Case study: does myopia stop for red lights?

Myopia management has fascinated me since my university days. So, after I graduated, I set up New Zealand’s first myopia management clinic in Hamilton’s Rose Optometry. Back in 2009 that was considered pretty unusual, as myopia management was not as widely understood in the profession and people had not realised we were facing a global explosion of myopia.

While our myopia clinic treats many conditions in children and adults, we have a particular focus on myopia and I remain a strong advocate of early and proactive intervention to slow or halt its progression in young children. In fact, we have a policy of not prescribing simple corrective lenses to myopic children except as an adjunct to a management therapy such as orthokeratology (ortho-k) or low-dose atropine drops.

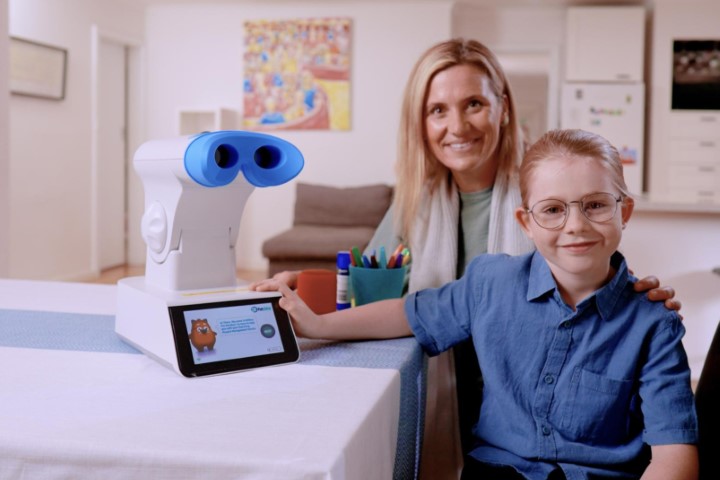

Our clinic carries all the available brands of spectacle lenses, ortho-k lenses, low-dose atropine, plus soft myopia-control contact lenses. In 2023, we were an early adopter of the repeated low-level red-light (RLRL) Eyerising Myopia Management Device, which we added to our treatment options as an adjunct therapy, mostly with ortho-k. We currently have more than 50 patients using RLRL and I have seen very good results with no side effects.

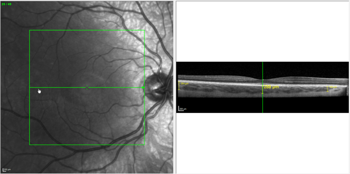

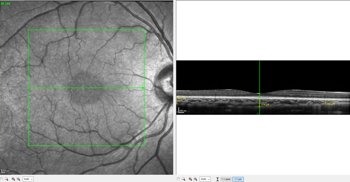

In a significant subset of patients, I have recorded an unusual response. On average we are seeing a reduction of 0.1mm to 0.15mm in axial length, which so far appears to be sustained. We regularly review the choroid and a range of other ocular measurements with the Heidelberg Spectralis OCT. This is about to be upgraded with the FLIO module and choroidal thickness difference maps, which will allow us to view the macular and accurately measure the choroid’s thickness repeatably, as opposed to the variations inherent in manual measurement. We do this before treatment, then at one, three and six months then every six to 12 months, depending on the patient. We have not seen any loss of vision or damage to the retina.

Case one: ortho-k and RLRL

Patient one first presented in January 2017, a couple of months before his ninth birthday. He had refraction of:

- OD: -4.25/-0.75 x 15

- OS: -5.00/-1.25 x 175

- Axial length: R 25.53mm, L 25.74mm

- Choroidal thickness: 276μm

- Visual acuity: 6/6

After an initial examination and assessment in consultation with his parents, we initiated ortho-k. The patient responded reasonably well in the first two and half years, recording an axial length of R 25.79mm, L 25.91mm.

By September 2021, when the patient was about 12.5 years old, there had been an increase in the rate of axial lengthening to R 25.98mm, L 26.09mm, at which point we started the patient on 0.01% atropine. This stabilised the situation and we recorded no growth for a little more than a year.

By October of 2022, axial lengthening was measured at R 26.06mm, L 26.17mm and we increased the atropine to 0.02%. We continued to see axial lengthening over the next year, despite gradually increasing the strength of the atropine solution to 0.1%.

By November 2023 axial length was R 26.16mm, L 26.26mm. At this point we suggested to the patient and his parents that we stop atropine and add RLRL therapy to his treatment regimen. They agreed and in December 2023, the patient returned to collect the Eyerising device. He was briefed on its use and his axial length was recorded as R 26.15mm, L 26.27mm, which became the baseline to assess the treatment’s effectiveness.

Being almost 16 years old, he had no problem using the device, which is designed to be simple enough for children of seven or younger to use. The patient responded well to the treatment, with his axial length recorded as R 26.13mm, L 26.24mm at one-month follow-up. He reported no side effects.

