The psychological effects of glaucoma and vision loss

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), standard indicators of quality of life (QoL) include physical wellbeing, psychological and mental wellbeing, independence, social functioning, and economic wellbeing. Ocular disease leading to vision loss may affect all of these parameters, significantly impacting a patient’s overall wellbeing and QoL.

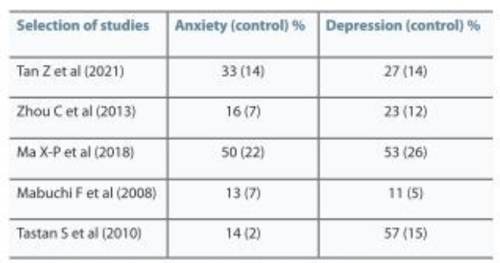

Multiple studies have demonstrated an increased prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients diagnosed with glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and many other vision-threatening ocular conditions1. Table 1 provides a summary of studies reporting on the prevalence of anxiety and depression in glaucoma, with rates generally double that of controls. The psychological effects of glaucoma depend on the timeframe and stage of disease and can vary significantly from initial diagnosis to subsequent stages.

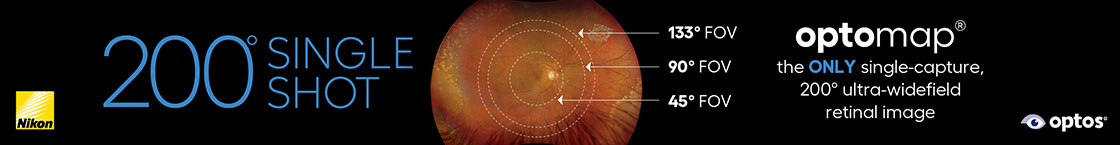

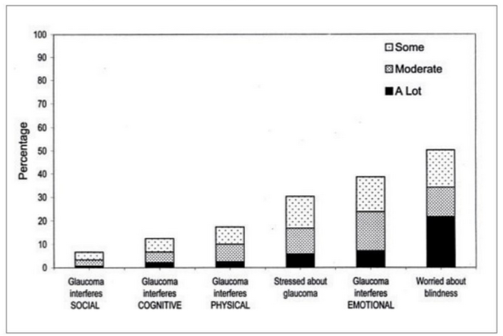

At initial diagnosis, the primary concern reported by patients is ‘fear of blindness’, leading to increased stress, anxiety and depression. In the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS), moderate to severe psychological fear of blindness at time of diagnosis was reported in 34% of patients2. This is demonstrated in Fig 1, along with the other impacts newly diagnosed glaucoma has on QoL parameters. Odberg et al also reported negative emotions in 80% of those newly diagnosed, with one-third of patients in their study reported as afraid of blindness3.

Fig 1. Quality of life in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients (CIGTS)

Factors associated with diagnosis-induced stress include lack of awareness about the disease, misinterpreting the diagnosis as impending blindness and being unaware of the treatment options which can halt the disease2,4. Younger age, female gender and socio-economic status are also associated with increased stress at this stage2,4.

The power of conversation

Evidence suggests patient counselling can make a significant difference. The Glaucoma Australia educational impact clinical trial demonstrated improved glaucoma education and patient knowledge led to a significant reduction in anxiety in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients5. Hence, patients need to be adequately educated about the disease, how treatment is very effective – as well as the importance of adherence and follow-up – and reassured that very few patients develop severe vision loss or blindness.

However, the need for ongoing monitoring and follow-up, lifelong treatment and the possible adverse effects related to this treatment can further contribute to stress. Furthermore, if significant visual field loss develops, this can impede a patient’s ability to work, complete daily activities, participate in sports and hobbies and drive. The latter is one of the most distressing issues for patients, with an occupational driving assessment recommended for those whose vision is borderline for driving.

