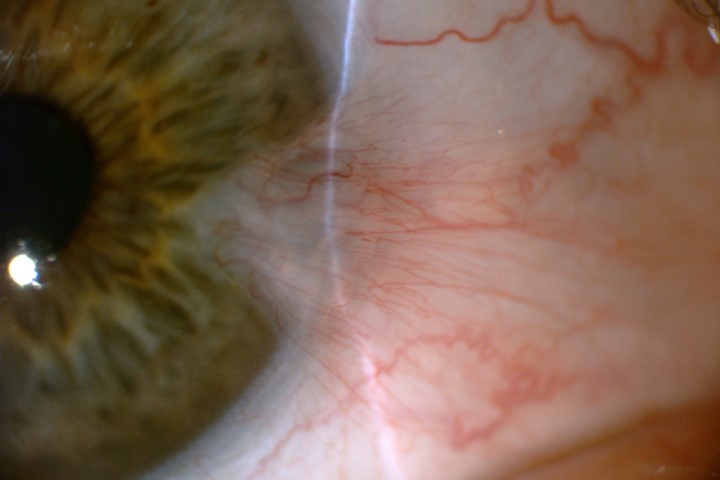

Regardless of the specific link between sunlight exposure and AMD, the known associations with other UV-related conditions, such as cataracts, ocular cancer and pinguecula/pterygium (see previous story) underscore the importance of UV protection7. In light of this, encouraging patients of all ages to wear UV-filtering sunglasses, wide-brimmed hats and avoid direct sun exposure during peak sunlight hours (typically between 10am and 4pm) should be a routine part of clinical discussions.

References

- Wong W, Su X, Li X, Cheung C, Klein R, Cheng C, Wong T. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014 Feb;2(2):e106-16

- McKenzie R. (2017). UV radiation in the melanoma capital of the world: What makes New Zealand so different? AIP Conf Proc.

- Tomany S. (2004). Sunlight and the 10-year incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. AMA Arch Ophthalmol, 122(5), 750.

- Bressler N. (1989). The grading and prevalence of macular degeneration in Chesapeake Bay Watermen. AMA Arch Ophthalmol, 107(6), 847.

- Hirakawa M, Tanaka M, Tanaka Y, Okubo A, Koriyama C, Tsuji M, Sakamoto T. (2008). Age-related maculopathy and sunlight exposure evaluated by objective measurement. BJO, 92(5), 630–634.

- Zhou H, Zhang H, Yu A, Xie J. (2018). Association between sunlight exposure and risk of age-related macular degeneration: A meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol 18 (1).

- Walsh K. (2009). UV radiation and the eye. Optician, 237(6204), 26-33.

Aidan Quinlan is a therapeutic optometrist at Bay Eye Care in Tauranga. He has a particular passion for specialty contact lenses, orthokeratology and dry eye and ocular disease management.