Female hormones and the ocular surface

An optimum balance of hormones is required to maintain tear film integrity and ocular surface health. These hormones, particularly in women, can be responsible for the development of dry eye disease (DED), but interestingly can also be used in DED treatment.

Insulin-like growth factors, sex hormones, hypothalamic-pituitary hormones, glucocorticoids, growth hormones, insulin and thyroid hormones are all essential hormones for supporting ocular surface health. The female body undergoes various changes to its chemical balance that may also affect the ocular surface throughout life – from puberty, menstruation cycles, contraceptive use, pregnancy and, ultimately, to stages of menopause. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT), in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and other assisted-reproductive therapies can further cause hormonal imbalance that may result in a disrupted ocular surface.

Oestrogen and progesterone are present at the ocular surface and in the tear film. Even though both the female sex hormone, oestrogen, and the male sex hormones, androgens, interfere with lipid secretion from meibomian glands1, DED is reportedly more common in women at various stages of life. Higher DED prevalence is noted during pregnancy, lactation, contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy use, ovariectomy and diseases, including premature ovarian failure, androgen insensitivity syndrome, sex steroid hormone dysfunction and polycystic ovarian syndrome2, 3.

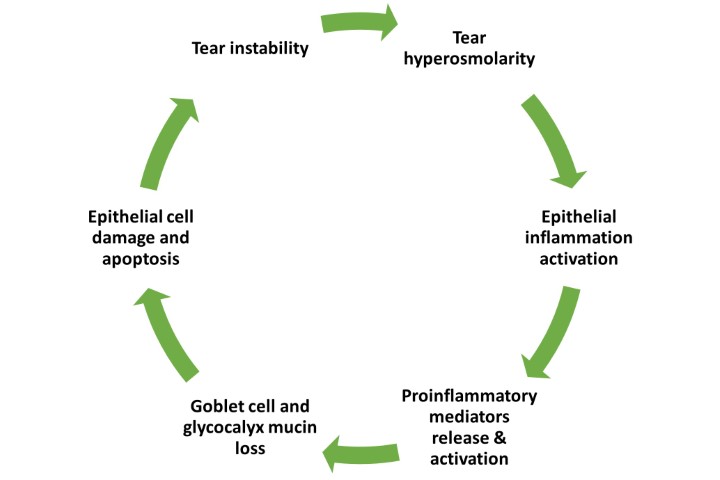

Significant subjective discomfort symptoms and objective DED signs, together with several biochemical, physical and psychological changes are noted during regular menstrual cycles. These changes may be exacerbated by pre-existing conditions including underlying DED, diabetes or clinical depression. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, inflammatory changes are driven by the low level or absence of progesterone in the lacrimal gland. Simultaneously, a peak in oestrogen reverses these changes and prompts lacrimal secretion4. An increased level of ocular discomfort is noted in the ovulation phase. Accelerated maturation of conjunctival epithelial cells and reduced goblet cell count result in poor mucin supply for the tear film4.

Several environmental and lifestyle factors also affect the ocular surface throughout the follicular phase, however further research is needed. Seemingly, physical exercise and increased caffeine intake can improve tear quality during the ovulation phase5. The lower levels of progesterone and oestrogen in the luteal phase affect the ocular surface but conflicting reports of worsening and improving DED symptoms around this time have been reported. Clinicians are therefore encouraged to advise patients, especially young women, to be mindful of lifestyle choices that may affect their ocular surface on a daily basis.

Commencement of perimenopause and menopause impact skin and ocular function significantly, as they do the rest of the body. Oestrogen and androgen receptors are identified in various parts of the eye, including the conjunctiva, cornea, meibomian glands, iris, retina and choroid6. After menopause, serum oestrogen levels are influenced by leakage from various peripheral tissues and might not reflect the oestrogen levels on the ocular surface6. Although the general notion of worsening dry eye in postmenopausal women exists, there remains a paucity of clinical data in the literature. The effects of oestrogen on the ocular surface cannot be viewed independently, but rather need to be considered in the context of other sex hormones, particularly androgens. Androgens support lacrimal gland function, and androgen deficiency is commonly noted during menopause, so tends to drive higher rates of DED in women in their fifties. The fundamental challenge though, is to differentiate changes secondary to hormonal imbalance from those of the normal ageing process.

Women not only experience a higher frequency and severity of DED, but also a greater impact of DED in their everyday lives compared to men6. It’s important to recognise that women tend to visit GPs more often than they do optometrists or ophthalmologists, thus GPs may be more likely to be the first to record any dry eye symptoms during a patient’s annual or regular visits and can assist patients by making an ophthalmic referral. Eyecare practitioners are encouraged to liaise with GPs to promote timely diagnosis for patients and plan appropriate treatment strategies.

This article features highlights from Dr Stuti Misra’s research paper ‘Influence of hormones on the ocular surface in health and disease in females’, written to fulfil the requirements of becoming an American Academy of Optometry (AAO) Diplomate in cornea, contact lens and refractive technology. According to the AAO, only 1% of optometrists worldwide have reached the Diplomate milestone.

References

1. Suzuki T, Schirra F, Richards S, Jensen R, Sullivan D. Estrogen and progesterone control of gene expression in the mouse meibomian gland. IOVS. 2008;49(5):1797-1808.

2. Smith J, Vitale S, Reed G, et al. Dry eye signs and symptoms in women with premature ovarian failure. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(2):151-156.

3. Yavas G, Ozturk F, Kusbecı T, et al. Meibomian gland alterations in polycystic ovary syndrome. Curr Eye Res 2008;33(2):133-138.

4. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. Apr 2007;5(2):93-107.

5. Sullivan D. Tearful relationships? Sex, hormones, the lacrimal gland, and aqueous-deficient dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2004;2(2):92-123.

6. Sullivan D, Rocha E, Aragona P, et al. TFOS DEWS II sex, gender, and hormones report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):284-333.

Dr Stuti Misra is an optometrist-scientist and senior lecturer within the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Auckland and an AAO Diplomate. Her research interests include anterior segment imaging, ocular surface diseases, corneal innervation, diabetic eye disease and community eye health.