Prevalence of DED in young adults – current understanding and management

The prevalence and severity of dry eye disease (DED) is known to increase with age1. However, several recent studies have reported a high prevalence in younger populations. Increased digital screen use, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, has been associated with symptomatic DED in 70.8% of university students; other associated risk factors were higher perceived stress scale scores, prolonged contact lens wear and female sex2.

Even prior to the pandemic, studies were reporting higher than expected DED prevalence in young adults. Data obtained from a large population-based cohort study in the Netherlands found a particularly high prevalence of dry eye symptoms in 20-30-year-olds3. They proposed an association with hand-held screen use among the younger adults in the cohort. A similar trend was found in a large paediatric population (7-12-year-olds), where smartphone use was strongly associated with DED, whereas outdoor activity was protective against its development4.

The prevalence rates of DED vary between studies, depending on the diagnostic clinical test, type of questionnaire, or cut-off values employed. In 2016, 44.3% of Ghanaian undergraduates reported symptomatic dry eye in a cross-sectional study5, while in 2018 a lower prevalence of clinically diagnosed DED (10%) was reported among 901 university students from Shanghai6. In a large cross-sectional study, 2140 Brazilian university students reported a higher prevalence of dry eye symptoms than the general 40-years-old-plus population7. In addition to well-established risk factors, sleeping less than six hours and use of a screen for more than six hours a day were found to be associated with DED. A higher prevalence of DED has also been reported in Asian than Caucasian populations1.

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), a contributor to evaporative DED, is considered to be the leading cause of dry eye in clinic and population-based studies8. Use of digital devices has been linked to meibomian gland loss and reduced or incomplete blink rates9, which are known risk factors for evaporative DED10.

Aston’s young adult study

As yet there appear to be few studies exploring the prevalence and associated risk factors specifically for evaporative DED in young adults. For this reason, a prospective two-year study involving 50 young adults is underway at the Optometry School, Aston University, UK. The study aims to compare lifestyle, ocular symptoms, ocular surface signs and tear inflammatory biomarkers in a young adult cohort with different severities of evaporative dry eye, with healthy age-, gender-, and ethnicity-matched controls. For the study, DED was diagnosed on the basis of a positive symptom score and one or more clinical signs (tear instability, hyperosmolarity or ocular surface staining) according to the TFOS DEWS II diagnostic criteria. Those failing to meet the criteria were designated non-DED.

