Māori and Pasifika, and ophthalmology

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) has identified indigenous workforce development as a priority. Tackling this in New Zealand, Dr Simone Freundlich, the current Maurice and Phyllis Paykel corneal and anterior segment clinical research fellow at the University of Auckland, and Auckland-based ophthalmologist and RANZCO Māori and Pasifika Committee chair Dr Will Cunningham led a research project analysing Māori and Pasifika graduate interest in ophthalmology.

Published earlier this year in Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, the study involved a number of ophthalmologists, researchers and medical students from Otago and Auckland Universities and the Auckland District Health Board¹. It was overseen by Auckland University’s head of ophthalmology Professor Charles McGhee.

The research

The main purpose of the research was to identify factors which could be used to improve the representation of indigenous ophthalmologists in New Zealand. A total of 954 medical graduates (from 2012 to 2017) were asked to rank their medical specialty training in order of preference. Only 6.7% ranked ophthalmology in their top-three preferred training specialties and six (9.3%) of those 64 graduates, compared to 14.6% of the total cohort, identified as Māori or Pasifika heritage.

At first glance, the 6.7% who ranked ophthalmology in their top-three preferred training specialties seems like a very small number but this is the expected rate, said Prof McGhee, as ophthalmology is a specialist area, typically attracting around 15 to 20 applicants for just four to six training posts in New Zealand each year. Also, not all graduates in the survey answered the question as many do not make up their minds about which discipline to pursue until after they graduate, he said.

The key finding, however, is that of the small percentage who ranked ophthalmology in their top three, an even smaller percentage of those were of Māori/Pasifika heritage.

Why is this a problem?

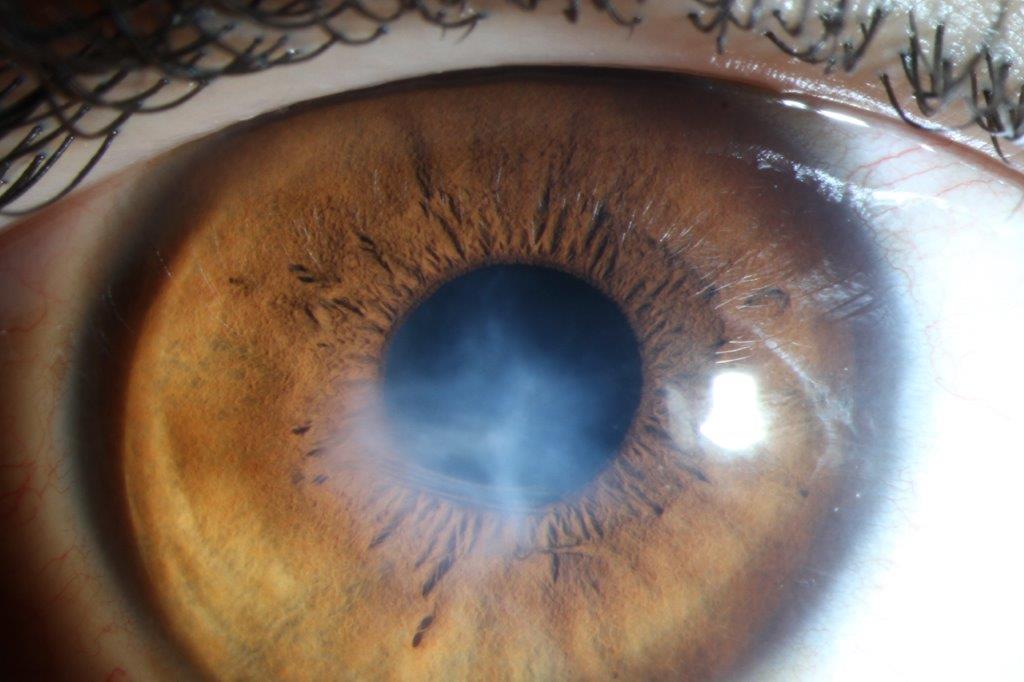

We are frequently told that compared with the general population, Māori and Pasifika experience poorer health outcomes and this includes a range of ophthalmic conditions, such as diabetic eye disease, retinopathy of prematurity, keratoconus and advanced cataracts¹.

