Stevens-Johnson syndrome and the ocular surface

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a rare and serious disorder that can cause painful blisters and lesions on the skin and mucous membranes. It has a significant impact on the eye and many excellent articles on this disease can be found in the literature. Over the years, I have managed numerous patients with this condition, both adults and children.

SJS can lead to health issues that profoundly affect the physical, emotional and social wellbeing of patients. It has two phases, each of which warrants a different approach, and I’ve found it impossible to separate the ocular impact from the general impact in my patients. For successful treatment, collaboration is key – a multidisciplinary approach and a strong collegiate network is invaluable for looking after SJS patients.

The acute phase

Early recognition and appropriate and prompt management can be lifesaving. Pattern recognition is essential as SJS can often mimic several conditions in its initial stages. The typical history is these patients have been treated for conjunctivitis or upper respiratory tract infections in the emergency department or community first. Occasionally they may have been diagnosed with having had an adverse drug reaction. A skin biopsy often helps clinch the diagnosis. This usually shows full-thickness dermal necrosis without immunoglobulin deposition.

My first step is to flush the surface of the eye with saline. Invariably pseudomembranes need to be cleared using a cotton tip applicator; their removal can be particularly distressing for children. My preferred management is hourly, high-quality preservative-free lubricants, ointment, with topical steroids introduced six-hourly. I use topical antibiotics only where there are signs of corneal infection.

The patients I have dealt with were in the ICU, being treated like burn victims. I have found children exhibit more pronounced conjunctival and corneal involvement, often leading to long-term visual impairment, so I am more aggressive in my management of younger patients. If the disease has stabilised with no signs of progression after 24 hours, I then continue for a further 24 hours. If the disease has continued to progress despite treatment, I use an amniotic membrane graft as it promotes healing and reduces inflammation and scarring. This is particularly effective when applied early. It is, however, difficult in an ICU and the use of a contact-lens-based amniotic membrane is a helpful adjunct. The contact lens may also limit the mechanical friction associated with the swollen ulcerated eyelids.

The chronic phase

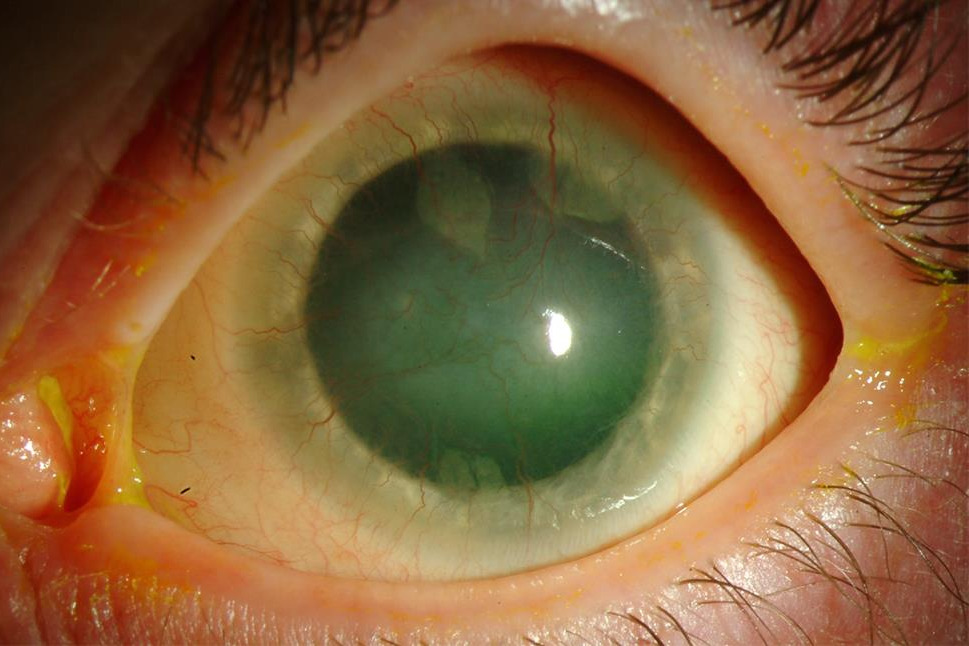

The loss of the mucous-producing goblet cells results in long-term severe dry eye disease. Loss of limbal stem cells, essential for corneal healing, results in corneal neovascularisation, scarring and reduced vision. In children this can precipitate amblyopia. Limbal stem cell transplantation is usually hampered by the fact that there is insufficient limbal stem cell tissue in the fellow eye as it too is often severely affected.

