Genes and gems with Retina Specialists

Retina Specialists’ winter educational evening for optometrists had both genes and gems on the menu.

Associate Professor Andrea Vincent kicked the evening off with a story fit to tug the heart strings. It concerned a two-year-old boy from Christchurch with suspected early onset Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a group of inherited retinal diseases characterised by severely impaired vision or blindness, typically presenting between birth and five years of age. The condition causes degeneration and/or dysfunction of photoreceptors and, in some cases, other body organs, such as kidneys, may become affected. There are many gene mutations associated with LCA, including RPE65 and AIPL1, and this boy had two mutations in AIPL1.

At the time of referral, no measure of vision could be obtained, but the prognosis was that because he had two mutations of the gene he would generally have few photoreceptors left by the time he was five. In effect, left untreated, he would have had no useable vision by the time he started school.

Stuart and Carolyn Campbell

The boy appeared to be 4–5 dioptres hypermetropic and rubbed or poked his eyes a lot, which is typical of children with LCA and can potentially cause associated corneal and other ocular damage. In December 2017, Spark Therapeutics obtained FDA approval for Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec), a gene therapy which has improved vision in children and young adults with the RPE65 mutation. The adenovirus-mediated gene augmentation therapy is injected under the retina. Cells with the non-functioning gene are invaded by a functioning gene that replaces the non-functioning gene to make the cell function normally. Of course, that is only viable while there are still functioning photoreceptors to work with, which means time is of the essence.

There are thought to be only three patients in New Zealand with this genetic variant but, at the time of writing, Pharmac is still reviewing the application for the $700,000 per eye Luxturna treatment. However this child had LCA associated with the AIPL1 gene, so Luxturna was not the right treatment, even if it was funded. Fortunately A/Prof Vincent was aware that Moorfields had developed a gene therapy for AIPL1 and had treated one eye in each of four children with this rare disease with this new gene therapy drug which has been approved by the European Medical Agency (EMA) for compassionate use. Moorfields agreed to treat this boy. The family had to pay for travel costs to the UK and for some hospital procedures, but not for the treatment drug itself. Four months later, the boy’s vision in his treated right eye was 25% better than before treatment. On 6 June this year, the second eye was treated. The child appears to be favouring the right eye, so some amblyopia is likely from the delay in treating the left eye, but he is making progress, indicating he appears to have some photoreceptors still working. OCT showed a thin layer of residual photoreceptors.

The parents, however, need answers quickly, said A/Prof Vincent. They want to know if he will go blind and whether other members of the family will develop it or potentially be born with the same genetic issue. Can anything be done to slow down the process and what decisions do they need to make, in terms of the child’s educational pathways? Clinicians also need to know what else might be happening in this child’s body that may be associated with the retinal changes.

When a child presents with unexplained loss of vision, the search for inherited disorders begins. Many countries do not have access to genetic testing and, in a small country such as New Zealand, the numbers of cases with such rare genetic disorders can be infinitesimal, which not only emphasises the need for geneticists such as A/Prof Vincent to have international connections, but also to have the tools to make a timely diagnosis.

Anh Dao Le, Alice Ku and Kathreena Lim

A/Prof Vincent explained that even when she gets a referral with a diagnosis, she prefers to start with a blank sheet and not assume anything, otherwise she can be led down the wrong path with an unconscious bias. The starting point is always to look at the rest of the family; however, this information may be patchy. Autofluorescence helps a lot, as it gives much more detail of the changes occurring at the macula, she said.

Asked how long the treatment will last, she replied, “How long is a piece of string? We just don’t know because we only have approximately seven years of data.” Hopefully, we will get an answer in future educational evenings. Watch this space!

Watch and learn

Dr Rachel Barnes continued with some interactive case studies for those who like to test their IT skills at the same time as their optometric knowledge.

Her case concerned a 26-year-old who presented with sudden vision loss in one eye after a two-week history of mild upper respiratory infection. OCT showed a big central cyst within the bacillary layer of the retina (Fig 1). This is typical of acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE), a form of cystic retinal oedema. Usually bilateral, it mostly appears in a person’s second to fourth decade, often after a virus and, importantly, may be associated with cerebral vasculitis.

A bacillary layer detachment (a term coined as recently as 2018) is separation of the bacillary layer of the retina due to a relative weakness in the myeloid layer. There is a breakdown of the retinal pigment epithelium blood retina barrier while the external limiting membrane is preserved, allowing fluid to get into the intra-retinal space. The fluid can often look quite turbid.

Fig 1. Bacillary layer detachment. A retinal cyst usually resolves in 4–8 weeks, but steroids may hasten the process

The one that nearly got away!

The next case history was about a middle-aged male who’d had a routine normal dilated examination one year before presenting for his annual examination related to a history of rheumatoid arthritis.

On this occasion he reported recently attending an A&E clinic for vague discomfort and blur in one eye. He was given ocular lubricants, which appeared to resolve the issue, though not entirely.

