Sarcoidosis and the eye

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory condition characterised by non-caseating granulomas. It is a leading cause of inflammatory eye disease. Although the exact aetiology is unknown, sarcoidosis is likely due to abnormal immune responses to environmental antigens in genetically susceptible individuals1. It most commonly presents at age 20-30 or 50-60 years and, in New Zealand, may be more common in Pasifika or subjects with Scandinavian ancestry.

Many organ systems can be affected by sarcoidosis, most frequently the lymphatic system, lungs, skin and eyes, with 30-50% of cases diagnosed from abnormal chest x-rays performed for other reasons. One-third also have non-specific fever symptoms, weakness and weight loss2. Ocular involvement occurs in up to 80% of individuals3 and ocular manifestations can be the presenting feature prior to an underlying systemic diagnosis.

Ocular sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis can affect all parts of the eye. The most common manifestations are uveitis, dry eye and conjunctival nodules4. Ocular involvement is the presenting feature in approximately 20-30% of subjects, prior to a systemic diagnosis4.

Adnexa and orbit

Adnexal involvement includes eyelid granulomas (Fig 1), madarosis, poliosis, entropion and trichiasis4. Lagophthalmos can also occur if associated with facial nerve palsy4. Lacrimal gland granulomas can present as dacryoadenitis and keratoconjunctivitis sicca4. Orbital involvement can also cause proptosis and nasolacrimal duct obstruction4. Myositis causes ocular motility deficits that can mimic thyroid eye disease1.

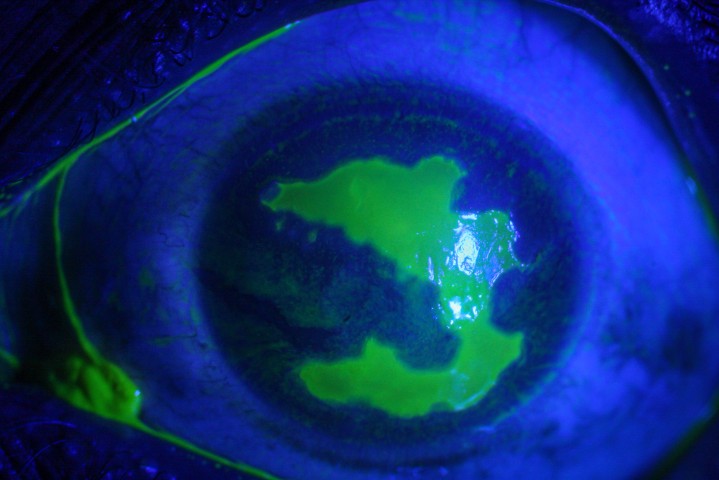

Ocular surface

Conjunctival granulomas can occur in up to 40% of cases but may be missed as the patient tends to be asymptomatic4. Extensive conjunctival involvement can cause diplopia and dry eye1. Sarcoidosis can cause cicatrising conjunctivitis4. Corneal involvement can lead to peripheral ulcerative keratitis and interstitial keratitis4. Band keratopathy can develop secondary to chronic sarcoid uveitis1.

Uveitis

Uveitis is a common and important vision-threatening manifestation, occurring in 30-70% of individuals with sarcoidosis4. Although sarcoidosis has been shown to be more likely in men, females seem more prone to uveitis5. Sarcoid uveitis is usually bilateral and tends to follow a chronic course4. Scleritis and episcleritis can also occur. Uveitis develops early in sarcoidosis, usually within one year of systemic diagnosis1.

Posterior uveitis is most common, followed by panuveitis then anterior uveitis and intermediate uveitis. Uveitis is classically granulomatous with ‘mutton-fat’ keratic precipitates (Fig 2A) and iris granulomas (Fig 2B). Snowballs, snowbanking and ‘string of pearls’ can occur with intermediate uveitis. Retinal involvement includes periphlebitis – which, when extensive, appears as ‘candle-wax drippings’ (Fig 2C) – macroaneurysms and multifocal choroiditis (Fig 2D). Granulomas can involve the optic nerve and choroid.

