It’s just a pterygium… or is it?

A pterygium is a benign, triangular, fibrovascular growth extending from the bulbar conjunctiva over the limbus and onto the cornea (Fig 1)¹. Pterygia are common, with world prevalence reported as 12% in a systematic review in 2018². A pterygium is an acquired proliferative disorder (rather than a degenerative one) due to ocular surface irritation that can occur in one or both eyes of patients – typically those who have been living in sunny countries. Ultraviolet radiation exposure, wind and dust, and viral infections are thought to abnormally activate fibroblasts and induce invasive properties, resulting in pterygia³. The exact pathogenesis, however, remains unclear.

Management of a pterygium

Asymptomatic pterygia do not need any active treatment. Ultraviolet light protection is recommended for all patients, but especially those patients with pterygia, to prevent them worsening. Good-fitting, wrap-around sunglasses, according to the AS/NZS 1067.1:2016 standards, along with wide-brimmed sunhats should provide adequate protection against ultraviolet light. Notably, manufacturers and importers in New Zealand are not required to follow this standard (unlike Australia, where it was made mandatory in 2017), so practitioners and patients alike should be aware that not all tinted glasses will provide adequate UV protection.

Some pterygia may cause signs and symptoms of ocular irritation without causing visual impairment. Pterygia can distort the natural tear distribution over the ocular surface, resulting in sensations of dryness, itchiness or burning. These symptoms can be alleviated with ocular lubricants. Patients with inflamed pterygia in whom lubrication is insufficient can be prescribed topical steroids like fluoromethalone 0.1% used up to four times a day for one to two weeks. Steroids should be used sparingly and cautiously with close follow-up to monitor for possible corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension/glaucoma and assess the patient’s response to treatment.

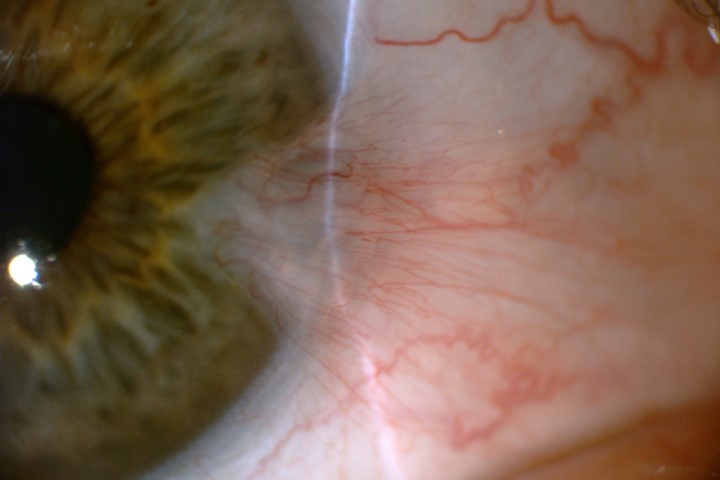

Fig 2. A lesion suspicious for OSSN due to lobulated structure showing abnormal vessel pattern (left) and lissamine green staining (right). Credit: Dr Mo Ziaei

Pterygia which cause visual impairment or ocular discomfort will likely benefit from surgical intervention. Larger pterygia can physically reach the central visual axis, while others can distort the vision by inducing corneal astigmatism, specifically a flattening of the cornea in the meridian of the growth of the pterygium. Patients requiring cataract surgery with such pterygia should ideally have pterygia removed first, and the cornea should be allowed to settle before proceeding with cataract surgery to prevent distorted biometry.

The most common surgical technique in New Zealand for primary pterygium removal is a simple excision with a free conjunctival autograft from the superior bulbar conjunctiva. In patients with extensive pterygium or with co-existent glaucoma, amniotic membrane transplantation may be used instead or as an adjunct to the conjunctival autograft. In exceptional cases where corneal involvement is significant, laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) may be needed to regularise the cornea.

Pterygia which are a cosmetic concern can benefit from surgical intervention. However, the referral criteria for publicly funded pterygium surgery can vary nationwide, so referrers should review local guidelines. Private insurance companies typically have broad criteria for funding surgery and usually approve the reimbursement following a consultation with a specialist.

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia

Part of the finesse in managing pterygia is being able to differentiate benign pterygia from other more serious lesions, such as malignant ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) or other masqueraders of pterygia. This can occasionally prove challenging.

