Hindsight: the quest is history…

Picking up the phone that day was akin to picking up the loose end of a ball of wool the cat had played with. The 73-year-old woman on the other end of the line was very agitated and emotional as she described the perils of looking through an “oil bubble” and how her poor vision was restricting her life. Her anxiety was also related to her relationship with her partner, who she feared would leave her because of her blindness and total dependency.

She had seen a telescope attached to spectacles on the internet and on contacting her optometrist as to where she might acquire such a device, he had given her my number. The mention of an oil bubble indicated this appeared to be a case of retinal detachment. This was confirmed by the trail of emails that followed, providing enough history for me to unravel what was going on.

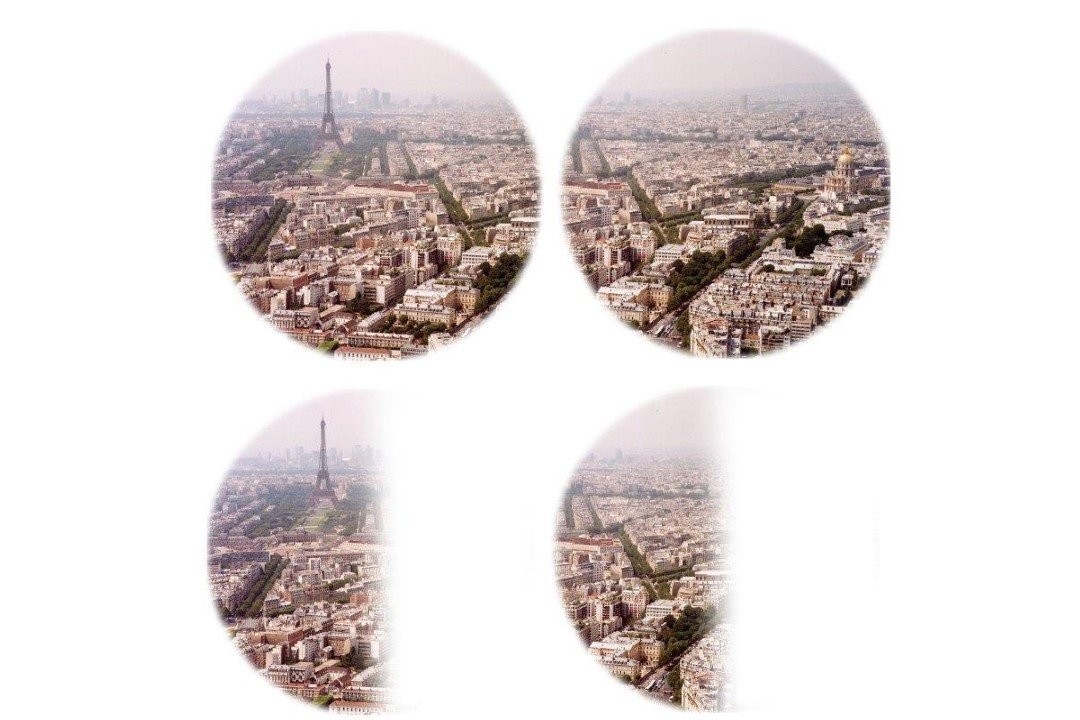

After right-eye cataract surgery in 2009, she’d been able to see very well, she said, but subsequently had suffered a retinal detachment in that eye, which was repaired with a silicone oil tamponade. This was removed a month later, when further surgery to repair the retinal detachment was required and the oil tamponade was replaced. She now wears spectacles to compensate for long-sightedness, but these do not correct her vision because, “where the oil mixes with the eye fluid, it creates cloudiness”. Her left eye she said was ‘blind’ and therefore she was forced to look through this cloudy oil.

When I saw her, she walked in wearing spectacles of prescription: (RE) +6.00 -0.75 x 80, (LE) +4.50 DS. I assumed this was a near prescription as the last distance refraction reported by her optometrist had been: (RE) +1.75 -1.00 x 85. (LE) balance. There appeared to be little difference in her distance vision with or without her glasses, but she felt better wearing them.