Fig 2. Granulomatous 'mutton-fat' keratic precipitates (A), Koeppe iris nodules along the pupillary border (B - arrows), periphlebitis with “candle-wax dripping” appearance (C) and atrophic multifocal choroiditis (D)

Neuro-ophthalmology

Neurologic involvement occurs in 5-26% of cases and includes papillitis, papilloedema, granuloma, compressive or infiltrative optic neuropathy and optic atrophy, abnormal pupillary responses and ocular motility abnormalities4. Facial nerve palsy is the most common neuro-ophthalmic manifestation but is usually self-limited1.

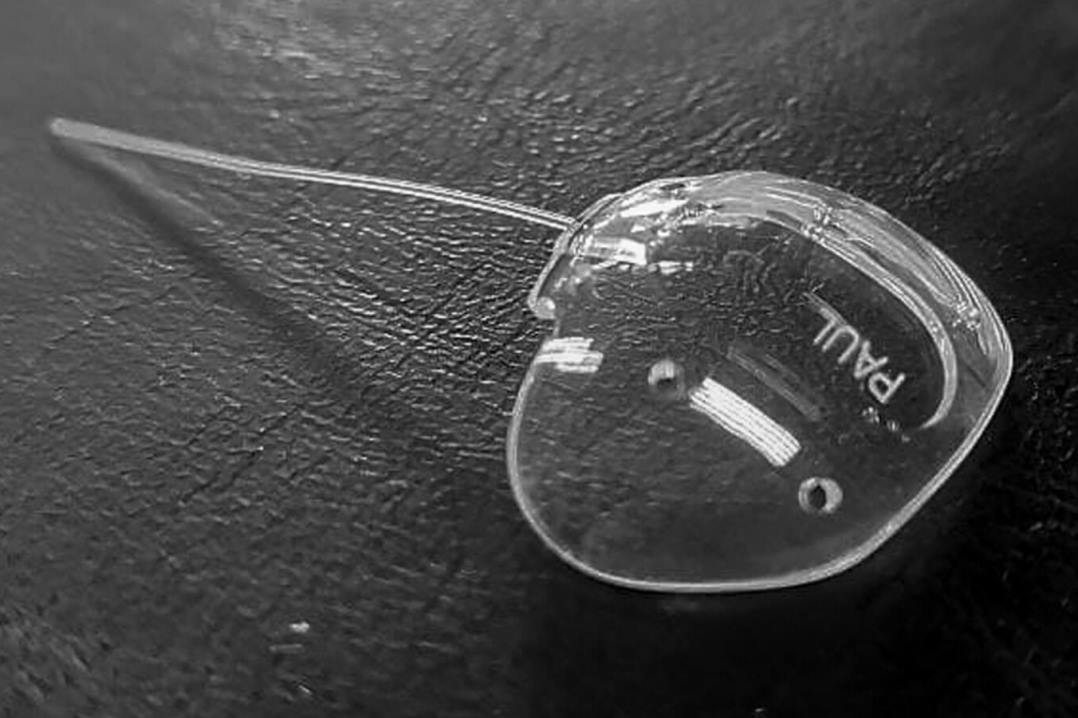

Glaucomatous optic neuropathy can occur either secondary to uveitis or to trabecular meshwork nodules. Trabecular nodules and tent-like peripheral anterior synechiae are seen in over 50% of subjects with systemic sarcoidosis4 and glaucoma is more common in those with angle signs6. Ocular hypertension and glaucoma can also develop as a result of sarcoid orbital masses or secondary to corticosteroid therapy4.