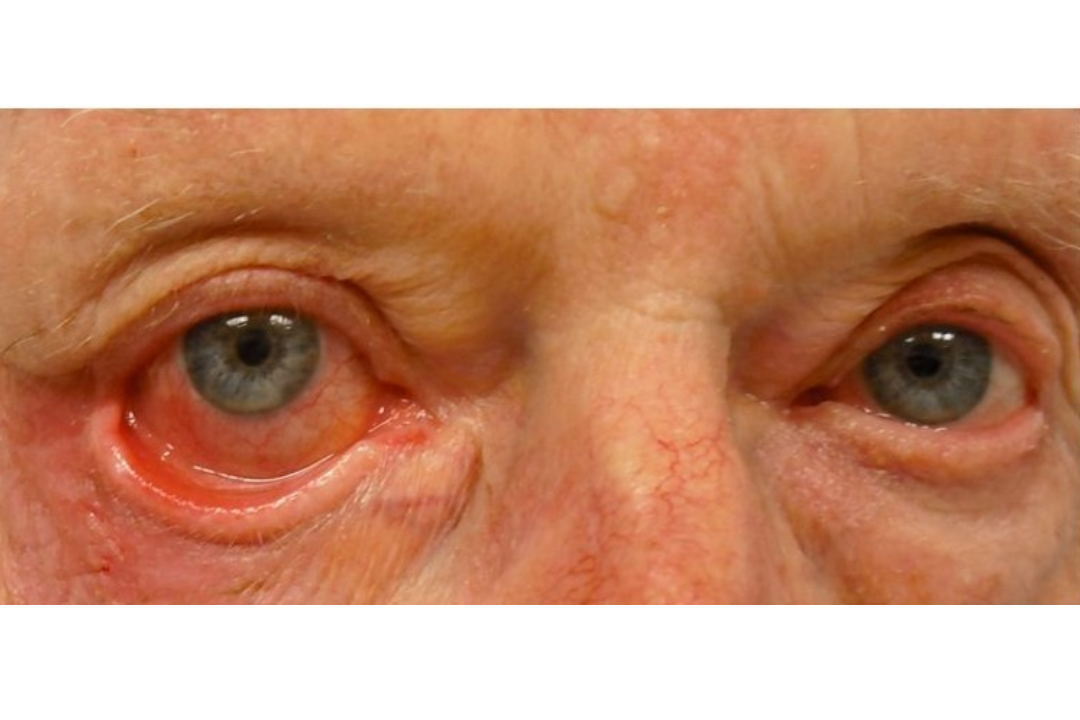

Conjunctival changes result in symblepharon formation which, if not prevented, can cause long-term pain on eye movement, restricting eye mobility. Eyelid entropion and trichiasis increase the mechanical friction at the ocular surface and need to be dealt with surgically. These are patients you get to know on a first-name basis as they need regular monitoring.

You need to be aware of the psychological impact of severe ocular disease, which can be profound in children. Fear, anxiety and depression may result from the painful and disfiguring nature of the disease and its treatments, so psychological support and counselling are essential components of care. Strategies to improve compliance include involving parents and caregivers, using age-appropriate communication and possibly sedating young children for certain procedures such as electrolysis of trichiatic lashes. Compliance with ongoing topical preservative-free lubricants or serum eyedrops is critical.

Frequent medical visits and potential long-term treatments can disrupt work and school. Changes in physical appearance alter the way these patients act socially; this is exacerbated by the chronic pain and fatigue often associated with SJS. I have seen these patients become withdrawn and isolated. Rehabilitation services and educational programmes are available; however, early and effective management of acute episodes and long-term complications are important as these can mitigate some of the physical and emotional burdens.

Dr Colin Parsloe is a Rotorua-based ophthalmologist and a clinical advisor to the New Zealand Dry Eye Association who is passionate about helping fellow dry eye disease sufferers.