The complex diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma

Intraocular lymphoma (IOL) comprises a heterogenous group of malignant lymphocytic neoplasms arising from either within the central nervous system as a primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) – a subset of primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) – or outside the central nervous system (CNS) as a metastasis from a non-ocular neoplasm (secondary intraocular lymphoma)1. In PIOL the lymphoma cells are confined only to the eye, with no evidence of spread to the brain or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), although concomitant and subsequent intracranial involvement is common2. Almost all cases of PIOL are reported to be B-cell type in origin and fall within the category of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, with fewer cases being of T-cell origin3.

The mean age of presentation for PIOL is in the fifth and sixth decades of life, although cases in children and adolescents have been reported. It shows no racial predilection but has a reported sex bias, with some studies showing women are twice as likely as men to be affected4. Incidence of the disease seems to be increasing, for reasons unknown but thought to include our increasing life expectancy and an increase in the use of systemic immunosuppressive drugs3,4.

An IOL diagnosis is difficult to reach, as discussed further below, but it is crucial to do so in a timely manner as it is both a sight- and life-threatening condition requiring prompt treatment.

Clinical presentation

Diagnosing PIOL represents a challenge for eye specialists as it can masquerade as chronic posterior uveitis, including a good initial response to steroid treatment. It is vital, therefore, to have a high degree of clinical suspicion.

A recent meta-analysis found that PIOL generally begins with one eye, with more than half progressing to bilateral involvement5. Up to 20% of PIOL cases will already have CNS involvement at the time of diagnosis, with progression to CNS involvement in a further 58% over the disease course5.

