Pain study restores eyesight, propels new research

Award-winning New Zealand author and low-vision champion Dr Lynley Hood’s eyesight was ‘miraculously’ restored while taking part in a University of Otago study aimed at alleviating chronic pain, resulting in a new investigation to see if more people with low vision can be helped.

“’Miracle’ is not a word we use very often in science, but it was – an accidental miracle,” Dr Divya Adhia, the pain study’s co-lead, told RNZ. Dr Adhia, a post-graduate student with the University of Otago’s School of Physical Education, Sports and Exercise Science, said that while it wasn’t the intended outcome of the study, to see her research make a real impact for people was “miraculous”.

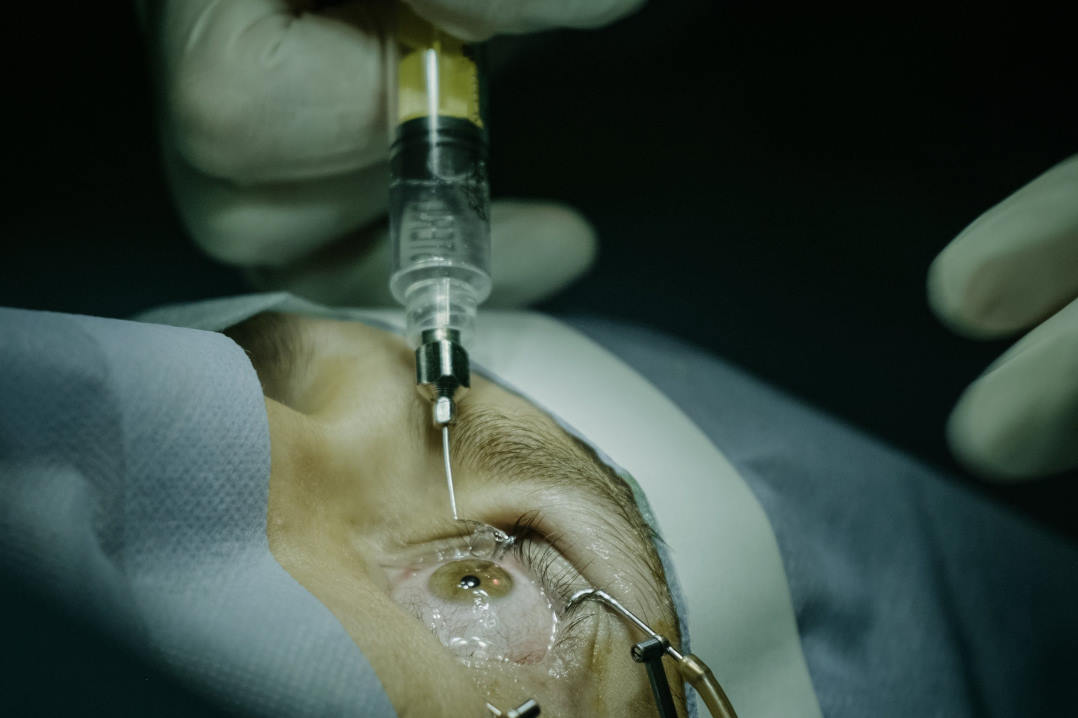

Dunedin-based Dr Hood, who is a trustee of Visual Impairment Charitable Trust Aotearoa (VICTA), has lived with severely reduced vision for more than a decade after developing an acute form of glaucoma. "I lost the central vision in my left eye and it looked like TV static through my right eye.” Her dark adaptation was also incredibly slow, she said, and as it was all deemed permanent, she had no choice but to get on with her life. However, because of her poor vision, Dr Hood suffered a fall in December 2020, causing severe lower-back pain, which was eventually diagnosed as a fractured pelvis. Seeking relief from the pain, she volunteered to take part in the University of Otago’s research project.

The project, co-led by Professor Dirk de Ridder, a scientist with the university’s Brain Health Research Centre, investigated the effects of brain stimulation on chronic pain. As part of the control group, Dr Hood wore a cap wired with electrodes passing electrical current across her scalp. She attended 20 brain-stimulation sessions over four weeks and found that her eyesight steadily improved. “I was startled by the improvement in my vision towards the end of that research, but decided not to tell anyone until my ophthalmologist confirmed it, which he did in July 2022,” she said.

Her retinal specialist, Dr Harry Bradshaw, told Stuff Dr Hood’s visual recovery was not what he’d anticipated. “With the variety of things wrong with her eyes I wasn’t really expecting her vision to ever get better, but against all odds it has.”

The Otago research team said Dr Hood’s improved sight wasn’t caused by the current stimulating her brain, but her eyes. “The equipment they used during the sessions showed the parts of my brain that receive messages from the retina got very excited during the brain research sessions,” said Dr Hood. “Because I was in the placebo group, instead of going into my brain, the current went across my scalp and into my eyes, whereupon the cells in my retina sent excited messages down the optic nerve to the parts of my brain that turn messages from the retina into pictures, colours and words.”

A one-off or a new treatment?

Following her vision recovery, which has remained stable, Dr Hood started researching brain stimulation as a treatment for vision impairment, noting it’s a growing area of research. Locally, news of the unexpected outcome was shared with Dr Alexandra Tickle, commercialisation manager at University of Otago Innovation. The university is now scoping a pilot on brain stimulation for visual disorders, she said. “To explore if this is something we can make accessible to everyone, we first need to understand the potential population that would benefit from this treatment, who would provide the treatment and how we would bring this to market.”

Dr Tickle said her team has engaged the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Otago to establish whether this is a treatment that worked exclusively for Dr Hood or whether others could benefit from it too. Dr Kelechi Ogbuehi, senior lecturer in ophthalmology, is driving the vision part of the pilot.

The uncertainty of Dr Hood’s original diagnosis is a challenge, said Dr Ogbuehi. “We are still not sure what Lynley’s diagnosis was. Several specialists diagnosed her with possible glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa, acute zonal occult outer retinopathy… though now the consensus is gathering around retinitis pigmentosa.” These diseases are all varied in their pathophysiology and the chances of repeating the success will depend on what eye disease, or combination of eye diseases, Dr Hood has, he said. “Whatever the case, what we are dealing with here is a conduction problem.” Patients with diseases that ‘kill’ the individual fibres that make up the optic nerve, such as glaucoma, will be much less likely to benefit from the trial, he explained. “Whereas diseases that leave them more or less intact but perhaps misfiring just might be helped.”

For the pilot, several measurements are required: visual acuity, electroretinogram, optical coherence tomography, visual fields and dark adaptation, said Dr Ogbuehi. “We have all the equipment we need except for perhaps the most important test – dark adaptation. For that, I would like to purchase the MonColor ganzfeld visual stimulator from Metrovision and the AdaptDx Pro from MacuLogix.”

Dr Hood said she thinks brain stimulation is the most likely explanation of her vision recovery and is pleased about the follow-up research currently underway. “I’m on a mission to correct people when they say it’s a miracle – it’s obviously science.”