Fig 1. Patient one’s axial length graph

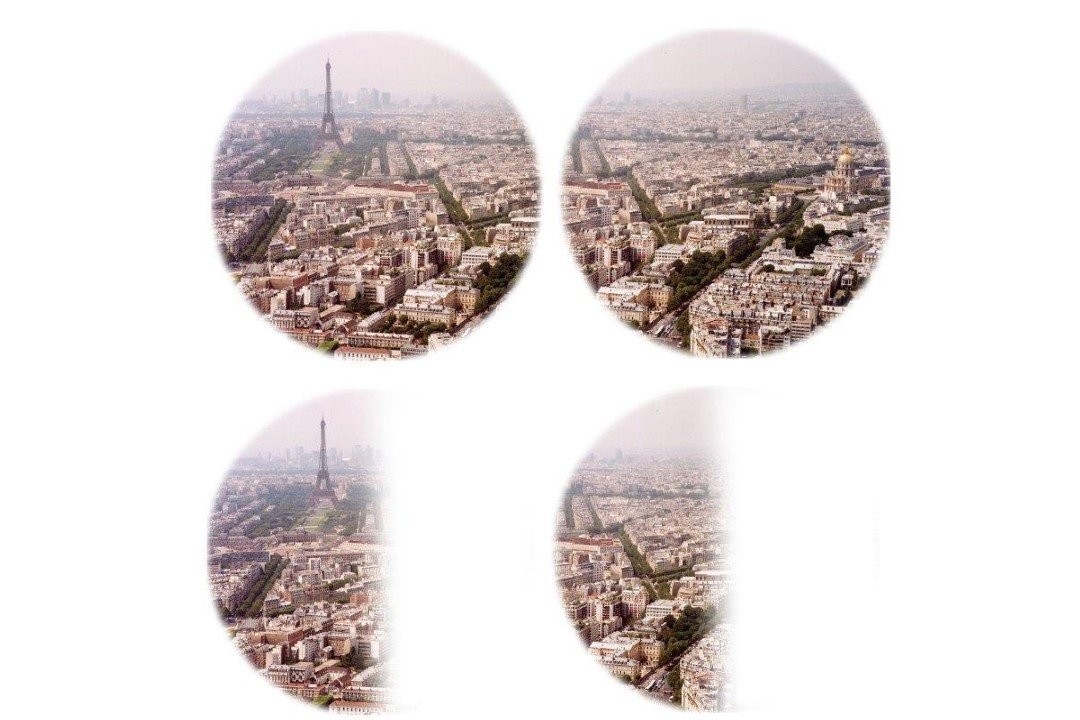

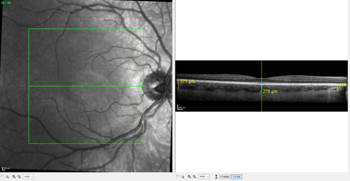

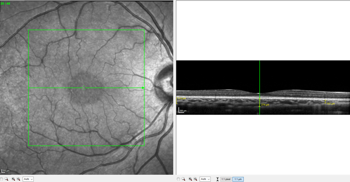

Figs 2 and 3. Patient one’s choroidal thickness pre-treatment (top) and at one-month follow-up

When he returned in February 2024 for his second follow-up, the axial length in both eyes had decreased significantly to R 26.00mm, L 26.05mm (Fig 1). There was also an increase in choroidal thickness from 276μm to 288μm (Figs 2 and 3). The patient has since continued on the combination therapy of ortho-k plus RLRL. He has been compliant with the three minutes, twice-a-day treatment, which is reported digitally to the clinic (Fig 4). OCT measurements did not show any loss of vision or damage to the retina.

Fig 4. Patient one’s compliance chart

Case study two: single-vision distance and RLRL

Patient two was referred to us in December 2023, aged 11.75 years. She had previously been prescribed clear single-vision distance (SVD) spectacles but was referred to us for myopia management. She had refraction of:

- OD: -0.75/-0.25 x 90

- OS: -0.75/-0.50 x 87

- Axial length: R 23.92, L 24.06

- Choroidal thickness: 213μm

- Visual acuity: 6/6

It was quite early in her myopia journey. In October 2023, the referring clinic had recorded OCT scan results of R 23.91mm, L 23.86mm. But when she was first examined at our clinic, six or seven weeks later in December 2023, an OCT scan showed progression which was significantly more pronounced in the left eye at R 23.92mm, L 24.06mm. This is a good example of why SVD spectacles are often not a good prescription for myopes because they can have stable levels of myopia but experience significant axial length changes which will continue if untreated. After consultation with the parents, it was decided to try RLRL.