Richard Chinn, John Adam and Dennis Oliver

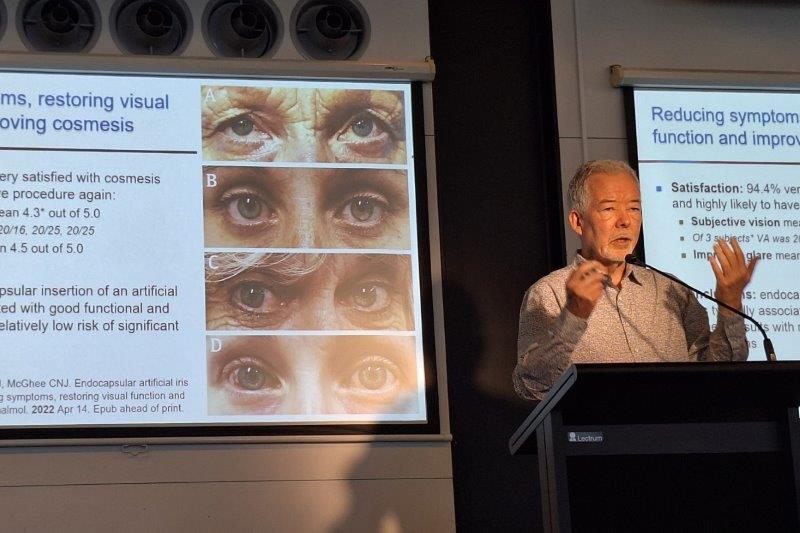

Dr Barnes noted what appeared to be a group of inferiorly located dilated episcleral vessels that could be taken for mild blepharitis, possible episcleritis or even an odd-appearing early pterygium. Dilation revealed what was lurking below the surface: dilated sentinel episcleral vessels were disproportionately dilated, with tortuous episcleral blood vessels, which provided a clue for the presence of an underlying asymptomatic occult ciliary body melanoma.

Dr Barnes confessed her blood runs cold every time she looks at the slide of ‘the one that nearly got away’.

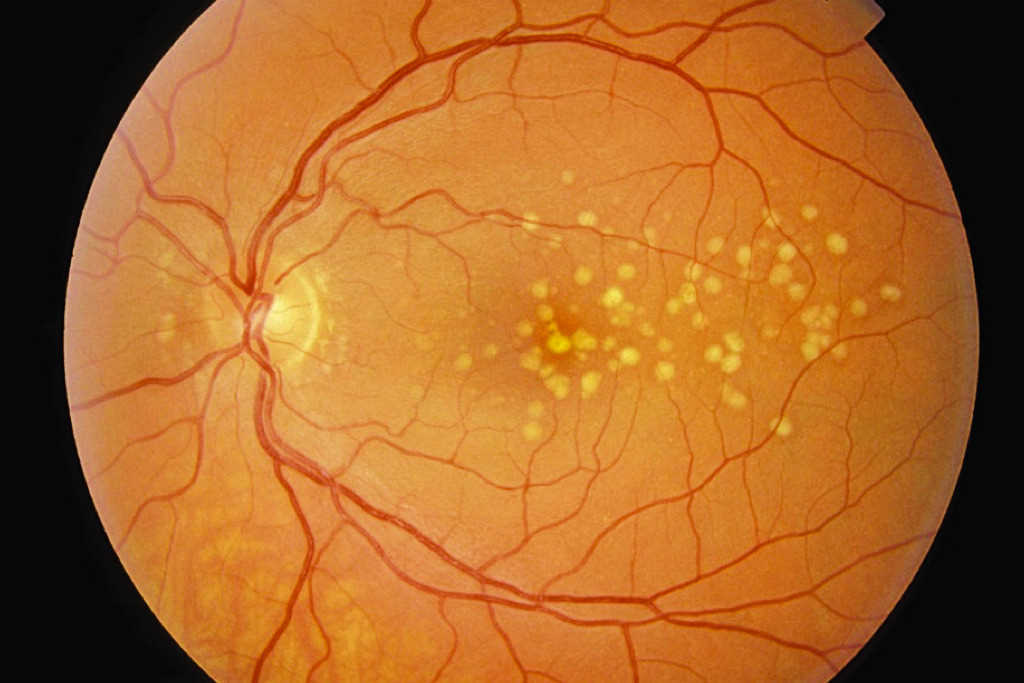

Assessment and treatment of geographic atrophy

Dr Leo Sheck advocated the use of autofluorescence as the best imaging modality for assessing geographic atrophy (GA). His experience with the use of C3 (Syfovre) and C5 (Izervay) inhibitors, which are FDA- (but not yet Medsafe-) approved treatments for GA, is that there are practical problems, quite apart from the expense (self-funding at approximately $3,000 per injection, plus transportation from the US).

Tiffany Ong and Eva Woodward

One problem is deciding when to start treatment. It is also very difficult to track effectiveness, since there is no obvious change in fundus appearance or vision. A pathway for assessment of functional change is by doing microperimetry, which is available through the University of Auckland.

The treatment is also not without risk of infection and potential neovascular transformation, said Dr Sheck. Ultimately, the best outcome at this stage is that progression of GA is slowed. It’s certainly a hard sell for the average patient with GA, even if they have deep pockets! There is a strong case for the ‘wait and see’ approach, unless there is an urgent reason to take the deep dive.

However, there is a route to apply for continued treatments for patients who have already started treatment overseas. If they need treatment and are well informed, the drug can be accessed. Patients who have GA and have previously been treated for neovascular maculopathy are, at present, excluded from trials. It’s good to know that progress is being made.

Naomi Meltzer is an optometrist who runs an independent practice specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.