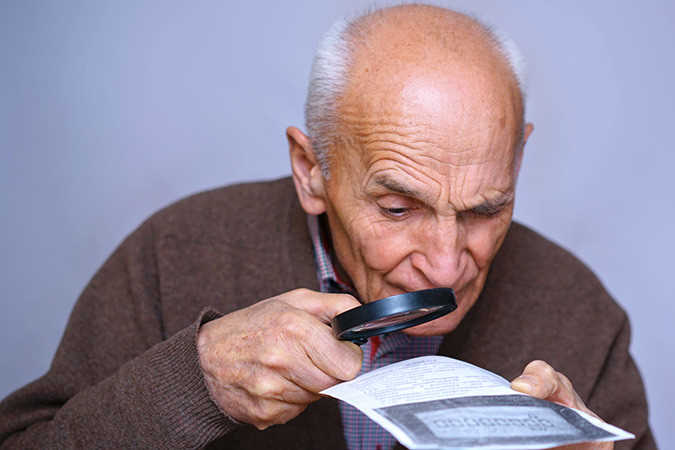

Case study: Loss of vision or something else?

I was contacted by the family of Mr JM, a retired teacher. They were very worried that having always read every newspaper and copy of The New Zealand Listener from cover to cover, as well as having a library of books he was looking forward to getting into, he was now complaining he couldn’t read. This was despite numerous eye clinic appointments, new glasses and various attempts to supply magnifiers and ready-made spectacles. Concerned, they felt his loss of vision was starting to impact his quality of life and he was sinking into depression.

This is not an unusual story for me. I became suspicious when I learnt that apart from bilateral cataract surgery, there was no other ocular history. He had repeatedly been told his eyes were healthy and his vision normal for his age. His general health was also good, according to his daughter, with some hearing loss, which was not a problem as long as he remembered to wear his hearing aids. He often needed reminding as he was “getting a bit forgetful these days”, she said.

The optometrist he’d last seen kindly forwarded his consultation record. Refraction was virtually plano with a +2.50 add and visual acuity of 6/7.5 each eye. The binocular vision was measured (often not done these days, unfortunately) and appeared to be within a normal range. I always request patients bring all their spectacles and magnifiers, whether or not they are using them and, true to form, Mr JM had a bag full of spectacles but said none of them helped.