Fig 5. Patient two’s axial length graph

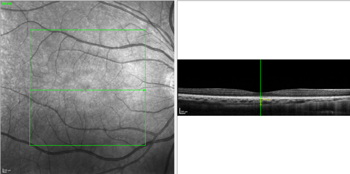

At her follow-up visit in January 2024, there was no change in the left eye but a slight reduction in axial length in the right eye, with the scan recording R 23.87mm, L 24.06mm. Five weeks later, at her second follow-up, her scan showed a slight reduction in the right eye and a more significant reduction in the left eye at R 23.85mm, L 24.00mm (Fig 5), with an increase in choroidal thickness from 213μm to 236μm (Figs 6 and 7). Since then, the patient has continued using the Eyerising device with good compliance (Fig 8) and has reported no side effects.

Figs 6 and 7. Patient two’s choroidal thickness pre-treatment (top) and at two-month follow-up

Fig 8. Patient two’s compliance graph

Case study three: Miyosmart and RLRL

Patient three was a seven-year-old from Perth who was under co-management with our clinic. She had been prescribed Miyosmart spectacles in Perth and had refraction of:

- OD: -1.00 DS

- OS: -1.75 DS

- Axial length: R 23.77mm, L 23.98mm (taken in Perth in August 2023)

- Choroidal thickness: 241μm

- Visual acuity: 6/6

In December 2023, the patient was examined in our clinic and axial lengths of R 23.86mm and L 24.13mm were recorded. When plotted on a Tideman trend graph, taking into account the patient was a seven-year-old Caucasian female, these measurements indicated we could expect to see a significant increase in axial length in the next two years with an increased risk of high myopia in adulthood (Fig 9). We prescribed RLRL therapy, which the patient began the next day.

Fig 9. Patient three’s comparison with Tideman trend graph

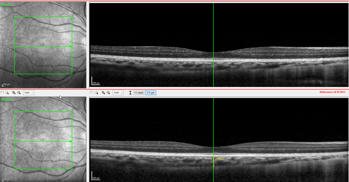

At her follow-up appointment three weeks later, in January 2024, the OCT scan showed an increase in choroidal thickness from 241μm pre-treatment to 274μm, with a reduction in axial length in both eyes, which was significant in the right eye at R 23.8mm, L 24.1mm (Figs 10 and 11).

Figs 10 and 11. Patient three’s choroidal thickness pre-treatment (top) and at one-month follow-up

Since then, the patient has returned to Perth where she continues to use the Eyerising device with good compliance (Fig 12) and has reported no side effects.

Fig 12. Patient three’s compliance graph

Compliance rates

In general, we achieve very good compliance rates with the Eyerising device because it notifies the clinic and parents if sessions are missed. So, unlike lens and atropine use, we are not relying on the patient’s self-reporting.

Compliance is typically calculated as the percentage of recommended treatment time that a patient actually uses the device. Patients need to use the device twice a day, for five days in every rolling seven days. Therefore, within each seven-day period the patient should receive 10 treatments. For example, patient three started her treatment on 11 January. Her treatment records for the following three weeks show how often she used the device: 11/01-17/01: 10 times; 18/01-24/01: eight times; 24/01-31/01: six times. So patient three’s January compliance rate is calculated as: 24 uses / (21/7 x 10) x 100 = 80%.

Conclusion

Like many other myopia therapies, we still aren’t sure exactly how RLRL works, but it could be associated with choroidal thickness change, potentially remodelling the sclera. The treatment appears to stimulate blood flow in the retina, with one theory being it stimulates the mitochondria, where the cells’ energy is created. RLRL may do this by increasing the transportation of electrons, oxygen consumption and levels of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), helping to thicken the choroid and thus slow the rate of axial length growth and control myopia progression.

Using OCT, we are confident we have seen reduction in axial length, but at this stage we cannot claim causal effect, since all the patients are using ortho-k or other kinds of lenses and there are many other factors that can affect choroidal thickness and axial length. What we can say is that about one-third of the decrease in axial length is the result of choroidal thickening, which I suspect scleral remodelling partly accounts for. It has been postulated that the thickening might be due to inflammation (which is why we are investing in the FLIO module, to look for any signs of inflammation) but we have seen no indication of it to date. Beyond that, the next step would be a multifocal electroretinogram.

In my experience, not only does the safety profile of RLRL compare very well with most treatment options, with the exception of glasses, it actually seems to be better tolerated and has fewer side effects. There is certainly no risk of infection or corneal abrasion, for instance.

At the moment, RLRL is an adjunct therapy and I don’t think it will ever be a standalone treatment, with the possible exception of prophylactic use for high-risk younger children. My experience supports it being most useful as an adjunct to ortho-k as that allows the patient to be glasses-free during the day with very good control of progression, which I believe could potentially be full control.

Had you asked me 15 years ago whether we would ever be able to have full control of myopia, I would have said probably not, but with the combination of ortho-k and RLRL therapies, I believe we are now very close.

Jagrut Lallu is co-owner and a senior optometrist at Rose Optometry in Hamilton, New Zealand, a clinical senior lecturer at the Deakin School of Optometry in Melbourne, Australia, and founder of the New Zealand Eye Research Centre. He has a special interest in irregular cornea, corneal disease and ortho-k, including hyperopia, astigmatism and myopia control.