In the study’s introduction, the authors said, “Disparities in indigenous health outcomes are multifactorial, impacted by historical and current societal pressures, as well as interactions between indigenous and non-indigenous populations including health professionals². Culture has a significant impact on the doctor-patient relationship, influencing how patients understand their health, seek treatment, and respond to treatment³.”

Why would having more Māori/Pasifika ophthalmologists change this outcome?

There’s been a recognition over recent years that health professionals should be representative of the populations they serve, said Dr Freundlich. “Having representation within medicine, irrespective of the specialty, urges medical professionals to develop a wider scope of culturally safe practice.

When it comes to patients, irrespective of a doctor’s culture or ethnicity, ophthalmology remains a highly specialised profession that is very culturally diverse, she said. “Obviously, Māori/Pasifika ophthalmologists may, or may not, do things in their day-to-day practice that will change health outcomes for individual Māori/Pasifika patients. However, at a systemic level, more Māori/Pasifika ophthalmologists are crucial to the discussions that are occurring to address inequity in health outcomes for indigenous populations.”

Dr Simone Freundlich

This could include something as simple as being able to converse in their own language which could encourage patients to be more open and communicative, said Dr Freundlich. “For example, in urban environments, such as Auckland, Pasifika clinicians who can speak their native language are well received by Pasifika patients, just as Asian clinicians are well received by Cantonese, Mandarin or Hindi speaking patients. Equally so, in regions where Te Reo is more widely incorporated and spoken, Te Reo-speaking medical professionals are well received by Māori patients.”

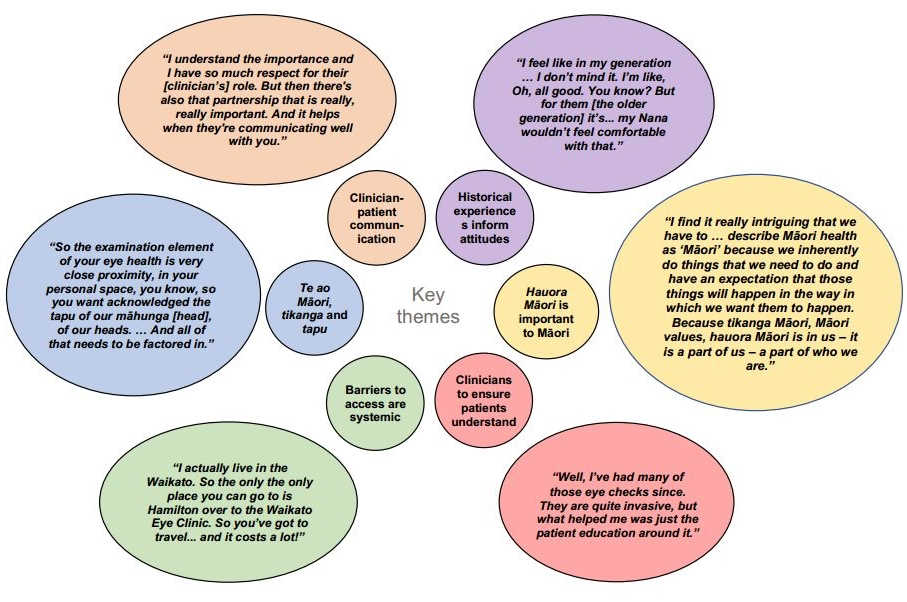

Why do medical graduates choose ophthalmology?

The research involved semi-structured interviews with open questions that explored influencing factors such as exposure to ophthalmology, the training pathway, lifestyle factors, family (whanau) and cultural factors that might influence a medical graduate’s choice of ophthalmology. No significant differences in influencing factors between Māori/Pasifika and non-Māori students were identified. Qualitative interviews with Māori/Pasifika graduates, however, highlighted positive experiences with ophthalmology but limited exposure overall as a factor, though some cited negative anecdotes and unclear training pathways as discouragements.