Ocular sarcoidosis (IWOS) criteria

A diagnosis can be difficult to make and requires clinical suspicion and supportive investigations. The International workshop on ocular sarcoidosis (IWOS) devised diagnostic criteria for ocular sarcoidosis in 2009, with revisions in 20197. This consisted of seven clinical signs and five investigation criteria:

IWOS revised criteria 2019: clinical signs

- Mutton-fat keratic precipitates, iris nodules

- Trabecular meshwork nodules, tent-shaped peripheral anterior synechiae

- Vitreous opacities – snowballs, string of pearls

- Multiple chorioretinal peripheral lesions (active and/or atrophic)

- Nodular and/or segmental periphlebitis (+/- candlewax drippings) +/- retinal macroaneurysm in inflammed eye

- Optic disc nodules/granuloma and/or solitary choroidal nodule

- Bilaterality

IWOS revised criteria 2019: investigations

- Negative tuberculin skin test in BCG-vaccinated patient or previous positive

- Elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (sACE) and/or lysozyme

- Chest x-ray showing bilateral hilar (bihilar) lymphadenopathy

- Lymphopenia

- Chest CT scan in patients with a negative chest x-ray results

Four diagnostic levels for ocular sarcoidosis were defined by IWOS: definite, presumed, probable and possible. Definite ocular sarcoidosis is defined as a biopsy-supported diagnosis in the presence of compatible uveitis. Presumed ocular sarcoidosis consists of a chest x-ray showing bihilar lymphadenopathy in the presence of compatible uveitis, without biopsy confirmation. In cases where a biopsy has not been performed and the chest x-ray does not show bihilar lymphadenopathy the presence of at least three intraocular signs and at least two positive laboratory tests is consistent with probable ocular sarcoidosis. At least four signs and at least two positive laboratory tests in the presence of a negative lung biopsy define possible ocular sarcoidosis.

Ocular investigations

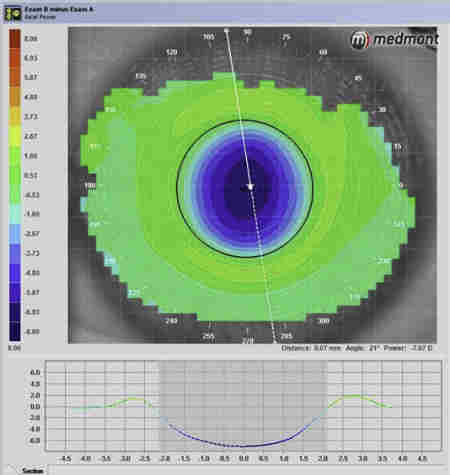

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

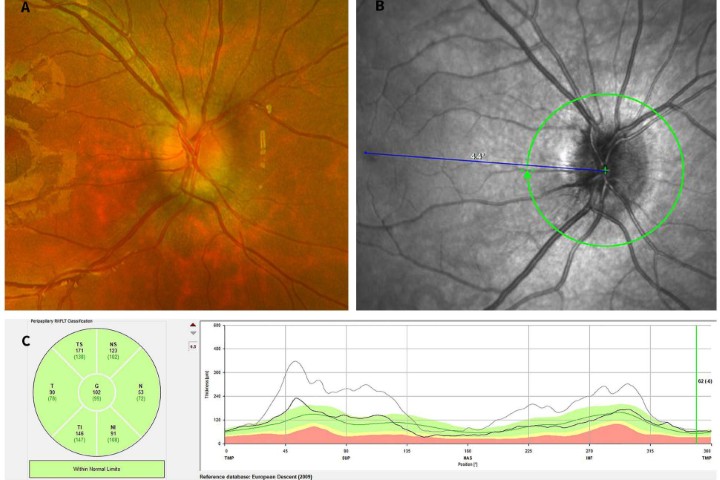

OCT is a non-invasive tool that is readily available in clinic and can assist in diagnosis and monitoring of ocular sarcoidosis. Macular oedema secondary to sarcoid uveitis can be monitored and the integrity of the photoreceptor inner and outer segment junction and external limiting membrane can be predictive of functional outcome. Additionally, enhanced-depth OCT can be used to visualise choroidal granulomas and their response to treatment (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Enhanced depth OCT using Heidelberg HRA Spectralis OCT demonstrating choroidal granuloma (arrow)

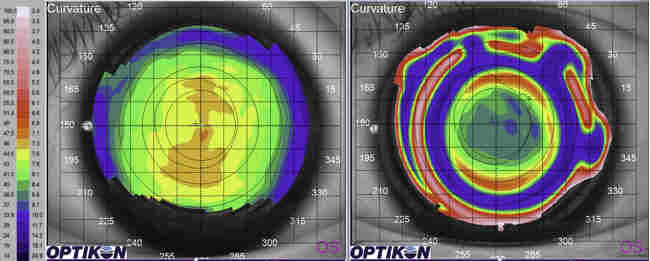

- Fundus fluorescein and ICG angiography

Fluorescein angiography demonstrates periphlebitis and secondary uveitic complications including cystoid macular oedema, retinal neovascularisation and choroidal neovascular membranes.