OSSN can range from mild dysplasia to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Compared to pterygia, lesions suspicious for dysplasia can look more gelatinous, leukoplakic, papilliform or plaque-like and can be more vascularised (presence of a feeder vessel or abnormal blood vessel patterns). Other tests that may help the clinician differentiate between a benign or malignant lesion include the use of Lissamine green staining (Fig 2) or anterior segment OCT examination. There is an abrupt transition from normal epithelium to thickened hyperreflective epithelium in patients with OSSN⁴.

Typical steps of a simple pterygium excision and conjunctival free autograft. Credit: Dr Mo Ziaei

OSSNs are managed differently from pterygia. OSSNs are excised usually with a no-touch technique with 4-5mm margins with alcohol epitheliectomy to the cornea and application of cryotherapy to the surgical margins⁵. This can be accompanied by adjuvant topical interferon or mitomycin C therapy to prevent recurrence. At the severe end of the disease spectrum, aggressive and recurrent disease can be vision-threatening, requiring exenteration, or even life-threatening from invasive metastases⁶. For this reason, it is important to be cautious with atypical or suspicious lesions that may be masquerading as pterygia.

Several studies have examined the retrospective incidence of OSSN in samples sent for histopathological diagnosis of suspected pterygium, with rates varying from between 0.3%⁷ and 0.6%⁸ in studies from North California and London to 9.8% in a survey from Brisbane⁹.

There is an increased incidence of OSSN in countries with more exposure to ultraviolet radiation like New Zealand. A prospective New Zealand study based in Hamilton found that 10% of conjunctival and corneal samples sent for histopathology were positive for OSSN. The authors calculated the regional incidence of OSSN in 2020 to be 3.67/100,000/year¹⁰, which is on par with some African countries like Zimbabwe¹¹. Other than exposure to ultraviolet radiation, older age, fair skin pigmentation and being immunocompromised are all factors associated with increased risk of OSSN.

With the relatively high incidence of OSSN in New Zealand and possible difficulty identifying dysplasia clinically (five of the 18 histopathologically confirmed OSSN had a pre-op diagnosis of pterygia or pinguecula in the Hamilton study), it could be argued that all corneal and conjunctival specimens excised as possible pterygia should be sent to the pathology laboratory for histopathological confirmation.

When to refer a pterygium

For the practising optometrist, we recommend referral of any pterygium that is rapidly increasing in size, is recurrent, has atypical features (especially in patients with higher risk factors for OSSN) or has typical features but impacts vision.

References

- Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology (9th edition), p198.

- Rezvan F, Khabazkhoob M, Hooshmand E, Yekta A, Saatchi M, Hashemi H. Prevalence and risk factors of pterygium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep-Oct;63(5):719-735.

- Shahraki T, Arabi A, Feizi S. Pterygium: an update on pathophysiology, clinical features, and management. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2021 May 31;13:25158414211020152.

- Mejía L, Zapata M, Gil J. An unexpected incidence of ocular surface neoplasia on pterygium surgery. a retrospective clinical and histopathological report. Cornea. 2021 Aug 1;40(8):1002-1006.

- Habibalahi A, Allende A, Michael J, Anwer A, Campbell J, Mahbub S, Bala C, Coroneo M, Goldys E. Pterygium and ocular surface squamous neoplasia: optical biopsy using a novel autofluorescence multispectral imaging technique. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Mar 21;14(6):1591.

- Ditta L, Shildkrot Y, Wilson M. Outcomes in 15 patients with conjunctival melanoma treated with adjuvant topical mitomycin C: complications and recurrences. Ophthalmology. 2011 Sep;118(9):1754-9.

- Modabber M, Lent-Schochet D, Li J, Kim E. Histopathological rate of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in clinically suspected pterygium specimens: 10-year results. Cornea. 2022 Feb 1;41(2):149-154.

- Quhill H, Magan T, Thaung C et al. Prevalence of co-existent neoplasia in clinically diagnosed pterygia in a UK population. Eye 37, 3757–3761 (2023).

- Hirst L, Axelsen R, Schwab I. Pterygium and associated ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009 Jan;127(1):31-2.

- Hossain R, Oh J, McLintock C, Murphy C, McKelvie J. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a 12-month prospective evaluation of incidence in Waikato, New Zealand. Vision (Basel). 2022 Aug 12;6(3):50.

- Reynolds J, Pfeiffer M, Ozgur O, Esmaeli B. Prevalence and severity of ocular surface neoplasia in African nations and need for early interventions. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2016 Oct-Dec;11(4):415-421.

Dr Himanshu Wadhwa is a RANZCO trainee registrar working at the Greenlane Clinical Centre in Auckland.

Dr Mo Ziaei is a cataract, anterior segment and refractive specialist working at the Greenlane Clinical Centre and Re:Vision Laser & Cataract in Auckland.