Openness and candour – the road to a culture of safety

The title of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency’s (AHPRA’s) latest Taking Care podcast*, ‘Openness and candour – a road to a true culture of safety’, was intriguing. Its introduction mentioned the need for much greater openness and honesty between health practitioners, their patients and patients’ families, especially when things go wrong.

Sue Sheridan, a founding member of Patients for Patient Safety (a World Health Organisation initiative) US network, led the Taking Care discussion on what is meant by duty of candour, secondary harm and a patient-centric culture of safety in a medical and paramedical environment. Joining her were Peter Walsh, CEO of UK charity Action Against Medical Accidents, and Australian health lawyer Michael Gorton, who chaired an expert working group on the State of Victoria’s Statutory Duty of Candour obligation.

Firstly, some definitions. ‘Candour’ means being frank and sincere with what is being communicated, the quality of being open and honest; ‘secondary harm’ is what can occur over hours or weeks after the initial (primary) injury; a ‘primary victim’ is the patient suffering the alleged injury or unanticipated outcome of some form of medical treatment; and a ‘secondary victim’ is someone who suffers injury as a result of the one suffered by the primary victim.

Patient-centric culture prioritises strategies and practices that create positive experiences for patients through communication, services and outcomes. It’s the opposite of the perception held by some current healthcare professionals and organisations that patients are separate components of the healthcare system – the healthcare professional designs, delivers and improves health services, while the patient (the ‘consumer’) receives them.

One would think that candour, openness and a patient-centric culture of safety would be the obvious route to positive outcomes in a medical organisation, but if they were, countries and states wouldn’t feel the need to introduce legislation to this effect. This includes Victoria’s statutory duty of candour, whose introduction was confirmed in 2021, and the UK’s Duty of Candour Amendment, which came into force in 2014. In the podcast, Sheridan talks candidly about her own experiences with secondary trauma experienced by her family, which led to her advocating for greater medical candour.

Culture of safety in healthcare (not to be confused with cultural safety or cultural competence, which is to acquire skills and knowledge of other cultures) is the extent to which an organisation or individual supports and promotes patient safety. It refers to the values, beliefs and norms shared by healthcare practitioners and other staff that influence their actions and behaviour. It determines behaviours that are rewarded, supported, expected and accepted, and it exists at all levels within the organisation.

When there is a lack of leadership or a lack of openness and engagement, things go wrong! The flipside of this is that even when things go wrong, if there is openness and honesty it can be massively healing for everyone and secondary harm is often dissipated. By definition, a culture of safety means that the patient’s and family’s view are included in the process of reaching a satisfactory outcome.

Radical candour

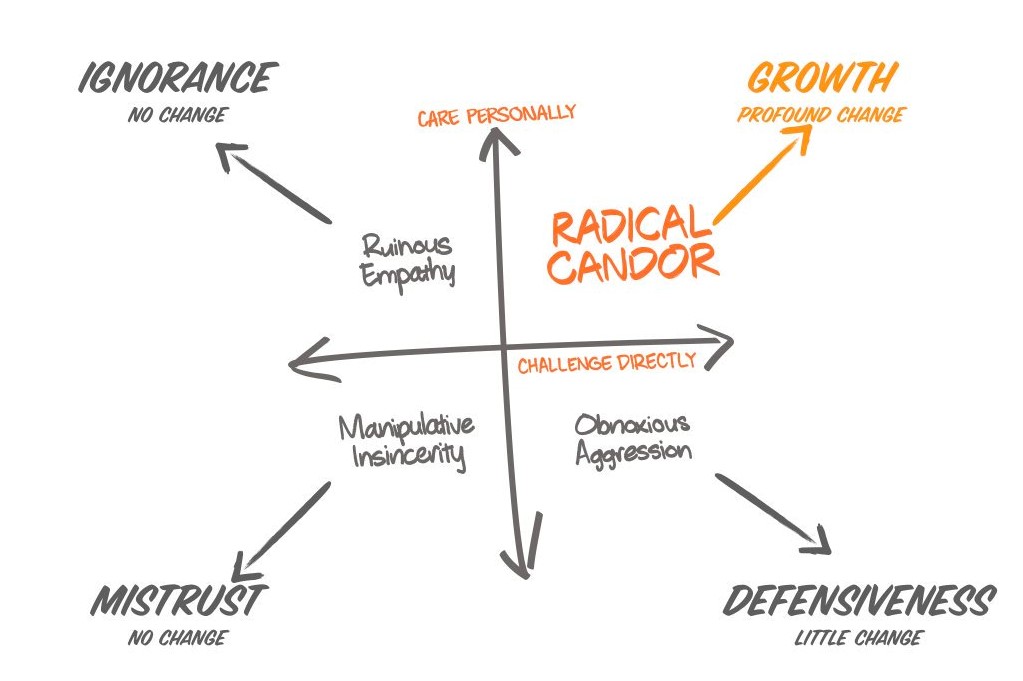

Radical candour (Fig 1), the subject of Apple and Google executive Kim Scott’s bestselling book of the same name, is about being humble, helpful and immediate; or as the book’s strapline puts it, ‘caring personally while challenging directly’. If it’s criticism, it should be in-person and in private, while praise should be in public. It considers not only what we are communicating, but also how it is communicated and with whom.

Fig 1. Radical candour, as defined by Kim Scott

Victoria’s Statutory Duty of Candour is a legal requirement to be open and honest with patients or their families, when something goes wrong that appears to have caused (or could have caused) significant harm. Its main principles are:

- Tell the patient (or patient’s family, whānau, advocate) when something has not gone to plan

- Apologise to the patient

- Offer an appropriate remedy or support to put matters right (if possible)

- Explain fully to whoever needs to know the short- and long-term effects of what has happened

- Offer a plan to avoid a similar situation happening to others. This is often what patients appear to value most

The duty of candour also extends to employer organisations and encourages a learning culture by reporting incidents leading to harm as well as near misses. It also reduces passing the buck or bullying, particularly when there is a requirement to involve the whole team.