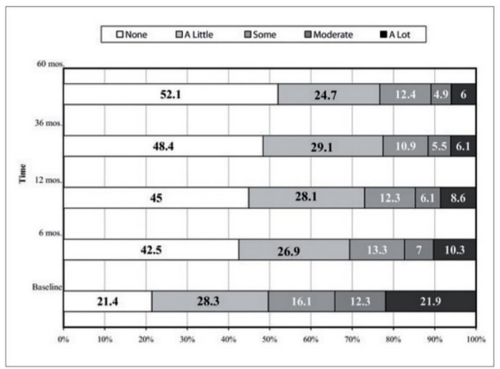

Interestingly, for the majority of patients diagnosed with glaucoma, psychological stress and fear of blindness decreases over time (Fig 2), according to reports from CIGTS2,4,6. The reassurance of regular follow-up and treatment, ongoing stability, better understanding of the disease and the low risk of blindness, adaptation to the diagnosis and the work of support groups such as Glaucoma New Zealand, all contribute to this. Clinicians can further help by using the appropriate level of treatment for the severity of disease, addressing side effects (consider selective laser trabeculoplasty), using the safest and least invasive surgical options and addressing other causes of reduced vision (such as refractive error and cataract).

Fig 2. Fear of blindness decreases over time, as reported in CITGS

For patients who continue to experience stress and fear of blindness, the severity of visual field loss, ongoing progression of disease, pre-existing depression and other co-morbidities are important contributing factors4,6. If severe vision loss or blindness develop, anxiety and depression may be amplified, warranting robust social and psychological support, as well as referral to low-vision services when appropriate. Eyecare professionals can play an important role in the coordination of these services for the patient.

To further complicate matters, studies have demonstrated a strong association between poor adherence to treatment and depression in patients who suffer from chronic diseases7. Several glaucoma-specific studies have also uniformly demonstrated reduced adherence in patients with depression8. Some studies also reported a clinically significant association between anxiety and raised intraocular pressure. In fact, anxiety and depression may even be a risk for progression from a glaucoma suspect to confirmed glaucoma9-10. Hence, a negative cycle can develop between worsening glaucoma, increased anxiety and depression and poor treatment adherence.

Table 1. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in glaucoma

Conclusion

It is important to be aware of the psychological impacts a glaucoma diagnosis and vision loss can have on patients, for many of whom the fear of blindness is significant. Patient education and counselling can go a long way towards easing this psychological stress at the time of diagnosis. It is reassuring that for the majority of patients, however, this psychological stress and the fear or blindness decreases over time. It would be of value to ‘check in’ with your patients from time to time to see how they are coping and arrange referral to appropriate services when necessary.

References

- Mabuchi F, et al. "High prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma." Journal of glaucoma 17.7 (2008): 552-557.

- Janz N, et al. "Fear of blindness in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study: patterns and correlates over time." Ophthalmology 114.12 (2007): 2213-2220.

- Odberg T, et al. "The impact of glaucoma on the quality of life of patients in Norway: I. Results from a self‐administered questionnaire." Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica 79.2 (2001): 116-120.

- Musch D, et al. "Trends in and predictors of depression among participants in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS)." American journal of ophthalmology197 (2019): 128-135.

- Skalicky S, et al. "Glaucoma Australia educational impact study: a randomized short‐term clinical trial evaluating the association between glaucoma education and patient knowledge, anxiety and treatment satisfaction." Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology 46.3 (2018): 222-231.

- Jampel H, et al. "Longitudinal change in mood indicators in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS)." Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 50.13 (2009): 2569-2569.

- DiMatteo R, Lepper H and Croghan T. "Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence." Archives of internal medicine 160.14 (2000): 2101-2107.

- Tsai J. "A comprehensive perspective on patient adherence to topical glaucoma therapy." Ophthalmology116.11 (2009): S30-S36.

- Berchuck S, et al. "Impact of anxiety and depression on progression to glaucoma among glaucoma suspects." British Journal of Ophthalmology 105.9 (2021): 1244-1249.

- Shin D, et al. "The effect of anxiety and depression on progression of glaucoma." Scientific Reports 11.1 (2021): 1-10.

Dr Hussain Patel is a glaucoma and cataract specialist at Eye Surgery Associates and Greenlane Clinical Centre in Auckland. He is also a senior lecturer with the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Auckland.