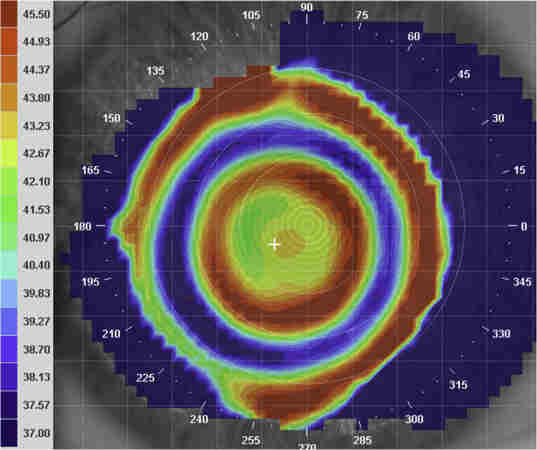

Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography can demonstrate choroidal granulomas which are hypocyanescent (Fig 4) and may be more extensive than apparent on clinical examination. ICG angiography also demonstrates uveitic complications of choroidal neovascular membranes and retinal neovascularisation.

Fig 4. Multifocal hypocyanescent choroidal granulomas on ICG angiography

Systemic investigations

There is no stand-alone diagnostic serologic or radiologic test for sarcoidosis and each test carries differing sensitivity and specificity for sarcoidosis (Table 1)8. Diagnosis is based on a consistent clinical and radiologic presentation in conjunction with histopathologic evidence of non-caseating granulomas where a tissue biopsy is possible, following exclusion of other granulomatous disease.

Table 1. Reliabilty of screening investigations, taken from Niederer and Sims

- Blood Tests

sACE is frequently elevated. As well as in diagnosis sACE can be used to measure disease activity in systemic sarcoidosis and is reflective of granuloma load9. sACE has a high negative predictive value of 97.0%; in subjects with a normal sACE further screening is not necessary unless there is a high degree of clinical suspicion8. It is, however, important to remember that sACE can be falsely lowered in those taking ACE inhibitors8.

Significant lymphopenia is an independent predictor of sarcoidosis in those presenting with uveitis. Lymphopenia replaced abnormal liver function tests in the updated 2019 IWOS criteria7.

- Radiologic Testing

Bihilar lymphadenopathy is frequently observed in sarcoidosis (Fig 5). The sensitivity and specificity for CT is 98.0% and 100% and for chest x-ray 57.6% and 100%. Although CT imaging has a higher sensitivity and specificity, CT imaging must be balanced with radiation exposure and investigative costs. Chest x-ray is a good primary screening tool and CT should be reserved for those with abnormal x-ray findings and in highly suspicious cases8.

Fig 5. Chest x-ray demonstrating bihilar lymphadenopathy

- Histopathology

Histopathologic confirmation of non-caseating granulomas is diagnostic of sarcoidosis but not always possible. Tissue biopsy can be obtained from affected lung, skin, conjunctiva, lacrimal gland and lymph nodes. Arbitrary biopsy of unaffected tissue has low positivity rates1 and is not recommended due to low yield.

