The optometrist’s role in inherited retinal diseases

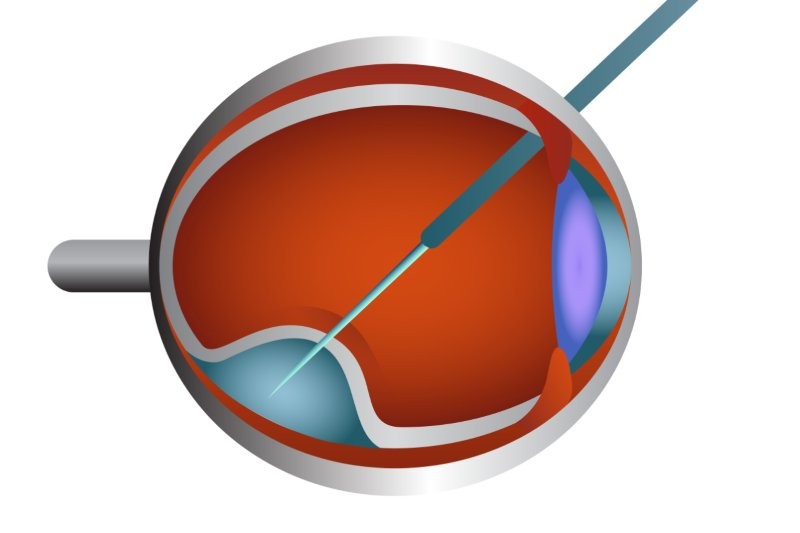

Historically, patients with rare inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) were told there was no treatment to stop them from losing their vision. But this is changing. In 2017, the world’s first ocular gene therapy treatment, Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl), was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for IRDs caused by mutations in the RPE65 gene, causing Leber congenital amaurosis. Gene therapy treatments for at least 20 other IRDs are being developed1 followed closely by stem cell therapies, RNA therapies and optogenetic treatments.

With potential treatments on the horizon, more IRD patients are also able to access genetic testing, reforming historical management. For families with these rare diseases, genetic testing can confirm their diagnosis, identify the correct inheritance pattern and allow accurate genetic counselling, and inform prognosis2. Genetic testing can also identify people with syndromic IRDs who might be at risk of systemic complications, for example heart and kidney disease, who could benefit from early diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, a genetic diagnosis is essential for determining whether a patient is eligible for gene therapy.

Even though significant challenges remain in improving access to new technologies, as primary eyecare providers (ECPs) optometrists are often the first to see IRD patients, so they are well-positioned to give patients informed and measured advice on accessing genetic testing and emerging treatments.

Local knowledge

Our recent survey of more than 700 individuals with IRDs found that over 60% of patients with IRDs did not obtain any information about gene therapy from their optometrist or other allied healthcare providers3,4, highlighting the need to improve the integration of knowledge between clinical care and research.

As part of a project funded by Universitas 21 Health Sciences Group, our team of optometrists, ophthalmologists and researchers at the Universities of Melbourne and Auckland undertook a study to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes and concerns surrounding genetic testing and gene therapy for retinal diseases among ECPs. A survey of more than 500 optometrists in Australia and New Zealand showed they have a high level of interest in genetic testing and gene therapy topics5. Almost all said they thought ophthalmologists should initiate genetic testing, but fewer acknowledged the role of non-ophthalmic clinicians, with 65% saying genetic counsellors and 54% clinical geneticists play a role in initiating ocular genetic testing. This was an important finding, as genetic testing for IRDs is often provided by a multidisciplinary team, where both genetic and ophthalmic specialists work together on diagnosis and providing integrated care for affected families. Comprehensive genetic counselling, before and after testing, is critical for patients to understand their test results, which can have prognostic, systemic, family planning and therapeutic implications.

Approximately 60% of optometrists thought they could play a role in initiating genetic testing for retinal diseases. However, most said they didn’t feel confident discussing genetic testing and gene therapy with their patients. For example, 72% of optometrists said they could, at most, answer a few basic questions about the implications of Mendelian inheritance patterns on family planning and just 14% could describe their local referral pathway for patients to access ocular genetic services.

For optometrists to better support their patients with heritable retinal diseases and be able to initiate discussions about genetic testing and gene therapy, we identified these key areas for education in both foundational and ocular genetics:

- Understanding the reasons for genetic testing for IRDs and possible outcomes. For example, using current sequencing technologies, the likelihood that a genetic test will provide an IRD diagnosis is approximately 60%6

- Being able to acknowledge the differences in genetic testing purposes and strategies for Mendelian conditions, such as rare IRDs, and complex conditions, such as age-related macular degeneration

- Knowing their local genetic testing referral pathways and how patients can access genetic testing

- Understanding the role of genetic providers (eg. genetic counsellors and geneticists) in managing people with IRDs

- Knowing the new treatments being developed for different types of IRDs, where to find information on emerging treatments and clinical trials and how they can refer patients for research.

In collaboration with Retina International, we’re expanding this study internationally to understand clinicians’ perspectives from other regions. It is our hope that by improving education, we can help pave the way for improved collaboration and integrated care between optometrists, ophthalmologists, and genetic care providers to enhance the care and management of families with heritable retinal diseases.

References

- Britten-Jones A, Jin R, Gocuk S et al. The safety and efficacy of gene therapy treatment for monogenic retinal and optic nerve diseases: A systematic review. Genet Med 2021; 24: 521-534.

- Burdon K. The utility of genomic testing in the ophthalmology clinic: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2021; 49: 615-625.

- Mack H, Chen F, Grigg J et al. Perspectives of people with inherited retinal diseases on ocular gene therapy in Australia: protocol for a national survey. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e048361.

- McGuinness M, Britten-Jones A, Ayton L et al. Measurement Properties of the Attitudes to Gene Therapy for the Eye (AGT-Eye) Instrument for People With Inherited Retinal Diseases. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2022; 11: 14.

- Britten-Jones A, Mack H, Vincent A et al. Genetic testing and gene therapy in retinal diseases: Knowledge and perceptions of optometrists in Australia and New Zealand. Clin Genet 2023.

- Britten-Jones A, Gocuk S, Goh K et al. The diagnostic yield of next generation sequencing in inherited retinal diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2022; 249: 57-73.

Dr Ceecee Britten-Jones is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Vision Optimisation and Retinal Gene Therapy units at the University of Melbourne and Centre for Eye Research Australia. An Auckland University optometry graduate, she is currently investigating the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of IRDs and developing outcome measures for gene therapy clinical trials.