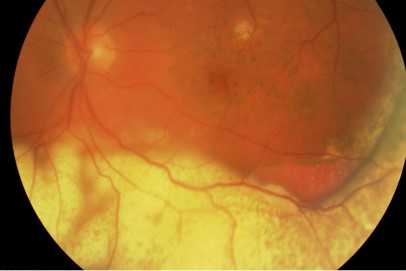

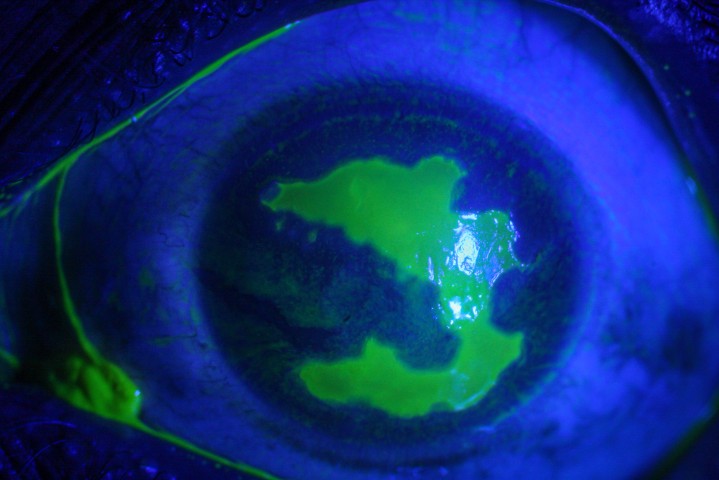

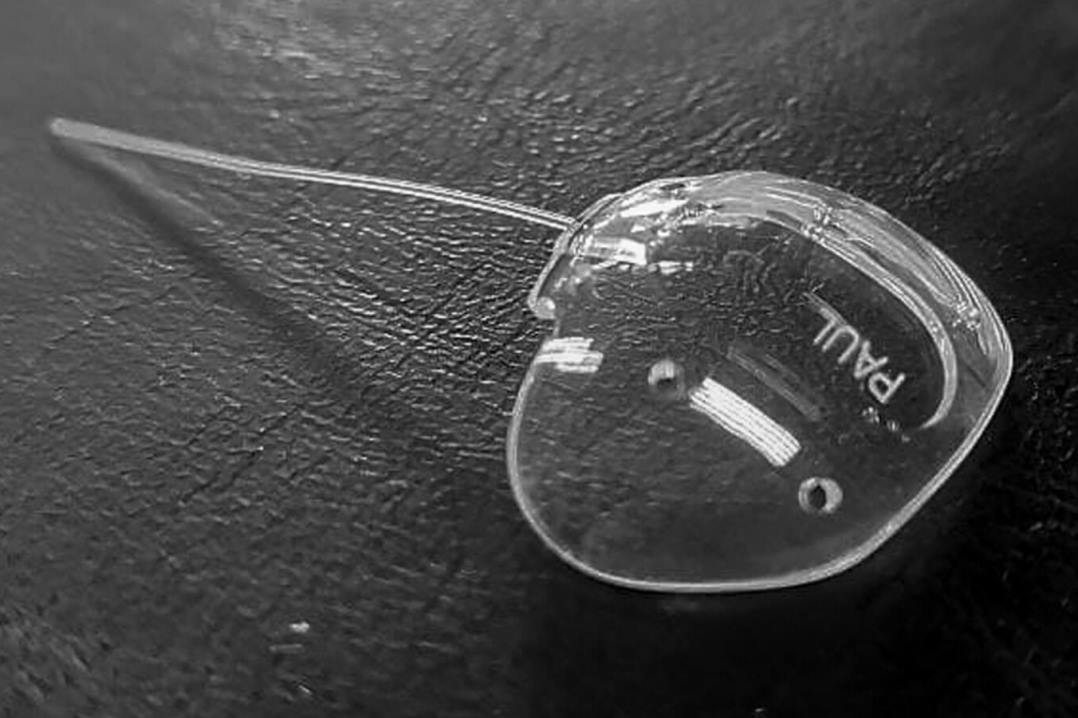

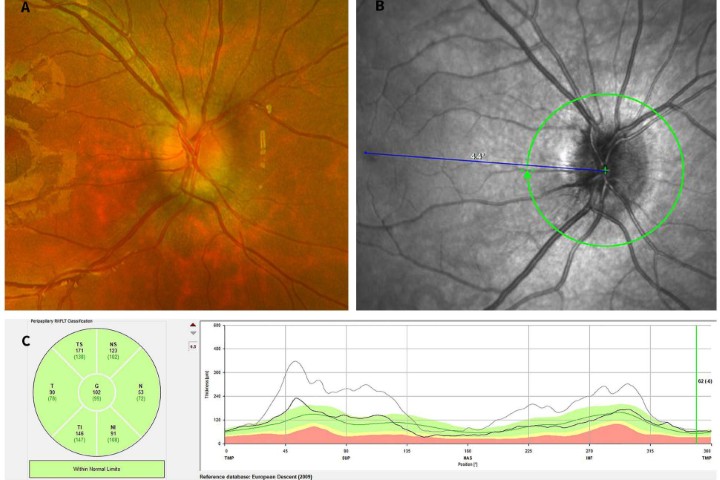

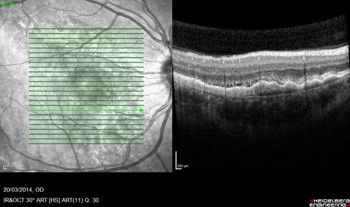

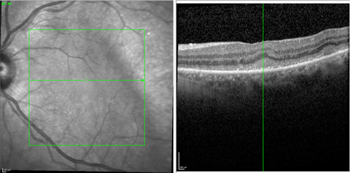

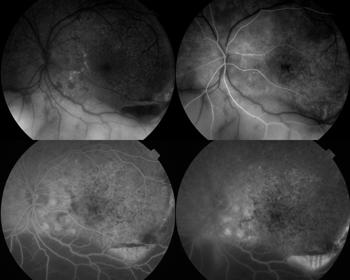

It typically presents with relatively non-specific symptoms of blurred vision, floaters and reduced visual acuity (although this is often well maintained initially)4. The most common clinical signs on examination are vitreous opacity (Fig 1), fine keratic precipitates and retinal or subretinal infiltration (Fig 2)5. Vitritis is present in the majority of cases and there may be clumps, sheets or strands in the vitreous with mild to moderate haze. The characteristic ‘leopard skin’ appearance of lymphomatous retinal lesions arises from the development of creamy lesions with orange-yellow infiltrates lying deep to the retina or RPE (Fig 3, top)4. Cystoid macular oedema is often absent in PIOL, which is an important differentiating sign from cases of uveitis with a similar degree of vitreous inflammation5.

Further investigation

Given that PIOL is a masquerade syndrome that mimics myriad other conditions, the mainstay of initial blood testing will involve ruling out these conditions, particularly infectious cases of uveitis such as tuberculosis, syphilis and toxoplasmosis. Other causes often considered are sarcoidosis and white dot syndromes. HIV testing is recommended to check for unknown immunodeficiency4.

The gold-standard diagnostic test is that of histologic and immunochemical confirmation via a tissue sample and, once PIOL is suspected, it is important to organise an urgent vitreous biopsy to confirm diagnosis. Unfortunately, this can be difficult and false negative results are common due to rapid cell degeneration within samples, too few cells within a sample or the presence of other cells and debris making it more difficult to identify the lymphoma cells6. If the vitreous sample is negative but the clinical suspicion remains high, proceeding to retinal or chorioretinal biopsy may be considered6.

It is also important to undertake appropriate neuroimaging, ideally contrast-enhanced MRI, to look for any CNS spread. In cases of CNS involvement MRI may show unifocal or multifocal periventricular homogenously enhancing lesions3.

Use of multi-modal imaging

The diagnosis of PIOL is often delayed, with the literature reporting a mean time from onset of ocular symptoms to diagnosis of 40 months7. The most common reason for this delay is initial misdiagnosis, occurring in around half of cases. Delays may also occur due to initial negative biopsy results. Unfortunately, such delays can have a significant impact on patient survival outcomes due to the increased mortality resulting from progression to CNS involvement. The overall survival for PIOL is around 32 months from diagnosis4. However, the prognosis for PIOL is much better in those without CNS involvement compared to those with CNS involvement – two-year survival rate (98% vs 77%); five-year survival rate (97% vs 54%); recurrence rate (20% vs 70%)5. Recent advances in ophthalmic imaging and studies into the characteristic imaging findings in PIOL can help clinicians reduce the time to achieve a definitive diagnosis.