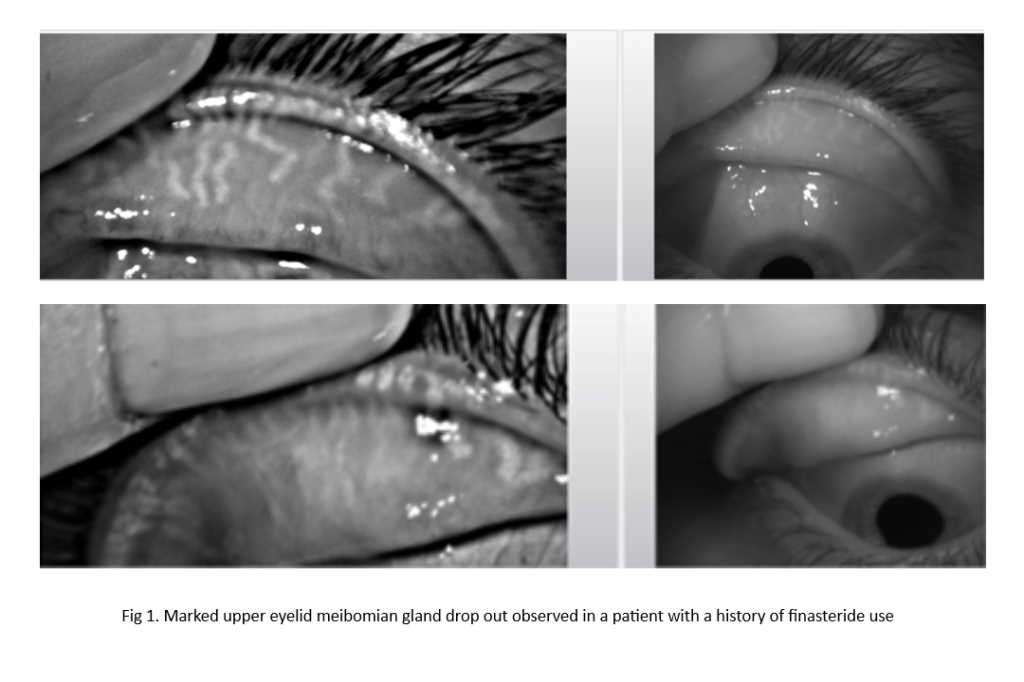

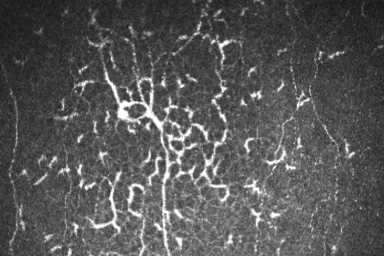

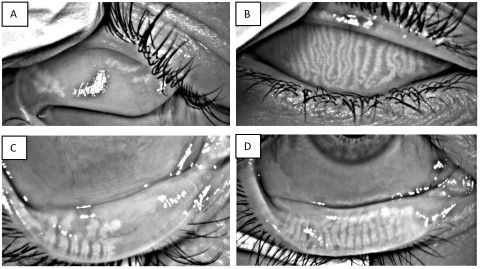

Fig 1. Upper and lower lid meibography of two young study participants. Images A and C show significant meibomian gland loss in a participant with evaporative DED. Images B and D are from a non-dry eye participant showing no major gland loss.

Interim analysis indicates a mean age of 19.9±1.6 years across the sample, with 72% of participants being female. First-year data analysis comparing DED and non-DED participants did not find significant differences in composite meibography scores, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) positive tests, screen hours and lifestyle scores. Also, no correlations were found between screen hours, non-invasive tear breakup time, composite meibography scores and MMP-9 results.

However, it has been noted that 82% of the non-DED group displayed one or more positive signs of ocular surface disease, while 48% of participants were found to have at least 25% meibomian gland loss in one or other eyelid. Only two non-DED participants had no gland loss at all. The final results of this study will be available in 2023.

Conclusion

Longitudinal and cross-sectional DED studies have largely focused on older age groups. Studies monitoring DED in young adults over a longer period are needed. While current treatment and management is heavily aligned with strategies employed in older populations, limited information is available on differential DED treatment for the young population. In addition to traditional first-line treatments, they can be counselled for the key modifiable risk factors such as screen-use habits, sleeping habits, contact lens use, diet, blinking patterns, outdoor activities and management of stress levels.

The upcoming TFOS Workshop ‘A Lifestyle Epidemic: Ocular Surface Disease’, chaired by Professor Jennifer Craig, will discuss these in detail.

References

- Stapleton F, et al, TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul Surf, 2017. 15(3): p. 334-365

- Tangmonkongvoragul C, et al, Prevalence of symptomatic dry eye disease with associated risk factors among medical students at Chiang Mai University due to increased screen time and stress during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One, 2022. 17(3): p. e0265733

- Vehof J, et al, Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye in 79,866 participants of the population-based Lifelines cohort study in the Netherlands. Ocul Surf, 2021. 19: p. 83-93

- Moon J, K Kim, N Moon, Smartphone use is a risk factor for pediatric dry eye disease according to region and age: a case control study. BMC Ophthalmol, 2016. 16(1): p. 188

- Asiedu K, et al, Symptomatic Dry Eye and Its Associated Factors: A Study of University Undergraduate Students in Ghana. Eye Contact Lens, 2017. 43(4): p. 262-266

- Li S, et al, Ocular surface health in Shanghai University students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol, 2018. 18(1): p. 245

- Yang I, et al, Prevalence and associated risk factors for dry eye disease among Brazilian undergraduate students. PLoS One, 2021. 16(11): p. e0259399

- Craig J, et al, TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf, 2017. 15(3): p. 276-283

- Wolffsohn J, et al, Demographic and lifestyle risk factors of dry eye disease subtypes: A cross-sectional study. Ocul Surf, 2021. 21: p. 58-63

- Portello J, M Rosenfield, C Chu, Blink rate, incomplete blinks and computer vision syndrome. Optom Vis Sci, 2013. 90(5): p. 482-7

Rachel Kathryn Casemore is an optometrist and third-year PhD research candidate at Aston University, supervised by Dr Dutta and Professor James Wolffsohn.

Dr Debarun Dutta is a tenured lecturer at the Optometry School, Aston University, UK. He is responsible for both excellence in research and teaching in the area of ocular surface and contact lenses.