The most surprising finding was the limited knowledge of ophthalmology as a specialty. Opportunities to talk to ophthalmologists or those who are currently training at undergraduate level could address this and is already in progress, said authors. RANZCO is also supporting junior indigenous doctors interested in ophthalmology through research, such as the RANZCO Trevelyan-Smith Scholarship Fund.

Dr Freundlich is the 2018 recipient of this grant and is also of Māori, New Zealand European and German ancestry, with whanau connections to Tainui (Waikato) and Ngapuhi (Hokianga). She graduated through the Māori and Pacific programme at the University of Auckland and credits the mentoring by Dr Will Cunningham, Dr Rachael Niederer and Prof McGhee for her choice of sub-specialty.

“Culture has significant impact on the doctor-patient relationship, influencing how patients understand their health, seek treatment and respond to treatment,” wrote the study authors. Asked to elaborate on this idea, Dr Freundlich said, “Irrespective of whether it is Māori culture or any culture, we must all appreciate that culture shapes our world view, including how we interact with each other, how we engage with our communities and society as a whole, and also how we respond to our health.

“New Zealand, like many other countries, utilises a western model of medicine. However, as a nation we are very multicultural. So, it is exciting to see that medicine is starting to recognise certain beliefs and customs of both tikanga Māori (Māori customs) and Pacific peoples as we build more inclusive models of health incorporating language, whanau connections and broader influences.

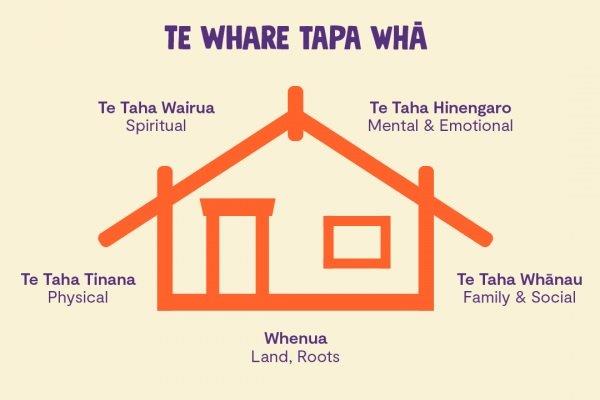

“Engagement with Māori has resulted in all of us furthering our understanding of these influences and the development of models of health, such as Te Whare Tapa Whā and Te Pae Mahutonga (see box below).”

For example, in traditional Māori culture and customs (Tikanga) the head is considered tapu or sacred, said Dr Freundlich. “However, I don’t believe this means that Māori will not seek treatment for their eyes. When specific permission is asked, and the individual treated with respect the head can be touched by eye care professionals.”

Conclusions

As well as identifying that Māori/Pasifika graduate interest in ophthalmology training was low and the importance of providing better specialty exposure and mentor development, the study also found that promoting Māori/Pasifika connections in ophthalmology and clarifying training pathways could help increase Māori/Pasifika medical graduate interest in ophthalmology.

Achieving a culturally representative ophthalmology workforce in the current population of five million requires approximately 25% of New Zealand ophthalmologists to identify as Māori or Pasifika, concluded study authors. “Improving Indigenous representation within ophthalmology will strengthen our commitment to developing a culturally safe workforce where Māori and Pasifika patients receive care from doctors of all ethnicities, with respect for the unique role that culture plays in health.”

There is no direct, follow-up study planned at present, said Prof McGhee, but other aspects of career choice in the undergraduate programme are being worked on, including the opportunity to undertake an ophthalmology-focused BMedSci (Hons) and providing more information on the career pathway at the end of each ophthalmology attachment. “We have also been actively recruiting Māori/Pasifika postgraduates into clinical research fellowships - 20% of appointments in the last two years - in the University of Auckland as a steppingstone into an ophthalmology career.”