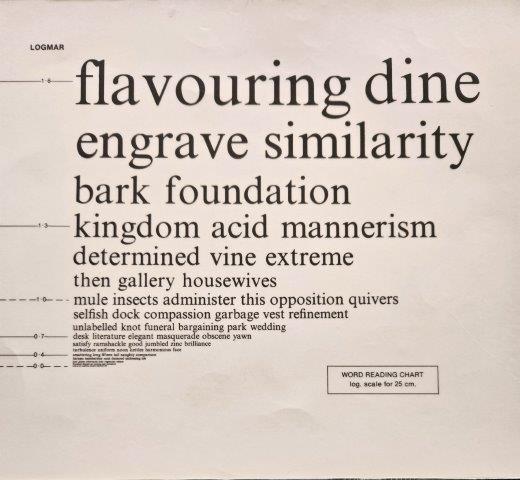

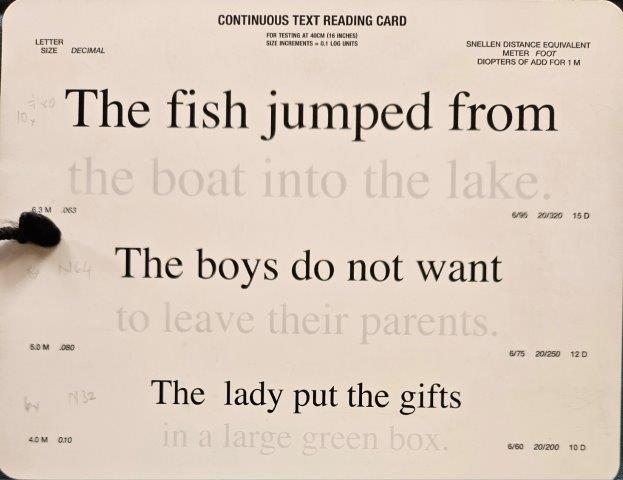

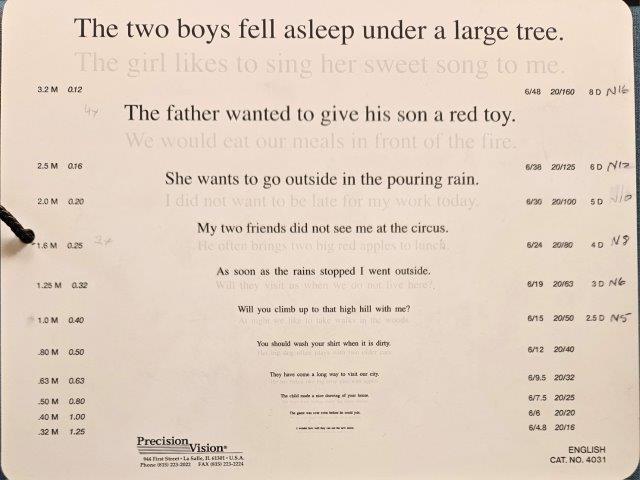

Binocular functional visual fields showed no absolute scotoma or even fading of the red target light, which would impede reading. When I showed him the single-word high-contrast logMAR near chart (Fig 1), he started to pick out odd letters in the top (N 80) line. When I asked him to tell me the word, he continued to pick out letters. I then asked him to tell me the first letter on each line as far down as he could go. He proceeded to do this with apparent confidence. When he got down to the word “then” (N 24) I asked him to read me the whole word. He studied it for a moment and then spelt out the letters. When I asked him what word those letters made, he just shook his head and kept reading the letters down the chart stopping at the N 4 line. I glanced over to his daughter and her expression told me the penny was starting to drop. I was so happy that I had encouraged her to be present at the consultation, as I usually do, and had made the appointment time to suit her. I then swapped to my continuous text chart, which has simple sentences, alternating high- and low-contrast lines1 (Fig 2). He said he couldn’t see it. Switching to a near number chart, Mr JM confidently read the numbers right down to the smallest.

Fig 1. LogMAR random word reading card

Fig 2. Side one and two of the Colenbrander continuous

text high-low contrast reading card

Houston, we have a problem…

“How do I put this tactfully?” I thought to myself. It’s really hard to inform someone that their nearest and dearest probably has dementia, if they haven’t already worked it out for themselves. It’s even harder to tell the patient. I informed Mr JM that he did not appear to have a problem seeing, as he was able to read very small letters and numbers, and I congratulated him on his good vision. I told him that changing his spectacle prescription or using a magnifier was not going to solve the problem, as it was not an optical issue but one of ‘concentration’. (I picked that up from patients admitting to me that they could see but couldn’t concentrate on what they were reading.)

I suggested listening to the radio and audiobooks might be easier for him. Assuming a neurological problem meant his contrast sensitivity would be reduced, I also showed them both how important it is to use good light on anything he wants to see better, including reading, seeing food on his plate or mending things (another hobby he enjoys).

As I departed, I was able to have a quiet word with his daughter, who had already worked out it was his cognition that was failing him (his forgetfulness now looking more like dementia to her too). I reiterated it was not a visual problem and required further assessment by a medical practitioner.

The embuggerance

Although Mr JM was in his seventh decade, there is a form of Alzheimer’s disease which typically presents between 50-60 years of age with a similar history. This is known as posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), made famous by the author Terry Pratchett, who referred to it as “the Embuggerance”. He died from it in 2015, at the age of 67. Life expectancy is 8-12 years from diagnosis.

In PCA, the patient retains a relatively well-preserved memory (compared to other forms of Alzheimer’s), sadly with some insight into what is happening to them, at least in the early stages. This can lead to frustration and anger, which can be directed at the hapless optometrist who ‘can’t get it right’.

You can see the letters; can you tell me what the word is?

A simple question like this can be very revealing. At that moment, you hope there is a family member present to witness the cognitive problem. Trying to always leave on a positive note, I would offer these recommendations:

- Early stages may benefit from advice on increasing light and contrast for all visual tasks

- Audiobooks or technology which scans and converts print to voice bypasses the reading problem

- Home safety advice, as per any low-vision patient: declutter, good light and glare control, increase contrast to improve safety in the kitchen, on stairs, around switches

- Safety around memory loss for switching off appliances, medicines, etc

- Make sure someone else is aware that this appears to be a cognitive problem rather than a visual one

- Report your findings to their GP, suggesting a neurological workup.

Sometimes, if a person hasn’t read for a while they may stumble over words and have difficulty reading fluently. That usually comes back after a bit of practice once they can actually see the words, so it’s good to encourage them to practice reading with their new low-vision aid to build their reading fluency and comfort as soon as possible. I often ‘prescribe’ a minimum of 10 minutes’ reading twice a day for the first week – not too onerous, but enough to get them reading again.

Reference

- Colenbrander mixed contrast reading card. https://www.precision-vision.com/products/vision-testing-aids/acuity-contrast-charts/mixed-contrast-card-in-multiple-languages/

Naomi Meltzer is an experienced optometrist who runs an independent Auckland practice specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.