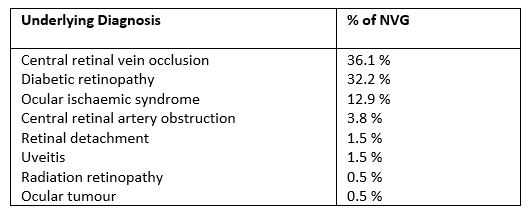

Systemic associations

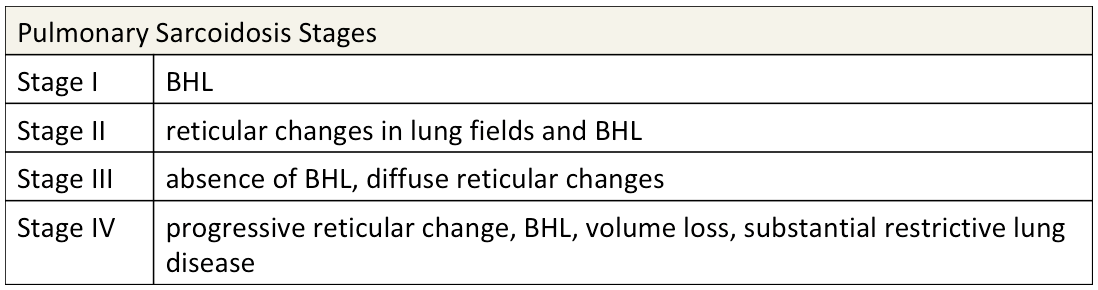

- Pulmonary sarcoidosis

Intrathoracic involvement is the hallmark of the disease, present in over 90% of sarcoidosis patients10. Presentation can vary from asymptomatic through to severe pulmonary fibrosis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pulmonary sarcoidosis is subdivided into four stages based on severity (Table 2).

Table 2. Four stages of pulmonary sarcoidosis (BHL=bihilar lymphadenopathy)

- Cardiac sarcoidosis

Cardiac sarcoidosis is difficult to diagnose and affects about 5% of subjects clinically, while autopsy studies show up to 25% of those with systemic sarcoidosis have cardiac involvement11. Cardiac manifestations include arrhythmia, high grade atrioventricular block and heart failure. Importantly, it is a cause of sudden death due to brady- and tachyarrhythmias.

Chorioretinal lesions have been shown to be a marker of microcirculatory damage in sarcoidosis. Subjects with choroidal involvement are at increased risk of cardiac involvement3.

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis

Cutaneous involvement occurs in a third10 of subjects with systemic sarcoidosis and is subdivided into sarcoidosis-specific skin lesion characterised by non-caseating granuloma and non-specific lesions including erythema nodosum. Non-caseating granulomatous reactions related to sarcoidosis can also occur within tattoos in which the tattoo pigment acts as a nidus for granuloma formation (Fig 6).

Fig 6. Sarcoid granulomas associated with red tattoo ink

- Musculoskeletal sarcoidosis

Arthropathy occurs in 5-15% of cases10. Erythema nodosum accompanies arthritis in 25-30% of cases10. Enthesitis has been reported at a prevalence of 5-8% with Achilles tendinitis being most common10.

- Hepatic sarcoidosis

The majority of patients with isolated hepatic sarcoidosis are asymptomatic, but granulomas have been found in 75% of subjects on fine needle biopsy6.

- Renal sarcoidosis

Renal involvement is usually subclinical. It has been reported in 3% of patients clinically, manifesting as granulomatous interstitial nephritis, but has been found in up to 20% of autopsy studies10.

- Gastrointestinal tract sarcoidosis

Gastrointestinal tract sarcoidosis is rare, occurring in less than 1%10 of cases and can present with non-specific symptoms of epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and weight loss. It is characterised by granulomatous infiltration in the mucosa and muscular layer, leading to mucositis, ulcer, obstruction and stricture formation.

Treatment

In some cases, systemic sarcoidosis is a self-remitting disease that does not require treatment. However, 10-30% of patients will develop chronic or progressive disease requiring systemic treatment. Treatment is required for life-threatening organ involvement such as advanced pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension and central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Treatment is also recommended for organ involvement that can lead to functional impairment, including posterior- and panuveitis.

Corticosteroids are the mainstay treatment of sarcoidosis, with a response to steroid obtained in 80-90% of cases12.

Approximately 15% of subjects will require second-line immunosuppression. Traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate, mycophenolate and azathioprine are used as second-line agents: when corticosteroids are contraindicated; if the disease is refractory to corticosteroid; those with difficulty tapering corticosteroid to <7.5-10mg; or in cardiac sarcoidosis or neurosarcoidosis.

