To ZAP or not to ZAP?

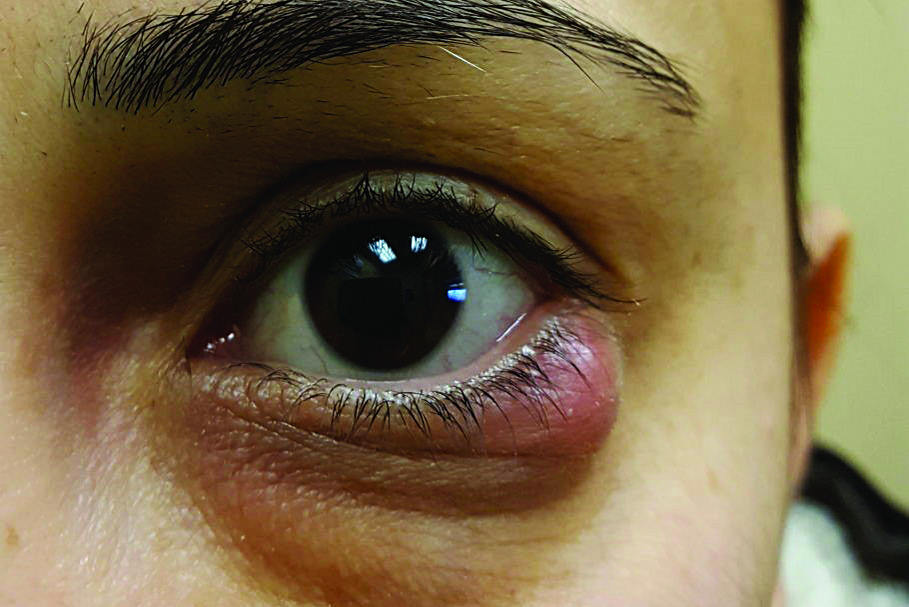

A common incidental clinical finding among optometrists is ‘narrow angles'. That worryingly thin black space on Van Herick assessment alerts us to dust off our gonioscopy lens and perhaps look for some more benoxinate. Management would be straightforward if all the clinical signs showed an eye in trouble – obstructed angles, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and glaucomatous disc. But often the situation is much more nuanced. What we often find is only partially obstructed angles, normal pressures, and a healthy-looking nerve.

What do we do now? Do we refer this patient based on a reasonable clinical suspicion to the local DHB eye clinic, which is already heavily burdened; or to a private clinic where the opportunity cost to the patient could be anything from sleepless nights to not being able to afford a long-overdue dental treatment? The critical question is: how safe is it to just watch and monitor? Would it be safer for the patient to receive laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI)?

The Zhongshan Angle Closure (ZAP) trial attempted to quantify the risk of primary angle closure suspects (PACS) developing primary angle closure disease by assessing the efficacy and safety of laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) prophylaxis. The ZAP study’s aims were to determine:

- If prophylactic LPI prevents the development of acute or chronic primary angle closure (PAC) in PACS? (Principal aim)

- The longitudinal changes in angle configuration in the eyes of treated PACS versus untreated eyes

- If the rates of lens opacity and endothelial cell loss in treated and untreated eyes are different?

- The anatomical changes and predictors of angle widening after LPI

- The biometric risk factors of PACS progressing to primary angle closure disease

Table 1. ZAP study design: Randomised control trial

Results

Of the 889 treated and untreated eyes, only 19 treated eyes (2% of study sample or 4.19 per 1,000 eye-years) and 36 control eyes (4% of study sample or 7.97 per 1,000 eye-years) met any of the endpoints by 72 months. This showed a significant protective effect of LPI, with treated eyes having a reduction in the risk of reaching an endpoint (47% reduction in event rate, hazard ratio 0.52, 95% CI 0.30-0.92, p=0.024).

The incidence of angle closure disease was very low among this PACS group. In fact, the trial was extended from the initial 18 months to 72 months in addition to an increased sample size due to smaller than predicted event rate at 18 months. At the end of the 72 months, LPI did have a significant prophylactic effect; however, the benefit was small and most who developed incidence of primary outcomes had no immediate threat to vision.

Table 2. Endpoints (in order of most common to least). NB: Incidence of AAC was too low to show significance and only five untreated eyes developed acute attacks (1.11 per 1,000 eye-years), half of which were because of pupil dilation

The numbers needed to treat (NNT) was 44 to prevent one case of new PAC disease over six years, most of which were non-vision threatening and non-acute. Hence, the authors did not recommend widespread prophylactic LPI for PACS.