She also told me she’d recently realised she could use the camera on her phone to act as a zoom lens. I asked her to show me how she used it and was not surprised to find she held the phone up to her glasses, in front of her left lens, but looking over her glasses with her left eye unaided. Her left eye, therefore, was obviously not ‘blind’, just myopic. The +4.50DS spectacle lens must be a balance lens, probably since she had cataract surgery.

Finding the forgotten eye

I was able to discern the rest of her history from her optometrist. She was originally an RGP contact lens wearer with a refraction of: (RE) -16.50 -0.75 x 90, VA 6/18-, add +2.50; (LE) -13.00 -1.25 x 90, VA 6/60+, add +2.50. She had previously had acuity of 6/7.5 each eye with her RGP lenses.

At some stage, the acuity of her left eye with a contact lens in place had dropped to 6/60, probably as a result of cataract, forcing her to use her considerably more myopic right eye until that required cataract surgery, and subsequently suffered a retinal detachment. The whole history became very confusing at that point. There was so much emphasis on saving the vision in the right eye that it appeared the left eye, and her ability to function on a day-to-day basis, had been forgotten.

She’d been relying on her right eye for a few years. So when she took her contact lenses out for cataract surgery, she’d not put her left one back, delighting in her new, unaided distance vision. Nobody thought to suggest otherwise, so the left eye was written off as ‘blind’.

I put her full 2007 prescription for the left eye into a trial frame and gave it to her. But she immediately rejected it. Later, she admitted, she was so shocked at how much she could see, even though it all “looked a bit weird”, that she had torn the trial frame off in panic. Her binocular near acuity using her spectacles was less than N80 on a high-contrast single-word chart in average room lighting. This improved to N16 using her unaided left eye alone and to N10 with intense local light.

I discussed the reasons for needing a balance lens in her left eye and why, at present, without a contact lens in her left eye she was unable to use both eyes together. There remained the option of refitting the left eye with a contact lens, but I pointed out she would be unable to read or see her telephone by looking over her glasses with her naked eye, but she may be able to see better overall using both eyes together with reading glasses. I suggested she speak to her optometrist about her options, which included cataract surgery in the left eye.

The patient purchased several optical and non-optical aids to assist her with daily tasks and she went off with a great deal to process, while I compiled a report for her optometrist.

How brave of her!

Soon after, I received a report from the patient’s surgeon saying he had recently met her to discuss the various options to maximise the potential of her left eye. It was decided to do left cataract surgery with a target refraction that would approximate her right eye’s acuity, leaving her about +2.00 hyperopic. He had made her aware of the risks, given her history, the dense cataract and high myopia.

The operation went well and she told me she no longer needed the small video-magnifier that she had purchased from me and wanted to return it as a donation for someone else who might need it. She then bought a duplicate small, self-illuminating pocket magnifier that she’d found very useful for shopping and other spot-reading tasks.

The take-home message

It’s important to consider not only how to fix the immediate problem in front of you, but how the patient is going to function visually in their environment as a result of the change that is about to be made.

The other important factor was the patient’s loyalty to her optometrist over many years and his excellent record-keeping which enabled me to tap into her history and piece together the long journey that had led to this confusion and misery. Had I not known she’d had a previous acuity of 6/7.5 in her left eye, I might have believed she was blind. Ultimately, that history and the communication between colleagues resulted in a positive outcome for her from her simple but desperate cry for help.

Sadly, we seem to have lost the benefits of long-term relationships with all our healthcare professionals, be they doctors, dentists, or optometrists. The family doctor is nearing extinction and it horrifies me that people today just hop into the nearest emergency medical clinic or place selling fancy frames and see a different practitioner every time. Chair-hopping patients lose sight of the value of clinical history and relationships because they don’t know any better. When it comes to medical problems, there is more to long-term relationships and access to history than meets the eye.

Naomi Meltzer is an optometrist who runs an independent practice specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.