Prognosis

Systemically, ethnicity (especially African-American and Afro-Caribbean origins), age above 40 at presentation, lupus pernio, chronic uveitis, sinonasal and osseous localisation, CNS involvement, cardiac involvement, severe hypercalcemia, nephrocalcinosis and radiographic pulmonary stages III and IV have been associated with poorer overall prognosis12.

The visual prognosis is generally favourable for subjects with ocular sarcoidosis. Sarcoid uveitis has a better prognosis than other causes of noninfectious uveitis with subjects retaining good vision over a 10-year period6. However, vision loss occurs in about 11% of subjects with sarcoid uveitis6. Posterior- and panuveitis in particular have the poorest prognosis due to complications of choroidal neovascular membranes, retinal neovascularisation, subretinal fibrosis and optic atrophy. Glaucoma is more likely in sarcoid uveitis compared to other forms of non-infectious uveitis6. About 20% will develop glaucoma, which is also associated with increased risk of vision loss6.

Poorer visual prognosis has been observed in those with advanced age, Black ethnicity, female gender, chronic systemic disease, posterior segment involvement, delayed management by over one year, poor initial visual acuity, peripheral retinal lesions and presence of complications of cystoid macular oedema and glaucoma2. The severity of macular oedema correlates with severity of ocular inflammation and loss of visual acuity. The presence of retinal periphelbitis, optic disc or choroidal granuloma, retinal detachment, epiretinal membrane and glaucoma are associated with increased risk of vision loss6.

In conclusion

Sarcoidosis is an important cause of ocular inflammation that can occur in isolation or with other organ involvement. The prognosis is variable but often has a good response to corticosteroid therapy. Severe cases require systemic immunosuppression. The ocular course can be complicated by cataract, glaucoma, cystoid macular oedema, subretinal fibrosis and retinal neovascularisation.

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary to manage these individuals and it is important to involve a pulmonologist and cardiologist.

References

- Rothova A. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(1):110-6

- Salah S, Abad S, Monnet D, et al. Sarcoidosis. J Fr Ophthalmol. 2018;41(10):e451-e67

- Yang S, Salek S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular Sarcoidosis: new diagnostic modalities and treatment. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2017;23(5):458-67

- Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum RT. Ocular Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):669-83

- Birnbaum AD, French DD, Mirsaeidi M, Wehrli S. Sarcoidosis in the national veteran population: association of ocular inflammation and mortality. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(5):934-938

- Niederer RL, Sharief L, Lightman SL, Tomkins-Netzer O. Uveitis in sarcoidosis - clinical features and comparison with other noninfectious uveitis. Ocular Immunol Inflamm In press. 2021

- Mochizuki M, Smith JR, Takase H, et al. Revised criteria of International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(10):1418-22

- Niederer RL, Sims J. Utility of Screening Investigations for Systemic Sarcoidosis in Undifferentiated Uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;206:149-53

- Niederer RL, Al-Janabi A, Lightman SL, et al. Serum Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Has a High Negative Predictive Value in the Investigation for Systemic Sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;194:82-7

- Ungprasert P, Ryu JH, Matteson EL. Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Sarcoidosis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual. 2019;3(3):358-75

- Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation. 1978 Dec; 58(6):1204-11

- Jammal TE, Jamilloux Y, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Valeyre D, Seve P. Refractory Sarcoidosis: A Review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:323-45.

Dr Priya Samalia is a medical retina fellow working at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. She undertook her RANZCO registrar training in New Zealand and completed a uveitis fellowship at Greenlane Clinical Centre in Auckland, New Zealand in 2020.

Dr Rachael Niederer is a clinician-scientist working at Greenlane Clinical Centre, the University of Auckland and Auckland Eye. She completed her PhD at Auckland University and fellowship training in uveitis and medical retina at Moorfields Eye Hospital, London. She is the author of 75 peer-reviewed publications and has been the recipient of several awards, including the Howsam Medal for excellence in ophthalmology, the Vice chancellor best-doctoral thesis award and the Sir William McKenzie prize in ophthalmology.