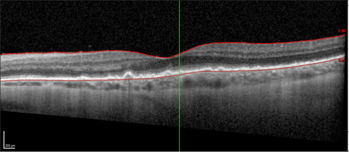

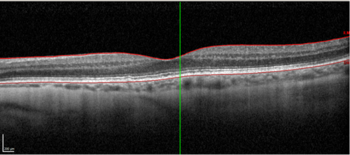

High resolution spectral domain-OCT can be a very effective diagnostic tool in PIOL, with detailed OCT-specific imaging features of PIOL described in several recent studies. Barry et al reviewed 32 eyes with PIOL and noted the presence of hyper-reflective subretinal (53%) and intraretinal (18%) infiltrates, RPE undulation (15%), vitreous cells (15%) and sub-RPE deposits (9%) (Fig 4)8. They also concluded that hyperreflective subretinal infiltrates were an OCT feature unique to PIOL (Fig 5). Xu et al described RPE nodularity (63%) and outer retinal hyperreflectivities (43%)9. The meta-analysis by Zhao et al reported a pooled incidence of 53% for hyperreflective foci in the posterior vitreous; 45% with retinal hyperreflectivity; 37% with subretinal lesions and 34% with intra-RPE lesions5. These OCT features represent functional and structural abnormalities resulting from the lymphomatous cellular infiltration in different layers of the retina – findings which would be unlikely to appear in other ocular inflammatory disease.

The typical fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) finding is of punctate hyperfluorescent defects and round hypofluorescent lesions combining to give a granular pattern (Fig 6)4. This pattern is reversed on fundus autofluorescence (FA), with areas of high autofluorescence on FA corresponding to hypofluorescent lesions on the FFA, with a reported pooled incidence of 91%5.

Treatment

Treatment for PIOL varies widely between centres and remains controversial. Local treatment may include intravitreal methotrexate, intravitreal rituximab, or radiotherapy. Systemic treatment is indicated in the presence of CNS lymphoma with systemic chemotherapy and sometimes radiotherapy too. Some clinicians will elect for systemic treatment even in the absence of evidence of CNS lymphoma, given the high rate of eventual systemic involvement and high mortality. Large randomised controlled trials to guide optimal management are lacking, but the evidence from a recent meta-analysis supported the use of a combination of systemic chemotherapy plus intravitreal therapy as the first-line treatment in PIOL management5.

During treatment, multimodal imaging can be used to monitor success. This includes observing atrophy and resolution of ocular lesions, with no new lesions occurring (Figs 7 and 8).

Conclusions

PIOL presents a diagnostic challenge due to its ability to masquerade as other types of ocular inflammation, which can delay diagnosis and treatment of this sight- and life-threatening disease. A high index of suspicion is necessary in these cases. The identification of key characteristic findings on multimodal imaging can trigger prompt vitreous biopsy and earlier definitive diagnosis and management, leading to better outcomes. OCT in particular is proving to be a valuable tool in the diagnosis of PIOL and for monitoring disease progression and treatment response.

References

- Augsburger J, Greatrex K. Intraocular lymphoma: clinical presentations, differential diagnosis and treatment. Trans PA Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1989;41:796e808

- Chan C, Wallace D. Intraocular lymphoma: update on diagnosis and management. Cancer Control. 2004;11:285-295

- Tang L, Gu C, Zhang P. Intraocular lymphoma. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017 Aug 18;10(8):1301-1307.

- Sagoo, Mandeep S. et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 59.5 (2014): 503–516

- Zhao X-Y et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, management and prognosis of primary intraocular lymphoma. Front Oncol 12 (2022): 808511–808511.

- Hearne E, Netzer O, Lightman S. Learning points in intraocular lymphoma. Eye 35, 1815–1817 (2021).

- Cassoux N, Merle-Beral H, Leblond V, Bodaghi B, Miléa D, Gerber S, et al. Ocular and central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features and diagnosis. Ocul Immunol Infamm. 2000;8(4):243–50

- Barry R, et al. Characteristic optical coherence tomography findings in patients with primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a novel aid to early diagnosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 10 (2018): 1362–1366.

- Xu, Lucy T. et al. Multimodal diagnostic imaging in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Int J Retina Vitr 8.1 (2022): 1–58.

Dr James Brodie is a senior clinical research fellow in uveitis at the University of Auckland and Greenlane Clinical Centre, supervised by Drs Rachael Niederer and Jo Sims, and is a fellow of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

Dr Laura Butler is a uveitis fellow at the University of Auckland, supervised by Drs Rachael Niederer and Jo Sims. Her research and clinical interests also include medical retina.

Dr Rachael Niederer is a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland and consults for Te Whatu Ora Auckland and Auckland Eye in uveitis and medical retina.