Closer to home

Victoria’s Statutory Duty of Candour will come into force in November 2022. It follows an earlier amendment to the Health Services Act 1988 to improve transparency in the state’s health system. The amendment also introduced legal protections around health services, which means that apologies and internal reports cannot be used in a court of law but will be available to patients or their family or carers.

In the podcast, Gorton pointed out that more candour and openness has been shown to result in less litigation and better outcomes for everyone. “Lawyers come in after the event if there is cover-up and no information,” he said. “Compensation still occurs, but less than if litigation is involved. Doctors’ own insurance companies tend to agree with this.”

A cynic might wonder if this is just a mechanism to avoid litigation, the fear of which has always been a barrier to sharing information within a medical organisation, let alone with a patient. But insurers are now starting to recognise that litigation is less likely when candour is used than if patients felt there was a cover-up. As yet, there is no follow-up research available to help understand the long-term effects on patients and their families, however.

Where’s the protection for health practitioners?

It appears that in Australia the duty of candour will only apply to organisations, not individual healthcare practitioners. A culture of litigation assumes negligence and malpractice, whereas a culture of candour assumes that no medical practitioner or institution sets out to cause harm but sometimes things happen that create undesirable outcomes. These may be patient-related factors, systems failures or human errors.

In the UK, where the duty of candour was introduced in 2014 for England and Scotland, covering health organisations, doctors, nurses and other healthcare practitioners, things are better for having an increased culture of openness, said Walsh. “It is not entirely fixed. There are still cover-ups and ‘economies of truth’, but candour is more the norm. Before the Statutory Duty of Candour, the conversation would not be had. Previously the system did not frown on cover-ups but encouraged it. This empowers health professionals to do what comes naturally to them and takes away incentives to make complaints and litigate.”

Speaking to The Irish News in September 2021, however, the British Medical Association’s Dr Tom Black was less positive, saying the new legislation when expanded to individuals in Northern Ireland would compel doctors to admit care failings or risk prosecution and would victimise staff. “To explicitly bring in legislation linked to criminal sanctions does seem to us an extraordinarily punitive reaction to a situation which is calling for more openness and a learning culture where people can talk openly about the problems they have.”

Kiwis’ candour attitude

The situation in New Zealand is somewhat different. We have the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) – a no-fault, government-indemnified system where victims injured as a consequence of ‘medical misadventure’ receive compensation. In exchange for the certainty of compensation, ACC legislation waives the right of patients to sue clinicians. Has this non-fault system provided a strong incentive for medical practitioners and organisations to voluntarily assume a duty of candour?

Some legal commentators suggest the ACC system provides minimal incentives to practitioners to take care, allows poor standards to go undetected and disincentivises the collection of information which would guide institutions towards designing better systems. According to Bristol University’s Professor Oliver Quick, writing in the Medical Law Review, “The overall effect has been to shift risks that would otherwise be borne by practitioners and administrators onto the very people the ACC system was designed to protect – individual patients.” No-fault systems may be effective in delivering compensation to victims but are efficient only if the effects of reduced incentives to exercise care can be adequately offset by effective monitoring, enforcement and education mechanisms, he said. This may be the legal view, but it does not address the secondary-harm issue.

It also all seems very focused on surgical outcomes. So what is its relevance to the eyecare professions? As an optometrist, I thought this wouldn’t have any application. Then I found a ‘duty of candour annual report’ from a UK optometry practice, which appeared to address an NHS requirement. It included fields to describe aims and objectives of the practice, adverse events and remedial actions taken, and lessons learned as a result. Is this where we are heading in New Zealand – more pointless meetings and paperwork, or an opportunity to reflect on our behaviour and learn from the experience?

I recently heard of a young woman who, following retinal detachment surgery, told all her colleagues how traumatising it was to discover she now faced further surgery for cataract removal in that eye. Her main gripe was that nobody had warned her it was a possible consequence of her first surgery. What is the secondary harm here – that she feels she hasn’t been adequately communicated with, or that she will go into her second surgery with anxiety and negative attitudes that further harm may result? Perhaps the pre-surgery communication could have been better, or perhaps the patient didn’t take in what was communicated. Certainly, the priority of the surgical team would likely have been to get on with the sight-saving retinal surgery.

In such a scenario, the duty of candour would require a meeting with the patient and any significant others to candidly communicate that although the outcome of a cataract after retinal surgery would not have changed, the communication of this possibility prior to surgery could have been improved upon and then assure them steps would be taken to improve this in the future.

The patient’s right not to know

There is a whole area of medical ethics that the duty of candour seems to ignore – some people just do not want too much information, particularly before a procedure when they are feeling vulnerable. In the age of genetic testing being more advanced and more accessible, some people are kicking back at family members (and occasionally medical professionals) who disclose knowledge of which they would have preferred to remain blissfully ignorant.

Since listening to this podcast and exploring this topic, I’ve found myself viewing every personal, family member’s and friend’s bad experience with the medical professions through a duty of candour lens. It brings up a bevy of emotions! But I am also a healthcare professional, so this same lens can skew my view of what is reasonable patient expectation and how much radical candour is reasonable to expect from a medical team when lives, livelihoods and mental health are at stake.

It takes courage to confront one’s own fallibility, less so to change the environment that encourages a culture of blame. Perhaps by changing the culture to one of openness and candour, the road to safety will be smoother and shorter.

*www.ahpra.gov.au/Resources/Podcasts.aspx