LPI’s effectiveness

The ZAP study found that LPI did not cause any major complications and resulted in a marked and immediate increase in angle width in PACS with clear evidence of pupil block. However, after several months, even in eyes that had LPI, the angles narrowed significantly over time. In the untreated eyes, the angle width had a more pronounced decrease compared to the fellow treated eyes.

The study group reported the superior LPI location (between 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock) resulted in significantly greater angle widening compared with temporal or nasal locations. The exact reason behind this anatomical benefit was not found; and further research is needed in this area.

Predictors among eyes which reached endpoints

- Narrower horizontal angle opening distance (measured at 50μm anterior to the scleral spur to the anterior iris surface) on AS-OCT scans

- Flatter iris curvature

- Older age

In summary, anterior segment OCT measurements of biometric parameters describing the angle and iris were predictive of progression from PACS to PAC or acute angle closure. Gonioscopic grades were not associated with progression.

Study weaknesses

The study looked at PACS in Chinese eyes and the outcomes relating to the Chinese population, which lacks generalisability of its findings. Other ethnicities may progress differently and respond differently to treatment. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) scans were not used as a case definition (so there was likely to be an over recruitment of eyes that we wouldn’t consider as PACS if we used AS-OCT, possibly explaining the low frequency of meeting endpoints), nor was it an endpoint in the study. Given most optometrists now have an OCT in their practice, knowing the power of accuracy from the OCT findings and their predictive value would have been very useful.

Implications for personal management

I am better able to inform and discuss with patients the risk of monitoring versus treating PACS. I can say the ZAP study observation showed a very low incidence of non-vision threatening progression among PACS patients diagnosed using gonioscopy, and having LPI lowered that risk further, by half, safely.

I am more comfortable monitoring PACS than I was before, especially in those of Chinese descent. However, every patient and every eye is different and I have seen PACS with very concerning AS-OCT scans, in which case I recommend LPI. In fact, narrow gonioscopy findings should alert optometrists to always perform an AS-OCT, if available, as it can reveal an angle still safely open (monitor) or heading towards trouble (refer). Other asymptomatic patients I would consider offering LPI to would be those who need dilated fundus exams regularly (diabetes and retinal disease), those who have poor access to follow up (rural or overseas deployment) and/or have a positive family history of PACG.

References

- Congdon N, Yan X, Friedman DS, Foster PJ, Van Den Berg TJTP, Peng M, Gangwani R and He M (2012). Visual symptoms and retinal straylight after laser peripheral iridotomy: The ZAP trial. Ophthalmology, 119(7), 1375–1382

- He M, Jiang Y, Huang S, Chang DS, Munoz B, Aung T, Foster PJ and Friedman DS (2019). Laser peripheral iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure: a single-centre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 393(10181), 1609–1618

- Jiang Y, Chang DS, Zhu H, Khawaja AP, Aung T, Huang S, Chen Q, Munoz B, Grossi CM, He M, Friedman DS and Foster PJ (2014). Longitudinal changes of angle configuration in primary angle-closure suspects: The ZAP trial. Ophthalmology, 121(9), 1699–1705

- Jiang Y, Friedman DS, He M, Huang S, Kong X and Foster PJ (2010). Design and methodology of a randomised controlled trial of laser iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure in Southern China: The ZAP trial. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 17(5), 321–332

- Weinreb RN and Moghimi S (2019). Prophylactic laser iridotomy in primary angle-closure suspects. The Lancet, 393(10181), 1572–1574. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33059-9

- Xu BY, Friedman DS, Foster PJ, Jiang Y, Pardeshi AA, Jiang Y, Munoz B, Aung T and He M (2021). Anatomic changes and predictors of angle widening after laser peripheral iridotomy: The ZAP trial. Ophthalmology, 128(8), 1161–1168

- Xu BY, Friedman DS, Foster PJ, Jiang Y, Porporato N, Pardeshi AA, Jiang Y, Munoz B, Aung T and He M (2022). Ocular biometric risk factors for progression of primary angle closure disease: The ZAP trial. Ophthalmology, 129(3), 267–275.

Inhae Park is a glaucoma optometrist working in Wellington Hospital and with Capital Eye Specialists.