RANZCO’s role in bridging the gap in NZ

The RANZCO Leadership Development Program (LDP) is an 18-month programme which aims to build leadership and advocacy skills amongst RANZCO fellows, support ophthalmologists who work for the greater good of the community and ophthalmology as a profession, and to develop the next generation of ophthalmic leaders. As part of this programme, Dr Cunningham presented the findings of the study in a presentation entitled, Identifying factors that encourage or deter Māori and Pasifika doctors from pursuing formal ophthalmology training in New Zealand. This inspired Dr Cunningham to chair the RANZCO Māori and Pasifika Committee, a diverse group consisting of ophthalmologists, many of whom identify as Māori and/or Pasifika, RANZCO officials and cultural advisors.

The committee has established relationships with other indigenous organisations, including Te ORA, representing Māori medical students and practitioners, and LIME (Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education) and will continue to seek out and engage with Māori and Pasifika as both groups and individuals, said Dr Cunningham. One major focus of the committee is to develop the Māori Action Plan that looks to address and improve ophthalmic health equity for Māori in Aotearoa by developing genuine partnerships with Māori, improving access to ophthalmic healthcare and Māori representation within ophthalmology, and championing further research that specifically addresses ophthalmic health inequity. The Māori Action Plan will also provide a blueprint for the Pasifika Action Plan which is still to be developed.

Dr Will Cunningham

Dr Cunningham, who is also of mixed heritage, including Samoan and European, said he is proud to champion the Māori Action Plan. “RANZCO acknowledges Māori as Tangata Whenua and our obligations as Te Tiriti o Waitangi partners. As part of our treaty obligations we must include Māori participation in healthcare. Eye care for Māori by Māori.” The aim is to launch this plan in 2021, he said.

References

- Freundlich S, Connell CJW, McGhee CNJ, Cunningham WJ, Bedggood A, Poole P. Enhancing Māori and Pasifika graduate interest in ophthalmology surgical training in New Zealand / Aotearoa: Barriers and opportunities. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology May 2020

- Ellison-Loschman L, Pearce N. Improving access to health care among New Zealand’s Māori population. Am J Public Health 2006; 96: 612-7.

- Medical Council of New Zealand. Strategic plan from 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018. Wellington: Medical Council of New Zealand, 2017. Accessed June 2019. Available from: https://www/mcnz.org.nz/assets/Publications/Straegic-Plans/89db2393bf/Strategic-Plan-2017-2018.pdf

Naomi Meltzer has worked in optometry for more than 30 years. She runs an independent optometry practice specialising in low vision consultancy in Auckland and is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.

Māori health models

Te Pae Mahutonga, depicted using the Southern Cross constellation and guiding stars (Durie, 1999)

Te Whare Tapa Whā

The four cornerstones (or equal sides) of Māori health in the Te Whare Tapa Whā model of health are: whānau (family health); tinana (physical health); hinengaro (mental health); and wairua (spiritual health). Should one of the four dimensions be missing or in some way damaged, a person, or a collective may become ‘unbalanced’ and subsequently unwell. For many, Māori modern health services lack recognition of taha wairua (the spiritual dimension). In a traditional Māori approach, the inclusion of the wairua, the role of the whānau (family) and the balance of the hinengaro (mind) are as important as the physical manifestations of illness.

Te Pae Mahutonga

Te Pae Mahutonga (the Southern Cross star constellation) brings together elements of modern health promotion. The four central stars of the Southern Cross represent four key tasks of health promotion: mauriora (cultural identity); waiora (physical environment); toiora (healthy lifestyles); te oranga (participation in society). The two guiding stars, acting as prerequisites for health promotion, are ngā manukura (leadership) and te mana whakahaere (autonomy).

Source: The Ministry of Health website, www.health.govt.nz. Model developed by Sir Mason Durie, psychiatrist and former professor of Māori studies at Massey University.